Word of the Day: Robot

Today’s word of the day is robot. A noun, robot means “a machine that resembles a human and does mechanical, routine tasks on command” or “a person who acts and responds in a mechanical, routine manner, usually subject to another’s will; automaton” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/robot). The second definition is a metaphor, as we discussed recently.

In this case, we know somewhat precisely when the word entered the language, “1923, ‘mechanical person,’ also ‘person whose work or activities are entirely mechanical,’ from the English translation of the 1920 play R.U.R. (‘Rossum’s Universal Robots’) by Karel Čapek (1890-1938), from Czech robotnik ‘forced worker,’ from robota ‘forced labor, compulsory service, drudgery,’ from robotiti ‘to work, drudge,’ from an Old Czech source akin to Old Church Slavonic rabota ‘servitude,’ from rabu ‘slave’ (from Old Slavic *orbu-, from PIE *orbh– ‘pass from one status to another;’ see orphan).

The Slavic word thus is a cousin to German Arbeit ‘work’ (Old High German arabeit). The play was enthusiastically received in New York from its Theatre Guild performance debut on Oct. 9, 1922. According to Rawson the word was popularized by Karel Čapek’s play, ‘but was coined by his brother Josef (the two often collaborated), who used it initially in a short story.’ Hence, ‘a human-like machine designed to carry out tasks like a human agent’” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=robot). So it really entered American English on October 9, 1922, though it undoubtedly took time to spread around the country.

On this date in 1921, Karel Čapek’s (1890-1938) R.U.R. premiered in Prague, Czechoslovakia. Prague is today the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic and centuries ago was the capital of the Kingdom of Bohemian. It is an ancient city with a rick culture, including theater, though Americans generally don’t know much about it. Part of the reason for our ignorance is the decades Czechoslovakia spent behind the Iron Curtain.

As I’m sure you have guessed, the play is science fiction. Sometime in the not-too-distant future, Rossum’s Universal Robots manufactures robots to provide various kinds of physical labor, both skilled and unskilled. But a woman leads a movement to improve the living conditions of these robots, who are made out of organic material but are not actually living. In response, the scientist in charge of the formula works on modifying it to make the robots even more human-like. Eventually, the robots are smarter and more numerous, and they rebel against their human masters. The result is the total destruction of humankind. Except that there is an epilogue in which a couple of the newest robots seem to have so much humanity in them that they may be a promise of the revival of the human race.

Here’s a fun fact: in the Theatre Guild production in 1923, at the Garrick Theatre in NYC, two of the robots were played by Spencer Tracy and Pat O’Brien.

Given the time when R.U.R. came out, one might think, and a lot of people have asserted, that the play is anti-capitalist and pro-communist. The big corporation turns out robots who do manual labor without complaint, creatures with no will and no soul. Eventually, these workers turn on their masters and destroy them all. Sounds like the revolution.

But the consequences of this revolution is not good. In the epilogue, we find out that the robots are doomed without the humans to continue producing them, except for, perhaps, the two young robots who may actually be human (in one production, these two, a male and a female, are actually holding a baby their arms). They have killed the scientist who was responsible for updating the robots.

In 1924, C wrote an essay entitled “Why I Am Not a Communist” in which he said, “The final word of Communism is to rule, not to save, its gigantic slogan is power [moc], not help [pomoc]. As Communism sees them, poverty, hunger, unemployment are not unbearable pain and shame but rather a welcome reservoir of dark powers, fermenting by lots of anger and resistance” (https://www.scribd.com/document/266965438/Karel-Čapek-Why-I-am-not-a-Communist). Čapek says that the solution to poverty is people, not government. R.U.R. is a actually a critique of communism rather than a call to revolution.

While Čapek introduced the word robot, one of the downsides of his play is that it created the model for robot stories for years to come. Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) criticized the play for setting up the formula of rebellious, evil robots who pose a threat to humankind. In fact, he wrote a series of stories about good robots, which he published in magazines in the 1940s. He wrote a frame story for those short stories and published them all together in I, Robot. He also wrote several novels with good robots as one of the main characters. And Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics are a response to the robots in R.U.R.

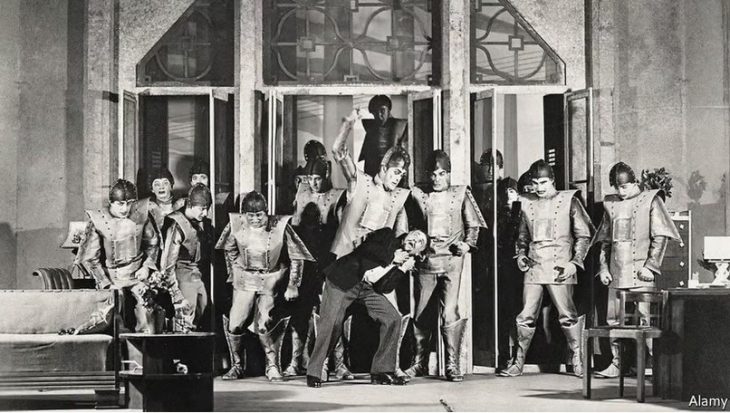

Today’s image is from a production of R.U.R., found in an article in The Economist (https://www.economist.com/prospero/2021/01/22/rur-foreshadowed-fears-about-artificial-intelligence). The fear of creatures with artificial intelligence apparently still exists.