Word of the Day: Cohesive

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Merriam-Webster, is cohesive. Cohesive is an adjective that means “tending to cohere; well-integrated; unified” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/cohesive). This is one of those definitions which is kind of annoying because you really have to go to the word cohere to get a real sense of what it means. The verb cohere means “to stick together; be united; hold fast, as parts of the same mass” or “to be naturally or logically connected” or “to agree; be congruous” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/cohere).

Merriam-Webster’s definition is this: “Something described as cohesive sticks together and forms something closely united. The word is usually used with abstract terms in phrases like “a cohesive social unit” or “a cohesive look/aesthetic.” Cohesive can also be used to describe something, such as the design of a room or the plot of a movie, that is coherent—in other words, logically or consistently ordered” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-of-the-day). M-W adds, “The Latin verb haerēre has shown remarkable stick-to-itiveness in influencing the English lexicon, which is fitting for a word that means ‘to be closely attached; to stick.’ Among its descendants are adhere (literally meaning ‘to stick’), adhere’s relative adhesive (a word for sticky substances), inhere (meaning ‘to belong by nature or habit’), and even hesitate (which implies remaining stuck in place before taking action). In Latin, haerēre teamed up with the prefix co- to form cohaerēre, which means ‘to stick together.’ Cohaerēre is the ancestor of cohesive, a word borrowed into English in the early 18th century to describe something that sticks together literally (such as dough or mud) or figuratively (such as a society or sports team).”

The etymology webpage says that it entered the language in “1730, with -ive + Latin cohaes-, past participle stem of cohaerere ‘to cleave together,’ in transferred use, ‘be coherent or consistent,’ from assimilated form of com ‘together’ (see co-) + haerere ‘to adhere, stick’” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=cohesive). But the same webpage also points out that the noun cohesion, which has nearly the same etymology, came into the language in the 1670s, making one wonder if perhaps the adjective was formed from the noun rather than being borrowed. The difference is that cohesion was borrowed “from French cohsion, from Latin cohaesionem (nominative cohaesio).”

On this date in 1753 in Stockholm, Sweden, Laurentius Salvius published a book written by Carl Linnaeus entitled Species Plantarum (The Species of Plants), in two volumes. The book “lists every species of plant known at the time, classified into genera. It is the first work to consistently apply binomial names and was the starting point for the naming of plants” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Species_Plantarum).

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was born in a village in southern Sweden to a Lutheran minister and curate who taught him Latin when he was just a boy. He had several siblings, one of whom, a younger brother, wrote a manual on beekeeping and was also a curate. Carl’s father had adopted the surname Linnaeus (actually Linnæus, the Latin form of the name of a tree) because the University of Lund required him to do so; prior to that, members of the family used the patronymic, as is still used in Iceland today; he was the first generation of his family to have a surname (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus).

From early years, Carl Linnæus was interested in plants. When he went off to grammar school, he often skipped studying in order to be outside, observing plants. Hearing negative opinions from the teachers at the grammar school, Carl’s father decided to apprentice him to a cobbler (a shoe maker). But in his last year at the grammar school, he studied with the headmaster, Daniel Lannerus, who noticed his interest in plants. Lannerus “gave him the run of his garden. He also introduced him to Johan Rothman, the state doctor of Småland and a teacher at Katedralskolan (a gymnasium) in Växjö. Also a botanist, Rothman broadened Linnaeus’s interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus). [Nota bene: a gymnasium in Germanic countries is like a high school that prepares students for higher education, or like what in the USA is called a preparatory school.]

Linnæus study first at Lund and then at the University of Uppsala. He studied previous botanists, such as Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708), who had published a book on the classification of plants, dividing plants into species and genera. He continued his studies until he had earned a doctorate, and he traveled around the Scandinavian countries studying plants.

In 1735, he published a work of classification entitled Systema Naturæ, which introduced what became known as the system of binomial nomenclature (two-term naming system). That work came out in multiple editions over the years. “The full title of the 10th edition (1758), which was the most important one, was Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, which appeared in English in 1806 with the title: “A General System of Nature, Through the Three Grand Kingdoms of Animals, Vegetables, and Minerals, Systematically Divided Into their Several Classes, Orders, Genera, Species, and Varieties, with their Habitations, Manners, Economy, Structure and Pecularities” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systema_Naturae).

Then he published Species Plantarum and made his biggest splash: “The book contained 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes; it described over 7,300 species. The same year the king dubbed him knight of the Order of the Polar Star, the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight in this order. He was then seldom seen not wearing the order’s insignia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus).

Binomial nomenclature, despite the oddity of insisting on using Latin forms of words, does provide a cohesive structure to the classification of plant life, so much so that the publication of Species Plantarum is often considered the beginnings of modern botany. It is, I hope, instructive that the man who developed this system would never have done so had he been forced to be a cobbler.

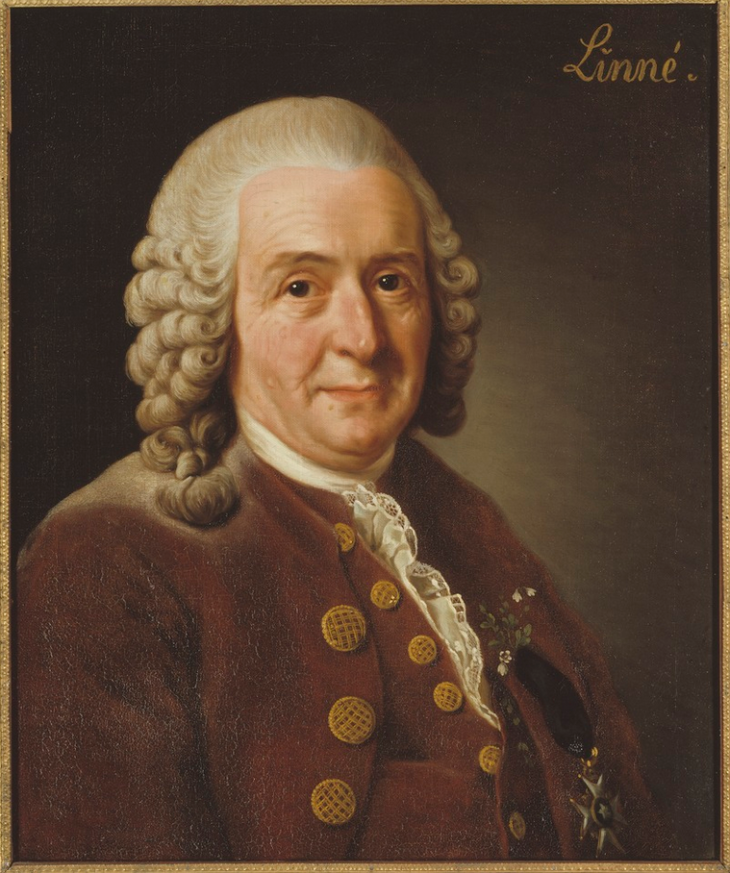

Today’s image is of Carl Linnæus, whose name was changed to von Linne when he was given a title. The portrait was by Alexander Roslin, and it is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus#/media/File:Carl_von_Linn%C3%A9,_1707-1778,_botanist,_professor_(Alexander_Roslin)_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15723.tif). He looks like a happy person.