Word of the Day: Reciprocal

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of WordThink, is reciprocal (http://www.wordthink.com/reciprocal/), an adjective meaning “Done or performed in return.” I should give the people at WordThink some props since I use their words occasionally. Here is how they describe their founding: “While there are many dictionary sites that provide a “Word of The Day” listing, they often include obscure words that would never be used in a typical conversation, email, or letter. When the “Word of The Day” from one of the leading dictionaries was eleemosynary (adj. relating to, or supported by charity) — we said ‘enough is enough’ and created WordThink.” Then again, I think there is room for both kinds of approaches to expanding and improving vocabulary.

According to www.etymonline.com, reciprocal means “’moving backward and forward, alternating; mutually exchanged or exchangeable; having an interchangeable character or relation, mutually equivalent and correspondent,’” and entered the language in the “1560s, with -al (1) + stem of Latin reciprocus ‘returning the same way, alternating,’ from pre-Latin *reco- proco-, from *recus (from re- ‘back;’ see re-, + -cus, adjective formation) + *procus (from pro- ‘forward,’ see pro-, + -cus).” So historically, it seems, the word has undergone the linguistic process called narrowing, where a word that once had a broader meaning now has a narrower meaning.

He was such a good friend of Huey P. Newton, the author of Revolutionary Suicide (1973) and co-founder of the Black Panther Party, that he joined the Black Panthers in 1979. Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychology professor and author of numerous books, including The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), said of him, “’one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought’” (https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/201601/trivers-pursuit). In the 1970s, he published five papers that were enormously influential, and then he stopped publishing for a long time. He was at Harvard University, but then he left in 1978 to teach at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He taught himself calculus when he was just 13 years old.

His name is Robert Trivers.

The second of the five papers Trivers published in the 1970s concerned the factor that drives sex differences across species. That factor is parental investment, according to Trivers (ibid). The idea is that males and females in animal species invest differing amounts of time in raising offspring, and the difference in the investment time determines sexual choices.

In another of the five papers, Trivers hypothesized that children are not just passive recipients of parental interest but are active players, thus creating the notion of parent-child conflict as well as sibling rivalries.

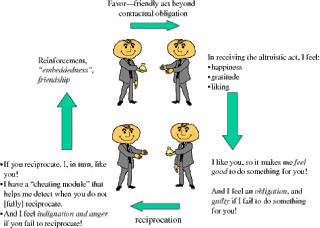

But the topic that interests me the most of all the five was the subject of the first of the five papers: “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism,” The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 46, No. 1 (March, 1971): pp. 35-57 (https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/Trivers-EvolutionReciprocalAltruism.pdf). Here is the abstract:

A model is presented to account for the natural selection of what is termed reciprocally altruistic behavior. The model shows how selection can operate -against the cheater (non-reciprocator) in the system. Three instances of altruistic behavior are discussed, the evolution of which the model can explain: (1) behavior involved in cleaning symbioses; (2) warning cries in birds: and (3) human reciprocal altruism.

Regarding human reciprocal altruism, it is shown that the details of the psychological system that regulates this altruism can be explained by the model. Specifically, friendship, dislike, moralistic aggression, gratitude, sympathy, trust, suspicion, trustworthiness, aspects of guilt, and some forms of dishonesty and hypocrisy can be explained as important adaptations to regulate the altruistic system. Each individual human is seen as possessing altruistic and cheating tendencies, the expression of which is sensitive to developmental variables that were selected to set the tendencies at a balance appropriate to the local social and ecological environment.

Here’s the idea: according to Darwin’s theory of evolution, certain traits in an individual of a species make its ability to survive better than members of the species that lack that trait (it can work the other way as well, making an individual less likely to survive), and thus that individual will be able to spread its genes to offspring at a greater rate, in part because it survives. One trait that is adaptable to many species is what Trivers calls reciprocal altruism. Altruism is an individual’s unselfish concern for the good of others. It manifests itself in all kinds of ways, depending upon the species.

Some people think that altruism, by itself, is genetic. But Trivers argues that it is reciprocal altruism: in other words, I’ll do something for your benefit now, but I expect that you’ll do something for me in the future. If you don’t do something for me when the occasion offers, I’ll remember that, and the next time you need for me to be altruistic, I probably won’t. In some animal communities, the member that does not reciprocate is likely to lose the trust, the altruism, of all the members of the species, losing the groups protection, and making that selfish individual less likely to survive.

Of course, what the Christian faith (and some other faiths) teach is true altruism. Jesus, for instance, does not expect us to do Him a favor in the future. Altruism is supposed to be a feature of the kind of love parents have for their children, but how often is it truly so? Even parents often look for some kind of reciprocation, and that’s okay. Reciprocal altruism is better than no altruism at all.

Today’s image comes from the Evolution of Human Behavior blog (http://evolutionofhumanbehavior.blogspot.com/2011/04/reciprocal-altruism.html).