C.S. Lewis and Ways of Writing

Jessica Mau

In his essay “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” C.S. Lewis explains the ways books are written for young readers. Two of the examples that Lewis provides are good ones, while the other he provides is not.

The bad example is simply writing what children want (or what the author thinks they want), with nothing beneficial added to it. For example, a book could be written about a genie who can grant every wish and send the child protagonist on crazy adventures through make-believe lands with no consequences. Such narrative wish-fulfillment might appeal to some children, but in the process of writing such a story the author would sacrifice the chance to give them a more meaningful and perhaps beneficial experience.

Lewis provides a good way to write a children’s story that is somewhat similar to his bad example in that the author gives children the story they want, but there is one important difference: the author narrates it as if the story is being told aloud to a child in person. Many stories for children, such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, begin as stories told aloud to actual children. Lewis argues that this method of storytelling saves the author from trying to tell a story to children for which the author has no interest in, but is merely checking off boxes of what he or she believes children like to hear. Lewis is confident that children will notice such a flaw and call the author out on it. Therefore, by addressing his or her story to a specific child audience, the story will avoid some of these pitfalls and will make the author more invested in it.

The last method for writing a children’s story that Lewis provides is the one he personally uses—simply writing a children’s story since it is the best medium for what he has to say.

The third way, which is the only one I could ever use myself, consists in writing a children’s story because a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say: just as a composer might write a Dead March not because there was a public funeral in view but because certain musical ideas that had occurred to him went best into that form. (Lewis 23)

Lewis points out the irony that sometimes a book is written with no intention of it being for children, and it just happens to be children like to read it more than adults do.

Lewis also makes an interesting argument for adults reading “children’s” literature. He argues that society treats the term “adult” as a form of approval when it shouldn’t be. Ironically, since everyone is so concerned in being adult-like, they become childish in the way that they are embarrassed at even the thought of being childish or not completely grown up. Part of becoming an adult is not being afraid of being considered childish, as Lewis says in his famous quote:

Critics who treat adult as a term of approval, instead of as a merely descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown up because it is grown up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these things are the marks of childhood and adolescence. And in childhood and adolescence they are, in moderation, healthy symptoms. Young things ought to want to grow. But to carry on into middle life or even into early manhood this concern about being adult is a mark of really arrested development. When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up. (Lewis 25)

Lewis talks about how our culture has a twisted view of growth, encouraging us to drop the old things to get the new. This is a very shallow and superficial notion of what maturity means because in life it is quite practical to add onto the old things rather than discard them. Lewis mentions that the world views growth is mere evolving, or exchanging one thing for another. However, real growth is more complicated and involves constant retrospection and evaluation.

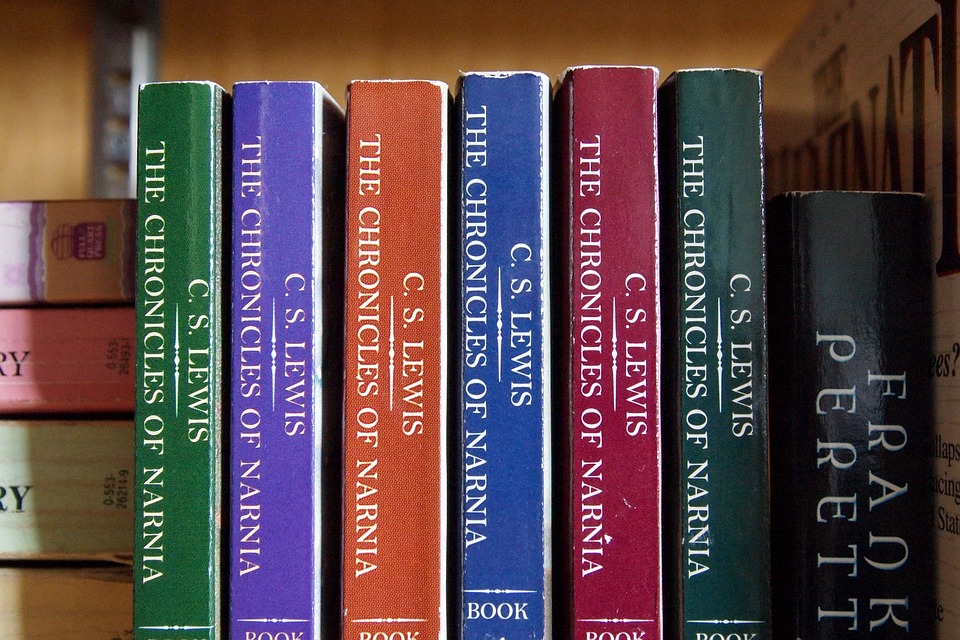

I found the idea of keeping the things you learned and liked as a child and simply adding onto them as we grow older interesting. When we read as a child, we often have a book series or a few that really stick out with us as we grow older. The characters, the morals, and the ideals grow up with us and can affect how we see and react to the world, whether we realize it or not. Instead of completely discarding them, allowing the new things we learn and read to be added to our older experience can enrich our lives even greater and allow us to be more well-rounded in life.

I would like to explore more of what Lewis talks about in regards to what is good children’s literature and how it can affect us as adults, and how we should add onto the things we experienced as a child rather than throw them away. Society still pushes that we be “sensible” and “serious” adults—perhaps this stigma against “childishness” is more harmful to society than we think it is.

(1). Lewis, C.S. Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories. Ed. Walter Hooper. New York: Harvest Book, Harcourt, Inc. 1994.