Word of the Day: Colleague

Paul Schleifer

A colleague is “’an associate in office, employment, or labor,’ 1530s, from Middle French collègue (16c.), from Latin collega ‘partner in office,’ from assimilated form of com ‘with, together’ (see com-) + leg-, stem of legare ‘send as a deputy, send with a commission,’ from PIE root *leg- (1) ‘to collect, gather.’ So, ‘one sent or chosen to work with another,’ or ‘one chosen at the same time as another,’” according to www.etymonline.com.

Interestingly, English college comes also from com- and *leg-, but the Latin word that leads to college is actually the plural of the word that leads to colleague.

You might wonder what it means to be an “assimilated form.” Assimilation is a process by which a sound becomes more like a nearby sound. The two sounds can be in the same word or in different words. The most frequent kind of assimilation within a word is called anticipatory assimilation, when a sound earlier in the word changes to be more like a sound that comes later in the word. So in colleague, the m in the prefix com– becomes l, like the l which follows it. You can probably see that colleague is much easier to say than comleague, just as college is easier to say than comlege.

Today is the birthday of Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, back in 1811 in Göttingen, Westphalia (in the northwestern part of modern-day Germany). At the University of Göttingen, he studied mineralogy, mathematics, and chemistry, earning his Ph.D. in 1831 (yes, count the years). He toured Europe for a couple of years after completing his degree, and then he took a position as lecturer at Göttingen.

Following Göttingen, he taught at the Polytechnic School of Kassel, the University of Marburg, the University of Heidelberg, and the University of Breslau. Among his accomplishments is “the use of iron oxide hydrate as a precipitating agent is still today the most effective antidote against arsenic poisoning. This interdisciplinary research was carried on and published in conjunction with the physician Arnold Adolph Berthold” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bunsen). He also “created the Bunsen cell battery, using a carbon electrode instead of the expensive platinum electrode used in William Robert Grove’s electrochemical cell.”

In 1852, when he moved to Heidelberg, he began an association with a British chemist named Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe. They worked together for 7 years on “the photochemical formation of hydrogen chloride (HCl) from hydrogen and chlorine. From this work, the reciprocity law of Bunsen and Roscoe originated.” Then he began to work with Gustav Kirchhoff on “emission spectra of heated elements, a research area called spectrum analysis. For this work, Bunsen and his laboratory assistant, Peter Desaga, had perfected a special gas burner by 1855, which was influenced by earlier models. The newer design of Bunsen and Desaga, which provided a very hot and clean flame, is now called simply the ‘Bunsen burner,’ a common laboratory equipment” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bunsen). Then, “in the summer of 1859, Kirchhoff suggested to Bunsen that he should try to form prismatic spectra of these colors. By October of that year the two scientists had invented an appropriate instrument, a prototype spectroscope. Using it, they were able to identify the characteristic spectra of sodium, lithium, and potassium. After numerous laborious purifications, Bunsen proved that highly pure samples gave unique spectra. In the course of this work, Bunsen detected previously unknown new blue spectral emission lines in samples of mineral water from Dürkheim. He guessed that these lines indicated the existence of an undiscovered chemical element. After careful distillation of forty tons of this water, in the spring of 1860 he was able to isolate 17 grams of a new element. He named the element ‘caesium’, after the Latin word for deep blue. The following year he discovered rubidium, by a similar process.” For this work, Bunsen and Kirchhoff were the first recipients of the Davy Medal, which is awarded by the Royal Society of London for outstanding work in chemistry.

Bunsen is famous today for the Bunsen burner, which we all had to use in our high school chemistry classes. But some of his other accomplishments are really more significant in the history of science. But perhaps what is most important is that most of what he accomplished in his career was while he was working with an important colleague.

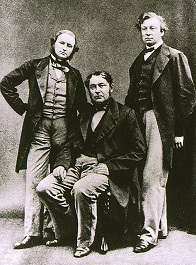

The image is a picture of Gustav Kirchhoff (left), Robert Bunsen (center), and Henry Enfield Roscoe (right) (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kirchhoff_Bunsen_Roscoe.jpg). The source is Roscoe, Henry Enfield, The Life & Experiences of Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe (London and New York: Macmillan, 1906), between pages 72 and 73, and the photograph was taken in 1862.