Word of the Day: Incredulous

Today’s Word of the Day, courtesy of www.wordthink.com’s word of the day, is incredulous. Believe it or not, the adjective does not mean the same thing as incredible, which means “hard to believe.” Incredulous refers not to events or things but to people, and it means “disinclined or indisposed to believe; skeptical,” or “indicating or showing unbelief.”

According to www.etymonline.com, the word entered the English language in the “1570s, from Latin incredulus ‘unbelieving, incredulous,’ from in- ‘not’ (see in- (1)) + credulus (see credulous).” Of course, that leads us to the etymology of credulous: “’disposed to believe, uncritical with regard to beliefs,’ 1570s, from Latin credulus ‘that easily believes, trustful,’ from credere ‘to believe’ (see credo).” And that takes us to credo: “early 13c., ‘the Creed in the Church service,’ from Latin credo ‘I believe,’ the first word of the Apostles’ and Nicene creeds, first person singular present indicative of credere ‘to believe,’ from PIE compound *kerd-dhe- ‘to believe,’ literally ‘to put one’s heart’ (source also of Old Irish cretim, Irish creidim, Welsh credu ‘I believe,’ Sanskrit śrad-dhā- ‘faith, confidence, devotion’), from PIE root *kerd- ‘heart.’ The nativized form is creed. General sense of ‘formula or statement of belief’ is from 1580s.”

On this date 105 years ago the Lusitania was sunk by a German U-Boat off the coast of Ireland. It is an even that we learned about in school, many years ago, as the reason the USA entered World War I, but that was, of course, not true. The sinking of the Lusitania happened in 1915, and the USA did not enter the war in Europe until 1917. The real inciting event that led to a declaration of war by the Congress was the Zimmerman Telegram, in which the German government offered to help Mexico win back some of the territories lost in earlier wars between the USA and Mexico.

But even that wasn’t really the reason, in my humble opinion. The real reason was that American banks had made large loans to help the British and French in their fight against the Germans.

When the war started in 1914, Woodrow Wilson, the American president, quickly encouraged Americans to remain “neutral in thought as well as in deed.” Wilson allowed trade to continue between the USA and all the European countries. But the British established a blockade against the Germans, and while initially the blockade allowed for neutral countries to continue trading with the Axis powers, gradually it prevented more and more items from getting through. Britain’s intent was to starve the Germans and Austrians into surrendering. And it worked. By 1916, the Germans were having to deal with food riots.

The Germans initiated open warfare around the British Isles in 1914 using their Unterseeboots, or U-Boats. Wilhelm Bauer had invented the first U-boat in 1850, though it did sink. Still, the effort to perfect the submarine continued, and the Germans made it a powerful weapon in the first world war. The British, at the time, commanded the open seas. The Germans knew that the US was shipping weapons to the British in the holds of passenger liners, including the Lusitania. They also knew that the British had begun to arm merchant ships and passenger liners because the U-boats often surfaced before firing their torpedoes. So the U-boats began attacking without any warning, and on May 7, 1915, one sank the Lusitania, and over 1100 passengers died. Woodrow Wilson sent a letter to the Germans demanding that this kind of warfare be stopped, and the Germans agreed, even though it essentially left the seas in the hands of the British. Yet the Americans did not enter the war.

In 1916, Wilson’s campaign slogan was “He kept us out of war.” Americans, despite the Lusitania, remained neutral. But as the war dragged out, the financial situation of all the participants worsened. Had it continued, the British and French economies would have been damaged perhaps beyond repair, certainly beyond the point where they could have paid back the American banks which had lent them the money to fight the war. So on the slight provocation of the Zimmerman telegram, the USA finally sent troops to Europe to end what was, essentially, a war among cousins.

In other words, the loss of a thousand lives was not enough to force Woodrow Wilson’s hand, but the potential financial losses of the banks was. Perhaps you are incredulous. Perhaps you do not want to believe that the US government could be so mercenary. Perhaps you want to believe that it was the sinking of the Lusitania 105 years ago really was the reason for our entrance into WWI. But the actual timeline says different.

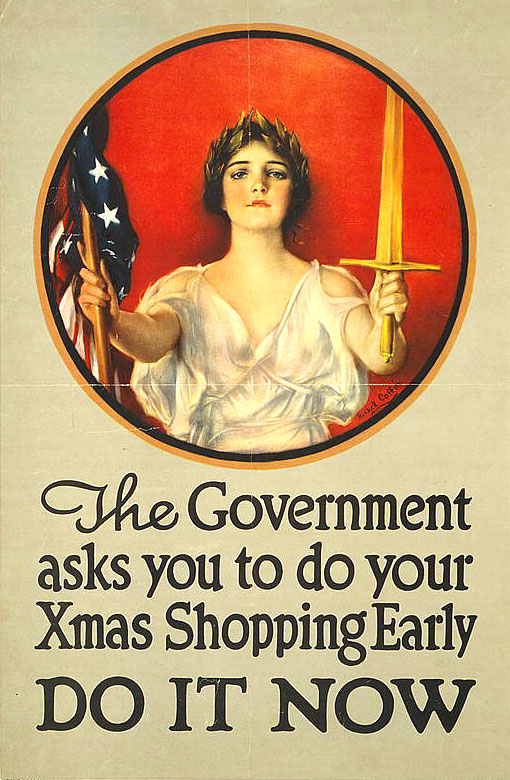

The photo for today is of a 1918 poster showing just how important the economy was to the government after the war had ended. The cynicism matches anything I can think of today. It came from https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/women-and-children-the-secret-weapons-of-world-war-i-propaganda-posters/.