Word of the Day: Egress

Paul Schleifer

The noun egress means three different but similar things: “the act of going out,” “the place where one goes out,” or “the right to go out.” There is also a verb egress, which means “to go out”; in speech you can tell the difference between the noun and the verb by the location of the stress, the first syllable in the noun and the second syllable in the verb.

According to www.etymonline.com, egress entered the language around 1530 from Latin egressus, meaning “a going out,” “noun use of past participle of egredi ‘go out,’ from ex ‘out’ (see ex-) + -gredi, combining form of gradi ‘step, go’ (from PIE root *ghredh-‘to walk, go’).” Etymonline suggests that egress is “Perhaps” a back formation from egression, which first appeared in English in the 1420s.

The functional shift that occurs with egress, from its use as a noun to its use as a verb, comes early on (to my surprise—I see functional shift as an annoying habit of moderns). The first recorded use of egress as a verb is 1578, less than 50 years after it first appeared.

On this date in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the Selective Service Act of 1917. According to a wiki on Wikipedia, “Owing to very slow enlistment following the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on April 6, the Selective Service Act of 1917 (40 Stat. 76) was passed by the 65th United States Congress” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_Service_System#1917_to_1920). It’s interesting that this “slow enlistment” was determined after just a month of being at war. And the slowness may have indicated that the American people were not all that interested in fighting a war in Europe that was between European powers over European issues.

The draft age prescribed by this act was 21 to 30, and that 30 was later raised to 45 in August of 1918, even though it was clear by then that the Allies were going to win; the end of the war three months later. Furthermore, the act stayed in effect until 1920.

One might think that such a draft would violate the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which clearly states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The Wikipedia article says that the Supreme Court allowed selective service under the terms of the Butler v Perry decision of 1916, so I took a look at that decision, and it is pretty wild. In its Acts of 1913, the State of Florida provides a way of maintaining roads: “Every able-bodied male person over the age of twenty-one years, and under the age of forty-five years, residing in said county for thirty days or more continuously … shall be subject, liable and required to work on the roads and bridges of the several counties for six days of not less than ten hours each in each year when summoned so to do, as herein provided; that such persons so subject to road duty may perform such services by an able- bodied substitute over the age of eighteen years, or in lieu thereof may pay to the road overseer on or before the day he is called upon to render such service the sum of $3.” That’s right. All able-bodied men were required to give 60 hours of free labor to the State of Florida to work on the roads. And the Supreme Court upheld this law. Can you imagine the State of South Carolina passing such a law today? How quickly would the Supreme Court strike down such a law.

And yet, the Selective Service Act was somehow passed by the Congress in order to provide bodies for our leaders to send across the ocean to fight a war that had nothing to do with our national security. At least today’s military adventurism employs an all-volunteer army, though there are occasionally voices that want to reinstitute the draft.

Although the draft was allowed to end in 1920, it was reinstituted in 1940 by FDR even though the US was not attacked until late in 1941. After WWII, it was kept in place until 1947, and then brought back again in 1948. The draft remained in place, though the details of the draft law changed, until it was canceled by executive order of Gerald Ford in 1975. The country’s weariness following the long war in Vietnam and the protests against it had a lot to do with that cancelation. But in 1980, a year before leaving office, Jimmy Carter instituted a system of draft registration, whereby young men (not women, though) must register with the selective service bureaucracy even though none of those young men have yet to be drafted. Carter supposedly made this executive decision, which he could do because the Selective Service Act of 1948 has been amended but never ended, because the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979.

Draft registration still exists. In 2016, nearly 100 years after military conscription was first introduced by Wilson, a bill was introduced in Congress to end the draft completely, but it has not been enacted. That’s kind of too bad. Perhaps an end to the draft completely will provide a means of egress to the Great American World Policeman.

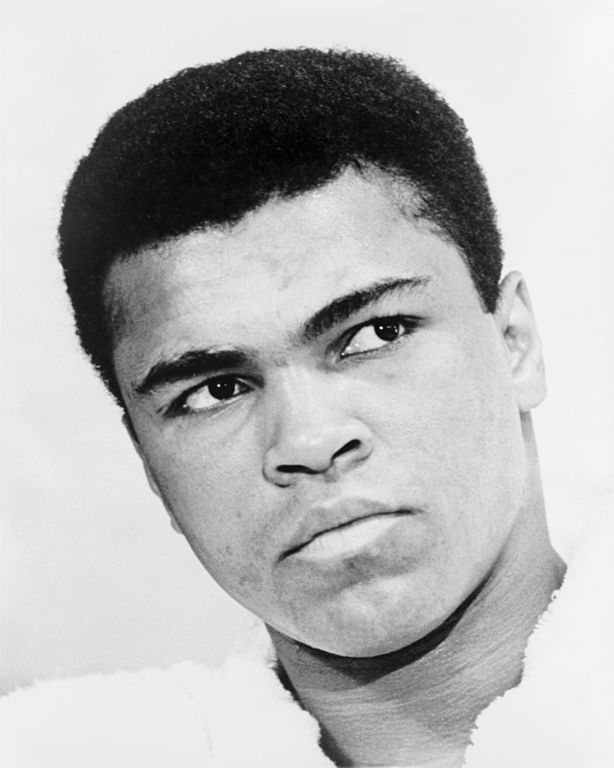

The photo of Muhammad Ali was taken by Ira Rosenberg in 1967 and can be found at the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3c15435. Ali was deprived of his world boxing championship in 1966 because of his refusal to be drafted by the U.S. military. He was convicted of draft evasion, but his conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1971. Nevertheless, he sacrificed four years of what is still the most successful boxing career in the history of the sport.