Word of the Day: Inanity

Today’s word of the day, thanks to the NY Times, is inanity. The Times defines inanity as “a total lack of meaning, significance or substance” (https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/04/learning/word-of-the-day-inanity.html). Dictionary.com defines the noun as “lack of sense, significance, or ideas; silliness” or “something inane” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/inanity). If you’re like me, you may find the circular definition of a word a bit annoying. You might wonder why I didn’t just make the word of the day inane.

To answer, I’ll refer to the word’s etymology: the word entered the language “c. 1600, ‘emptiness, hollowness,’ literal and figurative, from French inanité (14c.) or directly from Latin inanitas ‘emptiness, empty space,’ figuratively ‘worthlessness,’ noun of quality from inanis ‘empty, void; worthless, useless,’ a word of uncertain origin. De Vaan writes that ‘The chronology of attestations suggests that “empty, devoid of” is older than “hollow.”’ Meaning ‘silliness, want of intelligence’ is from 1753” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=inanity). However, the etymology of inane says that it entered the language “1660s, ‘empty, void,’ from Latin inanis or else a back-formation from inanity (q.v.).” [“Q.v.” is an abbreviation for the Latin quod vide, “which see,” a phrase intended to direct the reader to another page to learn something further; in this case, you’re supposed to click on the hyperlinked word to learn more.]

So inane is very possibly a backformation from inanity, an adjective derived from the noun by removing what looks like a suffix.

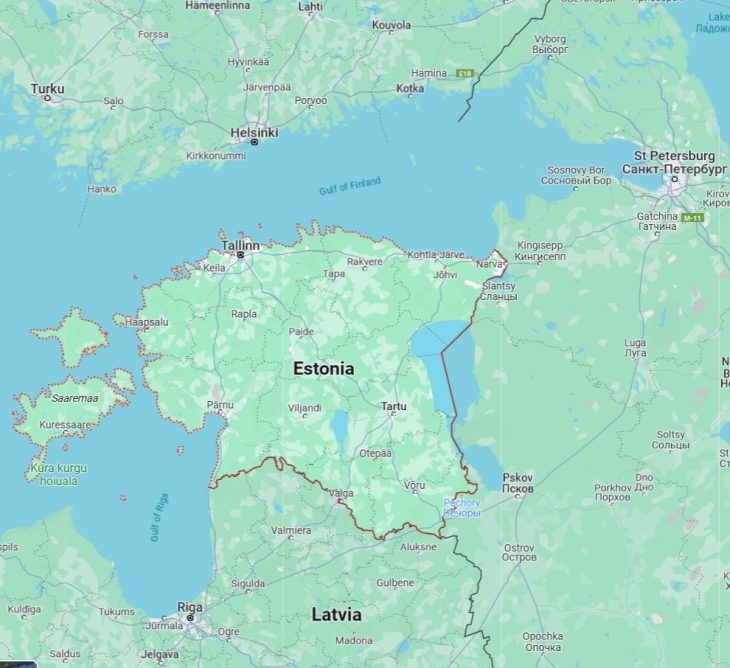

Today I learned, from a podcast, a little about Estonia. Estonia is a Baltic country, in northern Europe, bordered on the south by Latvia, on the east by Russia, and on the north by and west by the Baltic Sea. For most of its existence, it has not been a country of its own. In the 20th century, it had only a few years of being its own country. For much of its recent history, it has been a victim of wars by Sweden, Poland, Finland, and Russia. In 1710, Russia conquered the whole of Estonia, and it held it until the twentieth century.

The Russians tried to make Estonia more Russian by requiring that the Russian language be used in schools and in government business. In 1918, very briefly, Estonia declared its independence from Russia, but then the Germans invaded. After World War had concluded, the Germans were forced to give control back to the Estonian provincial government But the Soviet Union invaded Estonia leading to the War of Estonian Independence, which Estonia won. The new nation joined the League of Nations and formed treaties with Germany and the Soviet Union in the 1930s, but eventually it was victimized again.

In 1939, in the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany agreed to split up northern Europe into spheres of influence. Estonia was given to the Soviet Union. The Soviets turned Estonia into the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, depriving it on nationhood. They also tried to impose socialism on the Estonians, who until then had a relatively good standard of living. Unfortunately, the Estonians did not always cooperate. Many were sent to Siberia, and the standard of living for those who remained declined.

Finally, in the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union was collapsing, Estonia began protesting, demanding its independence, along with its neighbors, Latvia and Lithuania. The Singing Revolution was based upon patriotic songs. The Baltic Way was a demonstration of close to 2 million people through the three small countries. Finally, Estonia was free.

Then, in 1992, Estonia elected their first truly independent parliament, and the prime minister was a young radical named Mart Laar. Laar has said that he came across the name Milton Friedman in Soviet propaganda, mentioned there as an evil capitalist economist. Laar read Friedman’s works because he assumed that if the Soviets though he was bad, then he must be good. Laar though Friedman was just a solid economist.

As prime minister, Laar realized that he needed to, as Margaret Thatcher had said, “just do it.” He privatized most of the industries that the Soviets had socialized. He tied the Estonian currency to the Deutsche Mark. He instituted the world’s first national flat tax. And he declared unilateral free trade. He took the free-market principles espoused by Milton Friedman and applied them in a national experiment, against the advice of the International Monetary Fund.

What was the result? Today Estonia is 31st (out of 66 nations) on the UN’s Human Development Index. It is a national leader in the use of technology, being the first country to allow voting over the internet. It is 36th (out of 179) in per capita GDP. In 2020, it ranked 3rd in the Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index. Estonia’s transition from a communist economy to a free-market economy happened faster and more smoothly than just about any other former soviet country.

The story of Estonia’s rapid rise in terms of freedom and wealth is remarkable. It is told in The Road to Freedom: Estonia’s Rise from Soviet Vassal State to One of the Freest Nations on Earth, by Matthew D. Mitchell, Peter J. Boettke, and Konstantin Zhukov.

Estonia’s rise as a nation is worth considering in our country, where, according to polls, a majority of people in their 20s and 30s believe that socialism is a better economic system than free-market capitalism. Admittedly, the USA no longer has a system of free-market capitalism as the government is far more involved in the economy than ever before. But Estonia’s story is a good counter to the inanity of socialism.

I hope to visit Estonia. It looks like a beautiful place.

Today’s image is a map of modern Estonia (https://www.google.com/maps/place/Estonia/@58.670608,24.9321194,7z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m6!3m5!1s0x4692949c82a04bfd:0x40ea9fba4fb425c3!8m2!3d58.595272!4d25.0136071!16zL20vMDJrbW0?entry=ttu).