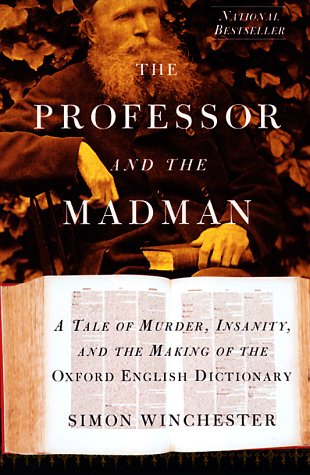

The Professor and the Madman

Marshall Tankersley, Student Editor

In his book The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (1998), Simon Winchester chronicles the history of the insane William Chester Minor and discusses why his contributions were so valuable to James Murray, the long-serving editor of the OED. Winchester calls his account of the story of Doctor Minor a tale of murder, insanity, and ‘redemption.’

Christians understand redemption as an action where God saves us from the consequences of our mistakes and sinfulness; in its financial context, the word means ‘to clear a debt.’ So how is the tale of Doctor Minor a story of redemption?

The tale of Doctor W. C. Minor, late of the United States Army, is one which would seem to shed no light. Doctor Minor’s life and gradual descent into schizophrenic insanity is a dark tale, and one could be forgiven for assuming that there is not restoration at hand for such a troubled soul. He murdered a man in cold blood, and was sent away for such a heinous crime. What else is there to understand?

However, Christians must never be so quick to abandon anyone, certainly not least of all because we were ourselves not abandoned. Doctor Minor’s life entered hell, yes, but that entrance was not final. Through the work of the OED, Minor finally felt that he was able to return to the land of the living, to contribute back to society and not remain cast out by the vices of his feverish mind. Doctor Minor experienced redemption.

When one learns that Minor was a murderer, one feels a sort of righteous indignation. Of course he deserved what he got; he killed a man! But this is only half the story, and Christians should not be so quick to judge until the entirety is understood. Yes, Minor killed a man. But that act of murder was not necessarily intentional, nor was it what Minor in the truest sense necessarily wanted. Beset by all manner of mental demons, Minor’s actions were at best classified as taken under an influence, and even then not an influence Minor himself chose. His deranged mind convinced him that the man he had killed was an invader of his own privacy and out to harm Minor, so the Doctor killed him in what he believed to be a measure of self defense. This does not justify the murder, of course, but it does make one sympathize with the Doctor.

Perhaps the best example of how Minor later felt regret and remorse for his flawed actions can be understood when Winchester tells how Minor wrote to the widow of the murdered man.

He explained to Eliza Merrett how immeasurably sorry he was for what he had done, and he offered to try and help in any way he could – perhaps by settling money on her or her children. (126)

Doctor Minor not only expressed his remorse for his actions to the bereaved widow, but he also offered to do what he could to make things right and to provide for them what the man taken from them would have done.

Still, shut up in Broadmoor Prison away from society, Doctor Minor felt secluded and alone. To an extent, he felt what Hell must feel like, as (aside from temporary visits from Mrs. Merrett and his distractions of music, painting, and books) he was cut off from every good thing he had ever known in his life. Then a light dawned – in one of the books Mrs. Merrett had brought him, he discovered one of James Murray’s pleas for assistance on the OED. Finally, he had discovered something to which he could devote himself, and something which would benefit his fellow man. Doctor Minor set about work with an intensity unmatched by almost any other OED contributor, making his entries as perfect as they could be and as many as possible. He made himself the indispensable contributor that James Murray never knew he needed, with definition after definition made available to the editors of the Dictionary when they required specific help.

Then came the day when Murray realized what Minor was.

Minor had never disclosed his true nature to Murray or the other contributors of the OED, and now that he had, how would they react? Would Murray cast him aside to the dregs of society as so many others had done? Would Minor again have no hope?

The answer from Murray was a resounding no. The Christian character of the Scottish-born lexicographer showed through, and he stood by Minor’s side more and more after he learned of his ailments. Murray refused to lose hope in the sick American, and did his best to stand with him and for him when the need arose.

Murray visited Minor when he was feeling down and consolable, but cared enough for him to know not to visit when the American Doctor was gloomy but unable to be consoled. Murray cared for Minor more than a valuable contributor to a great project; he cared for him as a fellow human being and embodied Christ’s character. When Minor was mistreated, Murray and his wife were staunch in their attempts to allow him to return home where he could be better cared for. Murray showed Minor that he need not remain in his own private Hell; rather, he could and was redeemed. In an even more Christian fashion, this redemption and reconnection with humanity came not through his works as a lexicographer, but through the intervention of Murray. The work on the dictionary merely brought the fellow to the Scotsman’s attention.

Winchester’s story of Minor’s path to redemption should be inspiring to all Christians, as it shows not just that Minor could be redeemed or even that he was, but it shows off how true Christian character (as exemplified by Murray) can be used by God to do so. Minor, though he struggled with his mental problems for the rest of his life, still knew that he was not a cast-off, that he was not meaningless, and most importantly, that he was loved.