Word of the Day: Recidivate

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of www.wordthink.com, is recidivate, a verb meaning “To return to a previous pattern of behavior. Relapse: go back to bad or criminal behavior,” according to the website. According to www.dictionary.com, it means “to engage in recidivism; relapse.” Etymonline says, “’fall back; relapse,’ 1520s, from Medieval Latin recidivatus, past participle of recidivare ‘to relapse’ (see recidivist).”

If you go to recidivist on www.etymonline.com, you find a much more thorough, though different, etymology: “’relapsed criminal,’ 1863, from French récidiviste, from récidiver ‘to fall back, relapse,’ from Medieval Latin recidivare ‘to relapse into sin,’ from Latin recidivus ‘falling back,’ from recidere ‘fall back,’ from re- ‘back, again’ (see re-) + combining form of cadere ‘to fall’ (from PIE root *kad- ‘to fall’). Recidivation in the spiritual sense is attested from early 15c., was very common 17c.” Looking at recidivism gives you this: “’habit of relapsing’ (into crime), 1882, from recidivist + -ism, modeled on French récidivisme, from récidiver.” So even though the version of the word that we are likely most familiar with, recidivism, is the most recent version.

According to OnThisDay.com, on this date in 1931, baseball’s National League adopted a less lively baseball for the upcoming 1931 season. You might wonder why. So here’s some background. In the earliest days of baseball, balls were not uniform. Some people say that the pitchers made their own baseballs, which were much softer and actually varied in size. When baseball finally got itself organized, the leagues accepted a proposed uniform ball created by a pitcher whose last name was Spalding (sound familiar?). That ball was the standard through the 1910 season, a time in baseball known as the dead-ball era.

Why the dead-ball era? In the last season of the dead-ball era, the leader in batting average was Nap Lajoie, of the Cleveland Naps (they changed the name to Cleveland Indians after Nap Lajoie left after the 1914 season), who batted .383. Lajoie had 227 hits, 165 of which were singles and 51 of which were doubles. Not bad. Sherry Magee, of the Philadelphia Phillies, led baseball with 110 runs scored to go with his 123 RBI, which also led baseball. Again, not bad, especially when you remember that they played only 154 games instead of the 162 games that the leagues play now. The home run leaders for 1910 were Jake Stahl of the Boston Red Sox, Frank Schulte of the Chicago Cubs, and Fred Beck of the Boston Doves (National League); each had 10. 10! Ten home runs led both leagues.

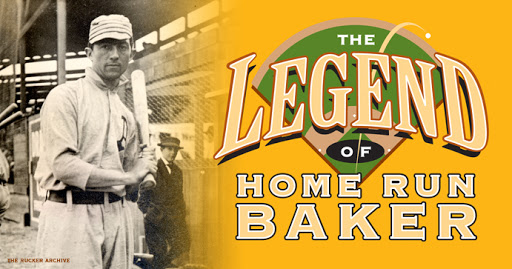

Then the National League changed the center of the ball from rubber to cork, and the numbers picked up. 1911: Frank Schulte led the NL with 21 homers; 1913-15: Gabby Cravath of the Phillies led the NL with 19, 19, and 24; after a lull in the numbers, George Kelly of the NY Giants led the league with 21 in 1921; in 1922, Rogers Hornsby of the Cardinals led the league with 42; then Cy Williams in 1923 led the league with 41. By contrast, the Philadelphia Athletics’ Frank Baker led the AL four consecutive years in the 1910s, led the Athletics to 3 World Series wins and then helped the Yankees get to the World Series in 1921 and 1922, and in 14 years hit a total of 96 home runs, and Frank Baker’s nickname was “Home Run Baker,” and he’s considered the first home-run king of the modern era.

Then in the 1920s, both leagues adopted a livelier ball, sometimes called the Rabbit Ball. Its livelier properties may have come from the use of Australian wool on the inside, or it may have come from a slight increase in the size of the ball, or from flatter seams (the latter two would have made it harder for pitchers to control the ball); changes to rules about the infamous spit ball may have helped the hitters. But in the 1920s, the nature of baseball in both leagues changed.

In 1930, Bill Terry of the New York Giants batted .401, with 254 hits. Hack Wilson of the Chicago Cubs led baseball with 56 home runs, followed by Babe Ruth with 49, Lou Gehrig with 41, and Chuck Klein of the Phillies with 40. To get to the “leader” with just 10 home runs, you have to go past the 41 players above Ethan Allen and the 7 others who hit only 10 that year.

In 1930, the Philadelphia Phillies had a team batting average of .315 (.324 if you leave out the pitchers); the Phillies were third in the 8-team NL with 126 home runs; they led the league in hits, and they were fourth in runs scored; they apparently didn’t have a lot of speed because they were last in triples and stolen bases. But with all that offense, they lost 102 games!

That’s when the pitchers rebelled, and baseball had to dampen down the baseball. The next year, 1931, Ruth and Gehrig were the only two players over 40 home runs, and only 27 hitters had more than 10. In 1934, the two leagues agreed upon regulating all baseballs and actually published the ingredients.

The next big change in the baseball came in 1943; as a result of the war, rubber was hard to come by, and the substitute that baseball hit upon was not the same. Nobody could hit. But that baseball lasted only one year because of the manufacture of synthetic rubber, and the numbers picked up again.

But the quest to find just the right formula of offense versus pitching continued even after the ball was standardized. By the late 1960s, the pitchers were dominating once again. In 1968, Bob Gibson led baseball with a 1.12 earned run average—an absolutely ridiculous number. Seven pitchers had an ERA under 2. Carl Yastrzemski of the Red Sox led both leagues with a .301 average (lower than the Phillies whole team in 1930). The White Sox had only one player with more than 10 home runs, and the fearsome Yankees hit .214. So what did baseball do? It lowered the pitcher’s mound to reduce the advantage that pitchers had by throwing downhill; the mound, which had been 15 inches above the rest of the playing field was lowered to 10 inches. And the change worked, though the offense did not improve as much as it did in the steroid era, from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. In 1997, 13 different players hit more than 40 home runs.

The numbers have diminished since the early 2000s, with the advent of testing for performance enhancing drugs (PEDs). But if they diminish too much, be sure that baseball will find a new way to adjust. Sports people love to recidivate.

The photo is of Frank “Home Run” Baker, who led the Philadelphia Athletics to the 1911 World Series title (http://www.thisgreatgame.com/1911-baseball-history.html).