Word of the Day: Noodge

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the Oxford English Dictionary, is noodge. If you look up the word on www.dictionary.com, you will learn that it is just a variant of nudge (a slight or gentle push or jog, especially with the elbow), but not according to the OED and some other sources. According to the OED, noodge comes from a Yiddish word which means “to pester, to nag.” YourDictionary.com takes it a little farther: “to annoy persistently,” “to annoy with persistent complaining, asking, urging, etc.” The OED says that the word comes from the “Yiddish nudyen to bore, pester,” which itself comes from the “Polish nudzić to bore, weary, make a nuisance of oneself or Russian nudit′ to wear out (with complaints, questions, etc.).” As a verb, noodge can be either transitive (takes a direct object) or intransitive, and it can also be a noun (“You’re such a noodge”).

On this date in 1861, an election was held in 50 counties in what at the time was western Virginia to determine the popular opinion regarding seceding from the state of Virginia. The vote was overwhelmingly in favor of secession, though the voter turnout was low.

First, some background. Despite a treaty with the Iroquois making what is today West Virginia their hunting ground, colonists from Virginia and Pennsylvania began moving into the area west of the Blue Ridge mountains around 1734. The land’s ownership was disputed until after the American Revolution, but eventually it was recognized all around that these counties were part of Virginia. But there were problems. The people of West Virginia comprised a minority of the state, and most of the power inhered in the plantation owners and shipping interests of the eastern part of the state. Many in the northwestern part of Virginia were anti-slavery, having come from states like Pennsylvania rather than from the tradition South.

The problems came to a head in 1861, when Virginia seceded from the United States of America. In April of that year, the convention in Richmond, Virginia, the state’s capital, voted on the question of secession. The vote was for secession, but the representatives from West Virginia voted 17 for and 30 against. On May 23, 1861, a referendum was held throughout the state to ratify the Ordinance of Secession. A majority of the voting citizens of the state approved, but in West Virginia, the vote was over 30,000 against secession and under 20,000 in favor. So Virginia, including those counties in what would soon become West Virginia, seceded from the Union.

Some of those who objected to secession met twice in Wheeling and declared the secession invalid and the government in Richmond void because they had rebelled against the USA. The Wheeling Convention created a Restored Government under the auspices of the federal government. The Restored Government even elected US Senators (this was back when US Senators were chosen by the state legislature rather than by a popular vote—a system we should return to) to go to Washington. So Virginia, for a time, had two governments, one under the auspices of the CSA, and the other under the USA.

And this was the time for the West Virginia secessionists to act. In the USA, a state cannot be derived out of a larger state without the permission of the larger state. This happened in 1819 when Massachusetts approved the District of Maine’s becoming a separate state, a choice approved by the voters of the District of Maine by a more than 2-1 margin. And the Restored Government of Virginia did indeed approve the counties that now comprise West Virginia.

So on October 24, 1861, the citizens of West Virginia voted 18,408 in favor of statehood and only 781 against statehood. Of course, a lot of people who thought the Restored Government was illegitimate chose not to participate in the vote, but that was their choice. So West Virginia became a state.

I think that one thing we can learn from the secession of West Virginia from the rest of the state is that smaller government units can actually be more representative of the people. The needs and interests of the people of the western counties were far different from those of the people who lived on the coast, and the fact that a majority of the people lived on the coast only made a tyranny of the majority more likely, not more palatable. We see a similar relationship in Oregon and Washington in our own century. The people who live in the eastern parts of those states have almost nothing but artificially drawn lines in common with the people who live on the west coast. The same is true in California.

But even more, the people who live in a majority of the states in the USA have little or nothing in common with the people who live on the two coasts, and yet the people on the two coasts have an enormous say over national policy, and yet their parochial interests work against the interests of people in other states. This is why the Constitution has the Electoral College and the two senators per state rule, to allow the smaller states to have some say in the national government. Otherwise, the smaller states would be completely controlled by the larger.

Personally, I think the USA is too large, with a central government that is too powerful and a people too diverse to ever have real unity. People often talk about how much more unity countries like Norway and Denmark have over issues like the social safety net, but those countries are much smaller and much more homogenous, at least in terms of interests.

But what would it take to create several smaller nations out of the current USA? I think it would take a lot of noodging by the people.

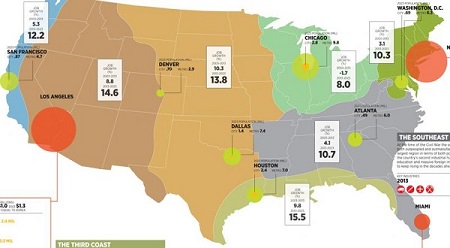

There are lots of variations on what a split-up USA might look like, from as few as two countries to as many as 33. Today’s image is one of those many suggestions from David Brown, writing on the KUT 90.5 FM website (https://www.kut.org/post/map-carves-us-seven-nations-and-splits-texas-three-ways).