Word of the Day: Hapless

Today’s Word of the Day, courtesy of WordSmith.org, is hapless, an adjective meaning “unfortunate,” according to Anu Garg at A.Word.a.Day. He says that the etymology is “from Old Norse happ (good luck) + less, from Old English laes (without). Earliest documented use: 1400.” According to www.dictionary.com, the word is not recorded until about 1560, and the dictionary site adds “unlucky” and “luckless” as synonyms.

From www.etymonline.com, we learn that hap, a noun, enters the language “c. 1200, ‘chance, a person’s luck, fortune, fate;’ also ‘unforeseen occurrence,’ from Old Norse happ ‘chance, good luck,’ from Proto-Germanic *hap- (source of Old English gehæp ‘convenient, fit’), from PIE *kob- ‘to suit, fit, succeed’ (source also of Sanskrit kob ‘good omen; congratulations, good wishes,’ Old Irish cob ‘victory,’ Norwegian heppa ‘lucky, favorable, propitious,’ Old Church Slavonic kobu ‘fate, foreboding, omen). Meaning ‘good fortune’ in English is from early 13c. Old Norse seems to have had the word only in positive senses.” There is verb hap, “’to come to pass, be the case,’ c. 1300.” And, of course, there are a number of English words derived from hap: happy, hapless, mishap, haphazard, mayhap, and others.

On this date in 1789, Fletcher Christian led a group of mutineers who took over the HMS Bounty, deposing the ship’s captain, Lieutenant William Bligh.

The Bounty, a British naval vessel on a trip to Tahiti to gather breadfruit, with the intent of taking it to the West Indies, where, it was thought, it would be a nutritious food for the slaves, had sailed from England in 1787 and arrived in Tahiti in late October of 1788. It had traveled over 50,000 kilometers. It stayed in Tahiti for five months, during which time the crew gradually brought samples of the breadfruit on board. But during that time, most of the crew took shore leave and developed various relationships with the islanders, particularly with the women.

After 5 months of this, Bligh and the Bounty were ready to begin the long voyage to the West Indies. But many of the men were not so inclined. Nevertheless, they boarded the ship and set sail.

Accounts of the journey indicate that Bligh was a bit tough to deal with, making unreasonable demands, especially on the young Master’s Mate Fletcher Christian. At one stop for provisions, Bligh sent a shore party onto a relatively hostile island with Christian in command, allowing them to take muskets, but instructing them to leave their muskets in the boat. Attacked by islanders, Christian and his men were unable to complete the mission fully, and Bligh accused Christian of being cowardly. On another occasion, Bligh accused Christian of having stolen coconuts from the lieutenant’s cabin.

As Christian became depressed and morose, several other officers approached him and told him that if he were to lead a mutiny against Bligh, they would have his back. Finally, on the morning of April 28, Christian had had enough. He gathered some of his supporters, took over the storage unit containing the weapons, went to Bligh’s cabin, and dragged him up on deck. At that point, he found out that about half the crew were loyalists to Bligh.

The mutineers took the captain and most of the loyalists and put them onto an open boat. Then they turned the ship around and sailed back to Tahiti. The mutineers eventually split up, and Christian, along with the last small group of men and a number of male and female Tahitians, sailed to Pitcairn’s Island, which had been discovered once before but had been improperly positioned by cartographers. There, the group established a community which eventually thrived, though Christian was killed before he had a chance to see it.

Bligh and his men sailed some 6,500 kilometers and found shelter. Bligh worked his way back to England, where initially he was celebrated as a hero, since news of the mutiny had already reached England. But eventually, as the story came out from a variety of sources, including some of the mutineers who were eventually captured and returned to England for court martialing, Bligh’s reputation was damaged and many in the public became supporters of Fletcher Christian’s side.

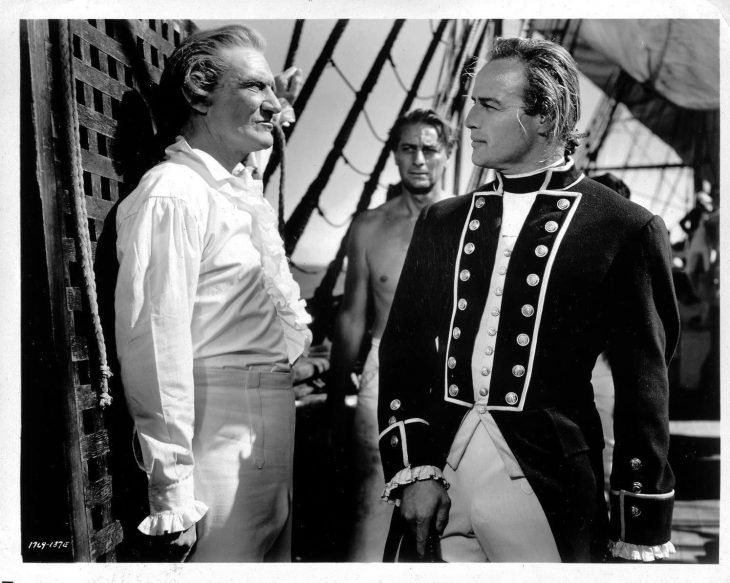

There have been a number of accounts of the mutiny on the Bounty, some factual and some fictional. An early silent film, made in Australia, was lost. Another film was shot in the 1930s in Australia. But an American film, also shot in the 30s, became a classic, with Charles Laughton as Captain Bligh and Clark Gable as Fletcher Christian. The movie was based upon the novel of the same name by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall—they actually did a trilogy, starting with Mutiny on the Bounty, then Men against the Sea, and Pitcairn’s Island. Another film based on the novel came out in 1962, with Trevor Howard as Bligh and Marlon Brando as Christian.

I remember that I read the trilogy when I was in Junior High School, and I saw the 1962 version of the film, probably on television. It was good, though I think I confuse it in my mind with The Caine Mutiny, starring Humphrey Bogart as Captain Queeg and Van Johnson as Lt. Steve Maryk, along with Fred McMurray, Josè Ferrer, E. G. Marshall, Lee Marvin, and Claude Akins, among others. Of course, in both cases, the majority of the characters were pretty much hapless.

Today’s photo is of Howard and Brando in the 1962 production of Mutiny on the Bounty.