Word of the Day: Bucolic

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Vocabulary.com, is bucolic. This adjective means “of or relating to shepherds” or “of, relating to, or suggesting an idyllic rural life” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/bucolic). The etymology looks like this: “’pastoral, relating to country life or the affairs and occupations of a shepherd,’ 1610s, earlier bucolical (1520s), from Latin bucolicus, from Greek boukolikos ‘pastoral, rustic,’ from boukolos ‘cowherd, herdsman,’ from bous ‘cow’ (from PIE root *gwou- ‘ox, bull, cow’) + -kolos ‘tending,’ related to Latin colere ‘to till (the ground), cultivate, dwell, inhabit’ (from PIE root *kwel- (1) ‘revolve, move round; sojourn, dwell’). Middle Irish búachaill, Welsh bugail ‘shepherd’ are Celtic words formed from the same root material as Greek boukolos” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=+bucolic).

I would love to know how “shepherd” comes from a PIE root that meant “cow, bull, ox,” but I’m sure it will come to me eventually.

Vocabulary.com says this about bucolic: “As an adjective, bucolic refers to an ideal country life that many yearn for. If your parents wanted to raise you in a bucolic environment, you may find yourself living 45 minutes away from the nearest movie theater or person your age. Not ideal” (https://www.vocabulary.com/word-of-the-day/).

In the history of the United States of America, the trend for people has been to move into urban areas. In 1790, right after the beginning of the country under the Constitution, most Americans lived in the country. According to the USDA, nine out of ten of the four million Americans lived on a farm (https://www.nass.usda.gov/About_NASS/History_of_Ag_Statistics/index.php). In 1890, when the population was almost 63 million, roughly 43% of the workforce worked on farms. In 2000, with the US population over 300 million, about 2 million people work and live on a farm, and another 1 million are hired farm laborers. Today, roughly 80% of Americans live in an urban environment.

One of the results of this change in the way Americans live is a longing for the simple life, the country life, the bucolic life. At least among some people. In the 1960s and ‘70s, these people would have been called hippies, but we might refer to them as Romantics.

The Romantic Movement in England began in the late 18th century as a response to the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment. It can be seen in literature, the visual arts, music, and even to a small extent leisure and lifestyle. Where the Enlightenment prioritized rational thinking and objectivity, the Romantics prioritized emotion and subjectivity. Where the Enlightenment prioritized society and the future, the Romantics prioritized the individual and the past. And where the Enlightenment preferred the improvement of nature through human art, the Romantics preferred nature.

While the Romantic Movement per se is given a time frame of 1780 to 1850, after which the movement called Realism followed, though a lot of scholars would start Realism in 1848, the year of the European Revolutions. Realism (and Naturalism) is followed by Modernism and Postmodernism. But the Romantic impulse did not die in 1850. It is still alive today, and is probably more popular in literature and mass media than Realism or the others.

This Romantic impulse is what drove hippies and others to form communes in the 1960s and ‘70s. The commune movement peaked in the late 1970s and declined after that, although there are still some communes around the country today. Did the Romantic impulse die?

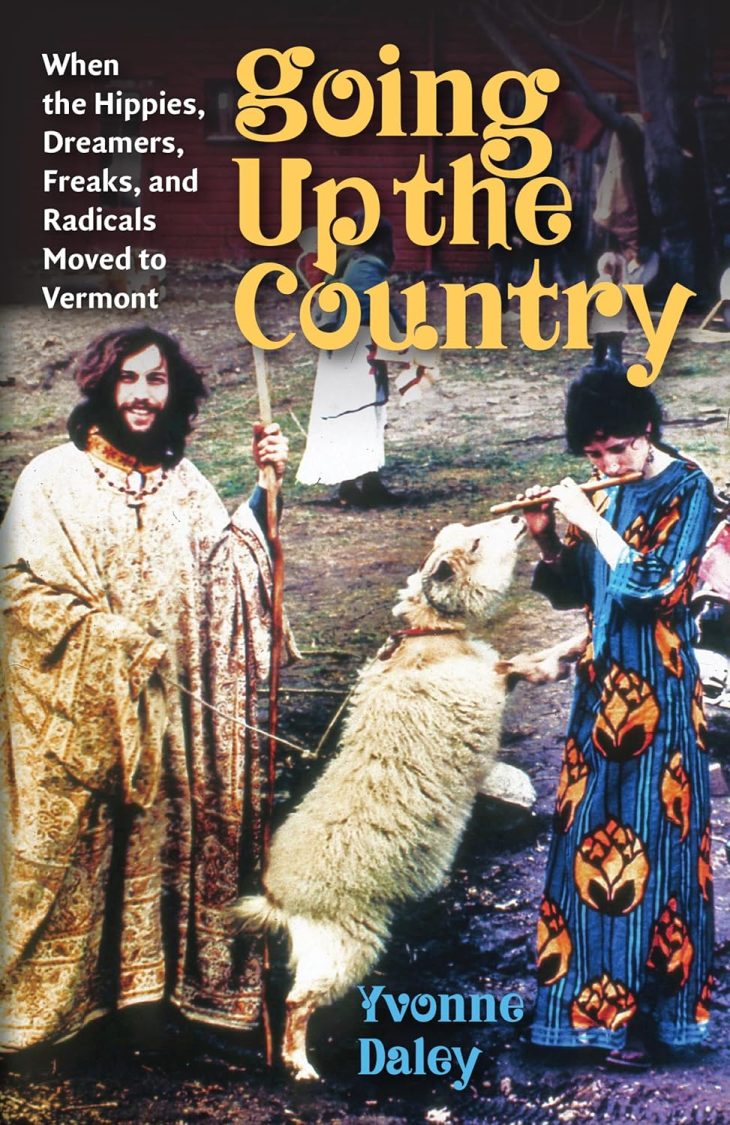

According to Yvonne Daley, who wrote Going Up the Country: When the Hippies, Dreamers, Freaks, and Radicals Moved to Vermont (Wesleyan UP, 2020), “As economic changes made living on next to nothing more difficult and as some early relationships broke up, many of the young people who had coupled up fell apart. Some moved back to where they had grown up or returned to college to finish degrees or get graduate ones. People with degrees began wanting to use those degrees for both economic and personal reasons. Despite their radical ideas, many people in this post-WWII generation had married, especially those who had children. With the breakup of marriages, some moved off of communes and to cities” (https://www.forbes.com/sites/russellflannery/2021/04/11/what-happened-to-americas-communes/?sh=26e1e1ac577a).

Today, according to Daley, communes are making a bit of a comeback, but they are more often called intentional communities: “The Foundation for Intentional Community’s directory says the number of communes, most referred to as intentional communities, nearly doubled between 2010 and 2016 (the last year the directory was published), to roughly 1,200. Although the number of people living in these communities is hard to pin down—the demographic is often deliberately off the grid—the foundation’s director Sky Blue estimated in 2020 that there are currently around 100,000 individuals residing in them. ‘There’s an obvious growth trend that you can chart,’ he said; millennials ‘get this intentional community thing more than people in the past.’”

The Forbes article also says that older Americans are migrating toward these intentional communities, but there is probably a difference. While both young and old may have the Romantic impulse to seek the pastoral lifestyle, the older Americans probably have their own means of financial support to carry them through any difficulties, and older couples have probably been together for many years and learned how to overcome obstacles. Younger participants probably lack those advantages.

One thing the hippies of the 1960s and the millennials of today may have discovered is that the rural, farming, living-off-the-land kind of life is not actually idyllic, though it may be bucolic. Of course, anyone who has read Shakespeare’s As You Like It, particularly Act 3, scene 2, the dialogue between Corin and Touchstone, knows that the shepherd’s life is not an easy one.

Today’s image is the cover of the Yvonne Daley’s book, which features an ideal of the country life.