Word of the Day: Divest

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of the Word Guru email (their word was divestiture), is divest. Divest is a verb that means to “to strip of clothing, ornament, etc.,” “to strip or deprive (someone or something), especially of property or rights,” “to rid of or free from,” “to take away or alienate (property, rights, etc.)”—a definition related to the law, “to sell off,” or “to rid of through sale” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/divest). The last two definitions relate to business or commerce.

The word first appears in the language in the “1560s, deves (modern spelling is c. 1600), ‘strip of possessions,’ from French devester ‘strip of possessions’ (Old French desvestir), from des- ‘away’ (see dis-) + vestir ‘to clothe,’ from Latin vestire ‘to clothe’ (from PIE *wes- (2) ‘to clothe,’ extended form of root *eu- ‘to dress’).

“The etymological sense of ‘strip of clothes, arms, or equipage’ is from 1580s. Meaning ‘strip by some definite or legal process’ is from 1570s. Economic sense ‘sell off’ (a subsidiary company, later an investment) is by 1961” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=divest).

You can probably see the English word vest in divest, and the etymology makes the link clear: *eu is the “Proto-Indo-European root meaning ‘to dress,’ with extended form *wes- (2) ‘to clothe.’

“It forms all or part of: divest; exuviae; invest; revetment; transvestite; travesty; vest; vestry; wear.

“It is the hypothetical source of/evidence for its existence is provided by: Hittite washshush ‘garments,’ washanzi ’they dress;’ Sanskrit vaste ‘he puts on,’ vasanam ‘garment;’ Avestan vah-; Greek esthes ‘clothing,’ hennymi ‘to clothe,’ eima ‘garment;’ Latin vestire ‘to clothe;’ Welsh gwisgo, Breton gwiska; Old English werian ‘to clothe, put on, cover up,’ wæstling ‘sheet, blanket’” (ibid.). Just FYI, exuviae means “the cast skins, shells, or other coverings of animals” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/exuviae). And revetment means “a facing of masonry or the like, especially for protecting an embankment” or “an ornamental facing, as on a common masonry wall, of marble, face brick, tiles, etc.” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/revetment).

On this date in 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey premiered at the Uptown Theatre in Washington, D.C. It opened in New York the next day and in Los Angeles the following.

Arthur C. Clarke, one of the great science fiction writers of the Golden Age of Science Fiction (per Robert Silverberg), along with Asimov, Bradbury, Heinlein, and Philip K. Dick (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Age_of_Science_Fiction)., published a short story in 1951 entitled “The Sentinel.” It’s a simple story: people find a pyramid type thing on the Moon, surrounded by a force field. It takes people 20 years to break through the force field, but the structure stays a mystery. The scientists come to believe that it was left there by aliens, and that is how the story ends.

Clarke later expressed contempt for the idea that 2001 was based the story, saying, “I am continually annoyed by careless references to “The Sentinel” as “the story on which 2001 is based”; it bears about as much relation to the movie as an acorn to the resultant full-grown oak” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sentinel_(short_story)). But the story was the germ from which the movie grew.

Stanley Kubrick, who directed the film, was the one who came up with the idea for a realistic space travel film. He had already made a deal with a studio and had already planned where to do the filming. With the general idea, Kubrick went looking for a collaborator, someone with a science fiction background, and a friend recommended Clarke. Starting with “The Sentinel,” Clarke and Kubrick added plot elements from others of Clarke’s stories and added additional ideas. This was how they developed the script for 2001: A Space Odyssey, although at the same time they were developing a novel. The collaboration was complex and at times difficult, but it worked.

The film’s reception was somewhat mixed, and after the opening, Kubrick and his editor trimmed the film some. But it is a different kind of film, and people either love it or hate it. It takes advantage of classical music and long periods during which there is no dialogue. The visuals and the special effects are wonderful and occupied a lot of the director’s time and effort.

The movie was nominated for four Academy Awards, and it won for Best Visual Effects. It was also nominated for other awards, and it won some.

I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey when I was a kid. I found it fascinating though I probably didn’t really understand it. Of course, I’m not sure anybody really understood it. There have been many interpretations of various parts of the movie, the monolith, the “Star Child,” HAL, and other things. Even reading the novel, which came out shortly after the movie and which tried to be more explanatory, does solve all the riddles.

But the movie did well enough with audiences, for whatever reason, that it eventually became the highest grossing film of 1968 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2001:_A_Space_Odyssey#Design_and_special_effects). It would have been a movie worth investing in.

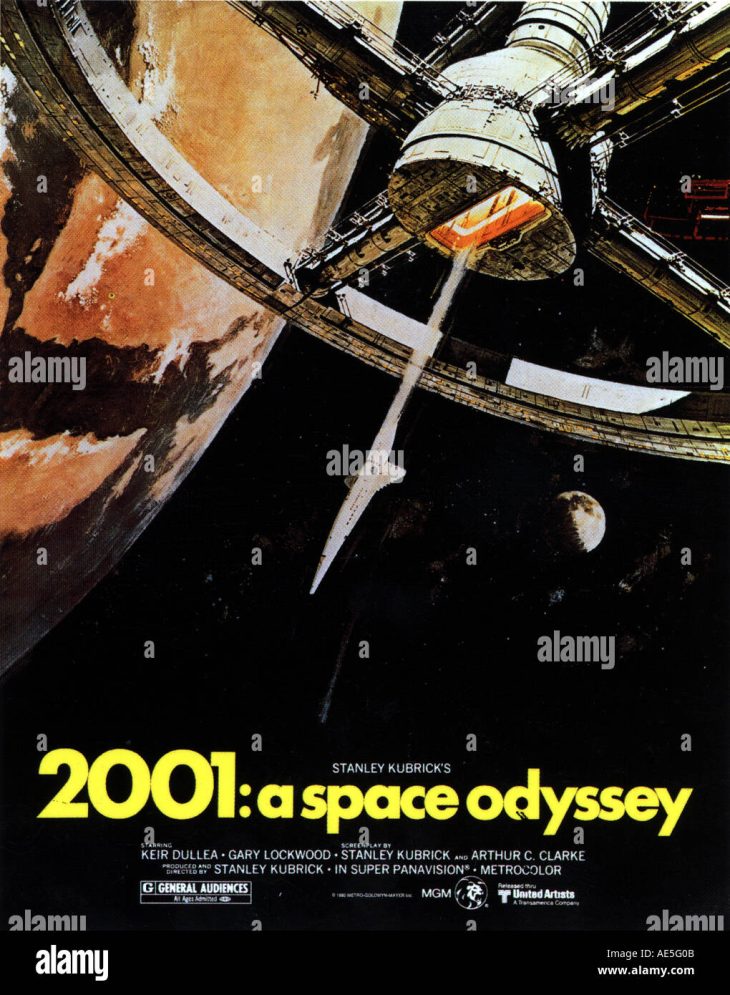

Today’s image is of a poster for the original release of 2001: A Space Odyssey. If you have never seen it, you should, though it loses something on a small screen and without surround sound.