Stomaching the Truth of Humanity in Shakespeare’s Othello

Jahanna Bolding

It’s a fact: humans are drawn to drama. And no, I don’t mean the kind of pointless school drama that centers on antagonizing prattle, but rather drama in art. So, why do we enjoy drama? Sure, some drama is triumphant and glorious, but some drama is just plain painful. What’s the point?

Though this question does not have one comprehensive answer, I will submit that one of the most valuable aspects of drama in art is its ability to exaggerate (and therefore magnify) specific aspects of human nature that would otherwise be hidden from our eyes.

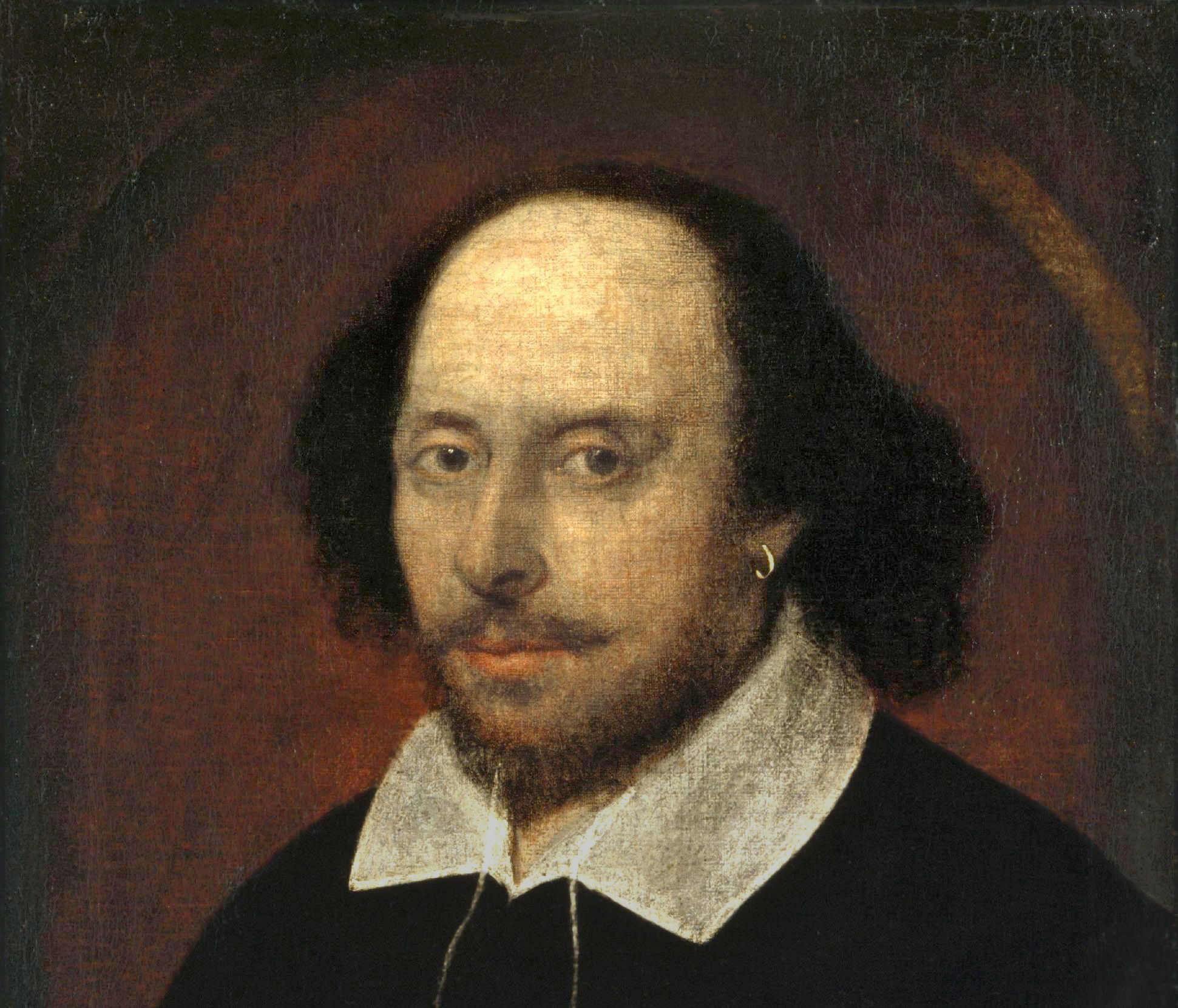

While reading C. S. Lewis’s autobiographical account of his conversion, Surprised by Joy, I found that he mentions that his father Albert Lewis, a passionate rhetorician with a love for poetry, quite enjoyed reading Shakespeare’s Othello. After investigating Othello for myself, it is totally unsurprising that Lewis Sr. enjoyed the twists and turns of such an intensely dramatic tragedy. So, in contemplating artful drama under the idea that certain aspects of human nature will be revealed through analysis, what does Othello disclose to us about the human condition? Among other things, Othello reveals a dark, depraved side of human nature in its discussion of jealousy, greed, hatred, and deception.

First, Othello speaks at length about the subject of human jealousy and insecurity. There are many questions raised about Othello’s jealousy – mainly, where did it come from? What provoked such an intense envy? In the beginning of the play, Othello seems to be exactly what everyone else believes him to be: an honorable and patient war hero who loves his wife tenderly. However, as soon as Iago begins to plant the doubt of Desdemona’s fidelity, Othello’s Jekyll seems to immediately give way to his Hyde. Othello’s sudden, all-consuming jealous rage blind him to truth and grace, and eventually leads to both Othello and Desdemona’s undoing. The argument that Othello’s jealousy was nonexistent before Desdemona’s suggested affair seems improbable when considering the rapidity to which he descends into this all-consuming rage. It seems more likely that this jealousy of Othello’s was already there, but merely subdued for a time. Othello basically had everything that he wanted: fame, glory, honor, and a beautiful wife. Why would Othello need to be jealous? However, when Othello’s stability is threatened, the jealousy and rage that had probably been held at bay for years came rushing to the surface. Othello struggles with deep insecurities related to his age and race, and he allows these doubts to completely saturate his mind in jealousy instead of sober-mindedly and patiently seeking the truth of the situation. Are we not the same, allowing our wild insecurities and the sins of our hearts to overpower our reason and ability to extend grace? Of course we are. That’s why Othello’s character leaves readers so uncomfortable – because his depravity is so like our own.

Next, Othello touches on aspects of human greed. Whether this greed manifests itself in the form of lust for the body, for power, or for status, many of the characters in this play are plagued by an insatiable greed. For example, Othello has an unquenchable greed for what he deems to be revenge. He obsessively longs for bloody justice for the crimes done against him by Cassio and Desdemona, and he will go to any lengths to execute it. Roderigo also shows evidence of greed in his lusting after Desdemona, even though she is happily married. Though Roderigo shows signs of repentance for this by the end, his greed helps jumpstart Iago’s whole malicious plot, and it is quite noteworthy. Speaking of Iago, his greed is perhaps the most interesting of all. What exactly is he greedy for? Is it power? Psychological dominance? The sheer thrill of literally destroying people’s lives? There is much ambiguity in Iago’s character, which is why he is such a terrifying villain for this particular tale. Whatever his specific vice is, Iago is not satisfied, even in the end after multiple deaths occur as a result of his wily schemes. Are we not also like this – desperate beyond belief to find satisfaction in the fulfillment of something, when all our hearts really long for is the fullness of Christ?

Along with jealousy and greed, Shakespeare also hits on the subject of human hatred. Othello hates so bitterly what he once seemed to cherish so dearly. How did this happen? How could jealousy turn his heart cold as stone in mere moments? As a result of the fall, humans are more prone to hatred than we are to love. Our hearts are dark, cold, and unpredictable, only warmed by the light of Christ and the work of the Spirit. In this play, the barren wasteland that is the human heart pre-regeneration is a breeding ground for hatred. Othello hates Cassio and Desdemona, Roderigo hates Cassio, Emilia hates Iago, and Iago seems to hate everyone. The only character who seems to love honestly, fully, and graciously is Desdemona, but she is slaughtered as a result of this vile hatred.

Overall, one of the biggest questions that the play poses for readers is why does Iago do what he does? Why all of the deception, defiance, and destruction? Iago gives petty reasons for his crimes, sure, but nothing that he defends seems to merit the destruction that ensues. His tendency towards deception in all things is unsettling to say the absolute least. In reality, how much could have been solved in this play by just a few characters sitting down for a moment and having an honest conversation instead of everyone only listening to Iago’s honey-dipped lies? That is what makes this play so heart wrenching: all of this pain could have been avoided if the deception wasn’t so deep.

Iago’s character holds great amounts of ambiguity and complexity, and this analysis is not an attempt to offer a simplistic or generalized reason behind his actions. This is not a cop-out or an attempt to moralize a complex story. However, in accordance with the rest of the play, the state of Iago’s heart, as a fallen human, cannot be ignored. Jeremiah writes in Jeremiah 17:9 that “the human heart is deceitful above all things and desperately sick; who can understand it?” This is reality. Iago’s heart is dark, and his motives are not fully understandable because evil makes very little logical sense.

Flannery O’Connor wrote, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it emotionally.” Grappling with the deep, dark depths of the human heart is difficult and painful, but depravity is true nonetheless. But, what do we do with this truth about the natural state of humanity? Shrink in fear of our own hearts?

Absolutely not. We can, as regenerated Christians, use the dramatic magnification in “Othello” to encourage us to approach the throne of grace with humility in recognition of our own tendency to wander. In addition to that, we can use Othello for introspective purposes. Who do you relate with in this tale? What can you learn about your own specific tendencies, and how can you use this information, through the lens of the gospel, to grow in grace?

It is not, in the end, surprising to me that Lewis Sr. enjoyed reading Othello. He was a passionate man with a large personality, and it makes sense to me that he was drawn to such a dramatic play. Honestly, I wish I could hear him speak of why he loved Othello so much—was it because of the intense drama, the rich characters, or the hard truths? Anyway, regardless of what drew him to Othello in the first place, one thing is certain: he had good taste.