Word of the Day: Infinitesimal

Infinitesimal: Word of the Day

Today’s word of the day, thanks to www.wordgenius.com, is infinitesimal, an adjective meaning “1. extremely small” or “2. too small to be measured.” According to www.etymonline.com, the adjective entered the language in the “1710 (1650s as a noun), ‘infinitely small, less than any assignable quantity,’ from Modern Latin infinitesimus, from Latin infinitus ‘infinite’ (see infinite) + ordinal word-forming element -esimus, as in centesimus ‘hundredth.’” The word is, of course, derived from the adjective infinite, which entered English much earlier, in the “late 14c., ‘eternal, limitless,’ also ‘extremely great in number,’ from Old French infinit ‘endless, boundless’ and directly from Latin infinitus ‘unbounded, unlimited, countless, numberless,’ from in- ‘not, opposite of’ (see in- (1)) + finitus ‘defining, definite,’ from finis ‘end.’” In other words, something that is infinitesimal is so small that it is small without limit, without end.

According to scholars at the University of Paris, it was on this date in 1345 that “what they call ‘a triple conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter and Mars in the 40th degree of Aquarius, occurring on the 20th of March 1345.’″ The result of that triple conundrum? The creation of what became known as the Black Plague.

Pretty much everybody has heard of the Black Plague, or the Bubonic Plague. But in case you haven’t, the Bubonic Plague struck Europe in the middle of the 14th century, and it re-appeared frequently in the centuries that followed. It came from Asia, and it landed in Europe in 1347 when a dozen ships docked at the port of Messina, Sicily, in Italy. When the ships docked, the people who came to meet them were greeted with a true horror: most of the sailors were dead, and those who weren’t were very sick and covered with boils, called buboes (hence Bubonic Plague), swellings of lymph nodes that were extremely painful.

The Sicilian authorities were quick to force the ships back out to sea, but it was too late.

According to www.history.com, “The Black Death was terrifyingly, indiscriminately contagious: “the mere touching of the clothes,” wrote [the poet Giovanni] Boccaccio, “appeared to itself to communicate the malady to the toucher.” The disease was also terrifyingly efficient. People who were perfectly healthy when they went to bed at night could be dead by morning.”

There are various estimates for how many died from the plague. The traditional estimate is 1/3 of the European population, but some recent histories place the figure at 50 to 60%. The population in Europe prior to the Black Plague was something over 70 million, so somewhere between 20 and 35 million people died from it. It was a terrible and terrifying time for the people of Europe. And that does not include people from Asia, from the Middle East to the Far East; adding those victims, the estimates range from 70 to 200 million people.

So, what exactly is it that released this horrible plague upon the world. It was the “Yersinia pestis (formerly Pasteurella pestis),” a coccobacillus bacterium, with no spores.” It “can infect humans via the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis),” a flea which lives on rats until the rats die, at which point it seeks another host. “It causes the disease plague, which takes three main forms: pneumonic, septicemic, and bubonic” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yersinia_pestis), and it is the last that killed millions in the 14th century.

If it was this bacterium which killed all those people, why did the scholars at the University of Paris claim that it was a conjunction of the planets in the “age of Aquarius” that caused the Black Death to more than decimate Europe. They did so because they did not have the “germ theory of disease.” Although the germ theory was first proposed at the end of the first millennium CE, it was not accepted for well over eight centuries. It wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that scholars began accept this theory en masse. And it was only with the acceptance of the germ theory that doctors began to realize the source of the plague.

We seem to be experiencing a similar plague with the spread of the coronavirus, or COVID-19, though it is neither as contagious nor as deadly as the plague was. And while the plague was caused by a bacterium, COVID-19 is caused by a virus. The bacterium was passed to people through a flea, but the virus can be passed directly from human to human, though the Chinese government denied that truth for quite some time.

But the bacterium and the virus have, at least, a couple of things in common. One, they are deadly to humans. And two, they are infinitesimal, at least to the naked eye.

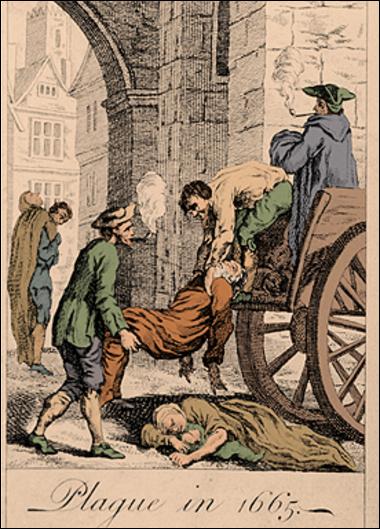

The drawing is of the great plague of London in 1665—yes, the plague reappeared in Europe over and over again until its true cause was discovered.