Word of the Day: Gainsay

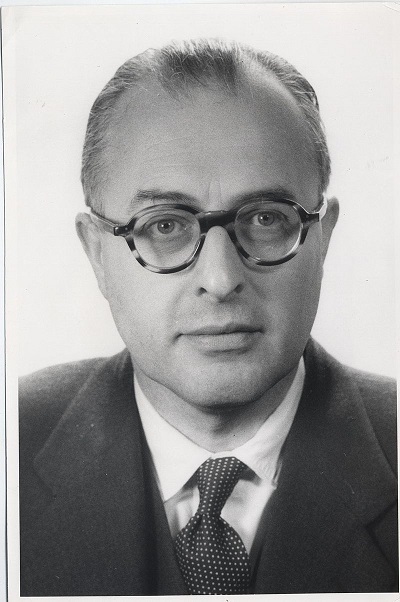

Paul Schleifer

If you were to ask my wife, she might tell you that gainsay is an apt word for me to write about because it means “1. to deny, dispute, or contradict. 2. to speak or act against; oppose” (www.dictionary.com). She seems to think that I contradict everything she says, though in truth I only oppose her when she is wrong (which is never, right?). According to www.etymonline.com, it appears in Middle English, “c. 1300, literally ‘say against,’ from gain- (Old English gegn- ‘against;’ see again) + say (v.). In Middle English it translates Latin contradicere. ‘Solitary survival of a once common prefix’ (Weekley, Ernest, An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, John Murray, 1921; reprint 1967, Dover Publications). It also figured in such now-obsolete compounds as gain-taking ‘taking back again,’ gainclap ‘a counterstroke,’ gainbuy ‘redeem,’ Gaincoming ‘Second Advent,’ and gainstand ‘to oppose.’”

If you look up any of these other words with the prefix gain-, you won’t find them.

On this date in 1952, a paper was at the US Electronic Components Symposium by a British electronics engineer. At the end of the paper was this quote: “With the advent of the transistor and the work on semi-conductors generally, it now seems possible to envisage electronic equipment in a solid block with no connecting wires. The block may consist of layers of insulating, conducting, rectifying and amplifying materials, the electronic functions being connected directly by cutting out areas of the various layers” (see Wikipedia).

The author of the paper later said, “It seemed so logical to me; we had been working on smaller and smaller components, improving reliability as well as size reduction. I thought the only way we could ever attain our aim was in the form of a solid block. You then do away with all your contact problems, and you have a small circuit with high reliability. And that is why I went on with it. I shook the industry to the bone. I was trying to make them realise how important its invention would be for the future of microelectronics and the national economy.”

What the engineer was describing was the integrated circuit, or microchip. If you think about it, much of what constitutes life in the 21st century is based upon this seemingly simple invention. I would not go so far as to say that the microchip is the most important invention of the 20th century, but I think it would have to be in the top 10 at least.

The author of the paper, and the inventor of the first prototype of the microchip, graduated from the relatively undistinguished Manchester College of Technology. His first job was with a company that employed technicians to examine valves that were returned as faulty, and part of that job was to look for evidence of rough handling so that the company would not have to provide free replacement parts. He eventually worked on radar for the Brits during WWII, work for which he was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

What’s interesting is that a man from a relatively lower-class background, who began his career in a fairly undistinguished fashion, eventually became known as the Prophet of the Integrated Circuit. We think of genius as something that manifests itself early in a person’s life and career, but in this case the genius didn’t show up until middle age.

What’s even more surprising, perhaps, is the name of this British engineer: Geoffrey Dummer. And you cannot gainsay it.

The image is a scanned photograph of Geoffrey Dummer in the 1950s, provided through WikiMedia.