Word of the Day: Scop

Today’s word of the day is scop, an Old English word referring to a person who makes up and recites poetry. Etymonline says this about scop: “cognate with Old High German scoph ‘poetry, sport, jest,’ Old Norse skop ‘railing, mockery’ from Proto-Germanic *skub-, *skuf- (source also of Old High German scoph ‘fiction, sport, jest, derision’), from PIE *skeubh- ‘to shove.’” In case you’re wondering, the English word scoff, to mock or speak derisively, is related to the word scop, but it did not come into English until the 14th century. And if you’re wondering, scop has no connection to scope, which comes from the Latin scopus, from the Greek skopos, but, in theory, from the PIE “*spek-yo-, suffixed form of root *spek- ‘to observe,’” with the transposition of the p and the k occurring through a process called metathesis. Just as a reminder, the asterisk before a word, like Proto-IndoEuropean (PIE) *skeubh-, means that it is a reconstructed word for which we do not have any written evidence.

The word comes to us today courtesy of Dr. Hana Videen. Videen, who has a Ph. D. in Old English from King’s College London, is a writer and blogger in Toronto, Canada, and she has been tweeting and blogging about Old English since 2013. Her website is called Word Hord, and she does an Old English Word of the Day on her website and her app, also called Word Hord. “Her book The Wordhord: Daily Life in Old English was published by Profile (2021) and Princeton University Press (2022)” (https://oldenglishwordhord.com/about/). She says, “The Old English word wordhord (word-hoard) describes the collection of words and phrases that a poet may draw upon while crafting tales. Unlike a dictionary or other physical book, this stockpile of verses and vocabulary exists only in the poet’s mind. Faced with the daunting task of reciting hundreds of lines of poetry, a storyteller would have certainly benefited from a well-stocked ‘hoard’ of words.” Of course, in contemporary English wordhord has been replaced by a word of Greek origin, lexicon.

At least one well-known writer, who actually preferred wordhord over lexicon, was John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, who was born on this date in 1892. Most of us know Tolkien as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but his life was much more than that. Tolkien was born in the Orange Free State (modern South Africa) though his parents were British. His father worked for a bank. When he was three, he, his mother, and his younger brother moved back to England, anticipating that his father would join him, but his father died of rheumatic fever.

From that point he grew up with family outside Birmingham, and it was countryside that he was able to explore, such as his aunt’s farm, called Bag End (if you’re familiar with The Hobbit, you know that name). His mother homeschooled him and his brother, and she got him started early in Latin, fostering a love of languages in him. She also converted to the Roman Catholic Church, against the objections of her family, leading to an estrangement that left her cut off, personally and financially.

Tolkien’s mother died at the relatively young age of 34, but there were no treatments for diabetes in her day. In her will, she made their guardian a Catholic priest, and he raised them. Tolkien added to his linguistic studies Old English. He also had his first exposure to a constructed language, through his cousins, Mary and Marjorie Incledon. He also participated in constructing a language with them and then constructing his own language. Then he went to Exeter College, Oxford, at first studying classics but then changing to English language and literature.

Tolkien was also involved in a real romance. He met Edith Mary Bratt when he was just 16 and she 19, but when the romantic interest was discovered, he was forbidden from seeing or communicating with her while he was still in his minority. When he turned 21, he wrote to her. She had recently become engaged to a friend of her brother, but she explained that she thought he had forgotten her. She ended her engagement married Tolkien.

Tolkien also served in WWI at the Battle of the Somme. After he finished at Oxford, he became an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, commanding enlisted men from working-class backgrounds. He got trench fever, an illness borne by lice, and was returned to England as an invalid, surviving the Battle of the Somme, but some of his childhood friends were not so lucky.

Many of the experiences he had as a young man later turned up in his fiction. One thing that also, in my opinion, appears in Tolkien’s fiction is his attitude toward command, John Garth, in his 2003 biography Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth, quotes Tolkien: “The most improper job of any man … is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity” (149). This is a truth we should trumpet every time there is a presidential election.

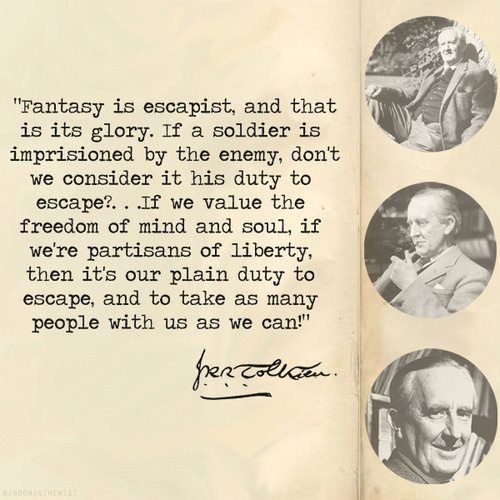

Today’s image is from QuoteGrams, and it shows a popular quotation from J. R. R. Tolkien. Except that Tolkien didn’t actually say it, no matter how many times it appears on Facebook or Pinterest. He did, however, in his speech/essay “On Fairie Stories,” say this:

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.