Word of the Day: Disparage

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Word Guru, is disparage. This verb means “to speak of or treat slightingly; depreciate; belittle” or “to bring reproach or discredit upon; lower the estimation of” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/disparage).

The word entered English in the “late 14c., ‘degrade socially’ (for marrying below rank or without proper ceremony), from Anglo-French and Old French desparagier (Modern French déparager) ‘reduce in rank, degrade, devalue, depreciate,’ originally ‘to marry unequally, marry to one of inferior condition or rank,’ and thus, by extension, to bring on oneself or one’s family the disgrace or dishonor involved in this, from des- ‘away’ (see dis-) + parage ‘rank, lineage’ (see peer (n.)).

“Also from late 14c. as ‘injure or dishonor by a comparison,’ especially by treating as equal or inferior to what is of less dignity, importance, or value. Sense of ‘belittle, undervalue, criticize or censure unjustly’ is by 1530s” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=disparage).

We have another example of broadening.

According to On This Day, on this date in 1633, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) arrived in Rome for his second heresy trial.

Il processo a Galileo Galilei (The trial of Galileo Galilei, or the Galileo Affair) actually began over two decades earlier, in 1610, when Galileo published an treatise called “Starry Messenger,” based upon his observations with the telescope he had made, based upon the first telescope that had been invented just a couple of years earlier. Based upon his observations, he supported the Copernican theory of the heliocentric (sun-centered) universe, as opposed to the geocentric universe of Ptolemy and Aristotle.

A lot of Protestants objected to Copernicus’s argument in the 16th century, but the Roman Catholic Church seemed to accept it, with a few exceptions. But in the early 17th century, philosophers and theologians in the Catholic Church began to speak out against it, just in time for Galileo to support it. So in 1616, the Church put Galileo on trial for heresy. On February 24, 1616, a commission of theologians announced to Galileo that the Copernican theory was “foolish and absurd” as well as “heretical” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_affair). Two days later, Galileo was told “to abstain completely from teaching or defending this doctrine and opinion or from discussing it… to abandon completely… the opinion that the sun stands still at the center of the world and the earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing” (ibid.).

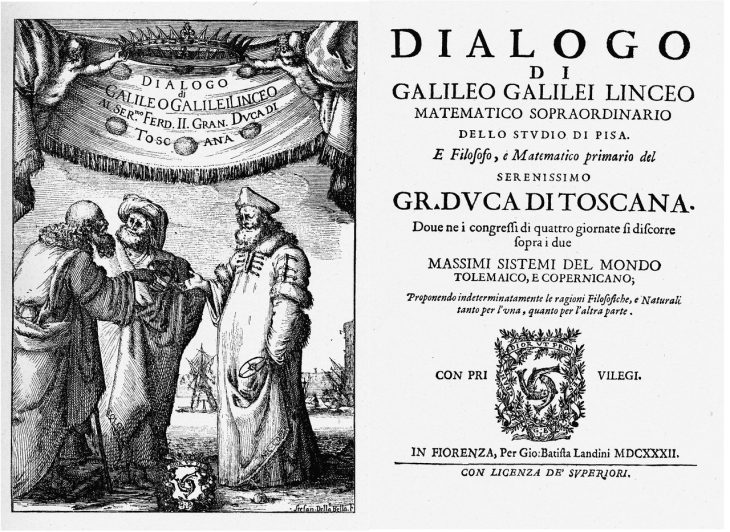

But then, in 1632, Galileo published Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems), a book that compared the Copernican view of the universe with that of Ptolemy. The defender of the Ptolemaic system, named Simplicio, was presented as not very bright. He was refuted and even mocked by Salviati, the defender of the Copernican system. Sagredo is a layman who is initially neutral but ends up on the side of Salviati.

Pope Urban VIII, who had become pope in 1623, was initially warm towards Galileo, but he did not like the Dialog. In fact, some of Galileo’s detractors convinced Urban that Simplicio was actually an unfavorable portrait of Urban. The Pope banned the sale of the Dialog and submitted it to examination by a commission.

As a result of the publication of the Dialog, “Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy ‘for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world’ against the 1616 condemnation, since ‘it was decided at the Holy Congregation […] on 25 Feb 1616 that […] the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned’” (ibid.). And imprisoned he was, sort of. Today we would call it being put under house arrest, and he stayed under house arrest for the rest of his life. Furthermore, his publications, past, present, and future, were banned.

Despite the ban on future publications, Galileo published Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze (Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences) in Holland, after being unable to publish it in several other countries. He used the same three character names, but the nature of the characters was different. Simplicio was Galileo when he was young, Sagredo in the middle of his life, and Salviati as an older man. The two sciences were strength of materials and motion, with more time spent on the latter topic.

In the Two New Sciences, Galileo wrote, “This and other facts, not few in number or less worth knowing, I have succeeded in proving; and what I consider more important, there have been opened up to this vast and most excellent science, of which my work is merely the beginning, ways and means by which other minds more acute than mine will explore its remote corners” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei).

Galileo Galilei’s reputation was disparaged by the Roman Catholic Church and by all the scholars who refused to look at the actual evidence with an open mind. Fortunately, in the long run, the evidence won out.

Today’s image is the “Frontispiece and title page of Galileo’s Dialogue, in which Galileo advocated heliocentrism” (printed by Giovanni Battista Landini) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_affair).