Word of the Day: Arbitrate

Today’s word is arbitrate, courtesy of the NY Times, and it means “to settle a dispute between parties with the goal of reconciling differences.” According to etymonline.com, the word first appears in the 1580s and comes from the word arbiter, which means “’person who has power of judging absolutely according to his own pleasure in a dispute or issue,’ from Old French arbitre ‘arbiter, judge’ (13c.) and directly from Latin arbiter ‘one who goes somewhere (as witness or judge),’ in classical Latin used of spectators and eye-witnesses; specifically in law, ‘he who hears and decides a case, a judge, umpire, mediator;’ from ad ‘to’ (see ad-) + baetere ‘to come, go,’ a word of unknown etymology.” An arbitrator is the same as an arbiter except that the former word is used in legal situations.

On this date in 1798, Kentucky became the first state in our nation’s history to nullify an act of Congress when it passed a resolution declaring that the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were unconstitutional.

Some background: the first big political debate in this country occurred between the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party. The Federalists believe in more power to the federal government, and the Democratic-Republicans believed the states should have more power. In 1798, the Federalists were led by President John Adams, and the Republicans were led by Thomas Jefferson. It was the Federalists who managed to do away with the Articles of Confederation, which created the first central government, and managed to pass the US Constitution, creating our current government. The Republicans feared that the Constitution would give the federal government too much power.

In 1798, the country had a falling out with France, which was currently at war with England, over a treaty signed by Washington to bring the USA closer to England. Many feared that war with France was imminent. In June and July of that year, Congress passed a series of laws to give the federal government the power to expel foreigners from countries we were at war with or foreigners who seemed to oppose the government during peace time. It also passed a law giving the federal government the power to imprison people who criticized the president or the federal government in general.

The target of that last act was primarily editors of newspapers that supported the Democratic-Republicans. Between 1798 and 1801, the government prosecuted 26 people under the Sedition Act, all opponents of John Adams, and many newspaper editors (https://www.history.com/topics/early-us/alien-and-sedition-acts).

Many people were disgruntled by the Alien and Sedition Acts, and two states, Kentucky and Virginia, passed resolutions declaring the acts unconstitutional. The Kentucky act was written by Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia act by James Madison, though few people knew it at the time. After all, had Jefferson and Madison been found out, they might have gone to jail for sedition.

The result of the Alien and Sedition Acts was that, in 1800, Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams for the presidency, and most of the acts either expired or were repealed. The only one that is still on the books is the Alien Enemies Act, which gave the government the power to restrain, imprison, or remove male citizens of countries at war with the USA. This same act was the basis for putting Japanese and Japanese-Americans in concentration campus during World War II by another advocate of a powerful central government, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The argument against the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 was simple: the USA was founded on certain basic principles, principles enshrined in the Bill of Rights. We have the right to free expression and a free press, even if that expression offends the president or the people in power. The Sedition Act outlawed any “’false, scandalous and malicious writing’ against Congress or the president, and made it illegal to conspire ‘to oppose any measure or measures of the government’” (https://www.history.com/topics/early-us/alien-and-sedition-acts).

Madison and Jefferson responded by saying, “[T]he several states who formed that instrument [the Constitution], being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to judge of its infraction; and that a nullification, by those [states], of all unauthorized acts….is the rightful remedy” (https://www.history.com/topics/early-us/alien-and-sedition-acts).

This battle between supporters of a strong central government and free expression still goes on today, though the terminology has changed. We now talk about misinformation rather than “scandalous and malicious writing.” But the principle of free speech has, so far, survived, along with the idea that each person should be the arbiter of right and wrong. This is important because it seems less and less likely that anyone can arbitrate between the two political parties.

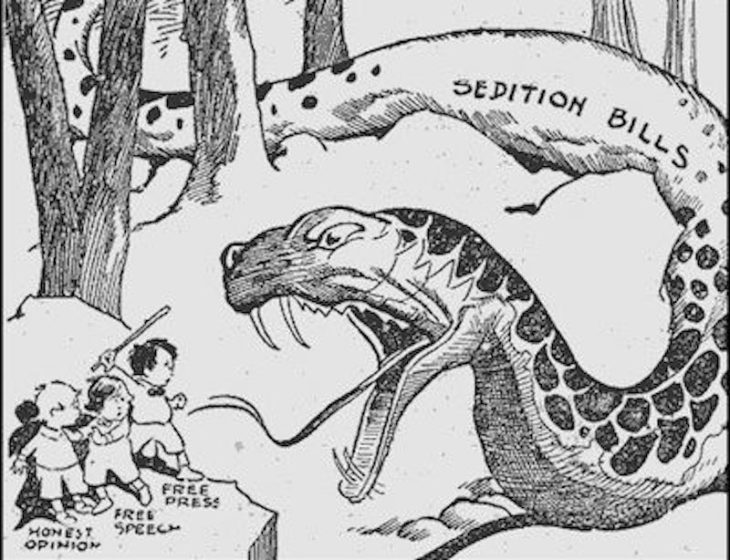

The image is of a political cartoon, labeled Satterfield of The Jersey City Journal, but I could not find out more about it. I assume that it is contemporary with the Alien and Seditions Act, but if not, you get the point.