Word of the Day: Galvanic

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of Wordsmith’s “A Word A Day” email, is galvanic. The –ic suffix should make it clear that galvanic is an adjective. According to the Wordsmith, it means, “Stimulating; energizing; shocking” and “Relating to electric current, especially direct current.” Dictionary.com lists the first definition as their third definition: “pertaining to or produced by galvanism; producing or caused by an electric current,” and “affecting or affected as if by galvanism; startling; shocking” and “stimulating; energizing” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/galvanic). The first two definitions are those generally annoying kind that require one to look up another word, but in this case doing so leads directly to the etymology.

So the adjective galvanic is derived from the noun galvanism. According to Etymology.com, it entered the language in 1797, “see galvanism + -ic. Perhaps from or based on French galvanique” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=galvanic). Galvanism also entered the language in 1797, “’electricity produced by chemical action,’ 1797, from French galvanisme or Italian galvanismo, from Luigi Galvani (1737-1798), professor of anatomy at Bologna, who discovered it c. 1792 while running currents through the legs of dead frogs” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/galvanism).

Merriam-Webster gives this under Word History: “The French words galvanisme and galvanizer were apparently introduced by Alexander von HUMBOLDT in a letter, dated January 24, 1796 (‘Lettre de F. Humboldt à M. Pictet … sur lʼinfluence de lʼacide muriatique oxygené et sur lʼirritabilité de la fibre organisée, lue a lʼInstitut national’), published in the Magasin encyclopédique, ou Journal des sciences, des lettres et des arts (Lʼan quatrième [1795],) pp. 462-72. In a footnote Humboldt states ‘Les mots de galvanisme, galvaniser, dont je me sert, sont formés dʼaprès ceux de magnétisme, magnétiser. Ils sont recommendables pour sa briéveté.’ (‘The words galvanism, galvanize, which I make use of, are modeled on magnetism, magnetize. They are commendable for their conciseness’)” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/galvanism).

When I was in college and grad school, I had to read articles from pretty old journals that would include quotations from German, French, Latin, and Greek, and the authors wouldn’t translate them for the reader. It was like they were expecting everyone to have a reading knowledge of multiple languages, and maybe we should have had. But it was a bit annoying because if you didn’t have a reading knowledge of the quoted language, you had to find a classmate who did and would translate the passage for you. But today we have Google Translate, so I’m going to quote the title of the letter for you, starting with “sur”: “on the influence of oxygenated muriatic acid and on the irritability of organized fiber, read at the National Institute.” The publication’s translation awkwardly reads, “Encyclopedic magazine, or Journal of sciences, letters and arts (Lʼan fourth).” I assume that last thing means the fourth edition. And if you’re not familiar with higher education, please understand that a “letter” is not necessarily a letter to the editor; it’s just a shorter paper.

Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) was born in Bologna to a goldsmith (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Galvani). He attended the University of Bologna and studied medicine, as his father wanted him to (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Luigi-Galvani). “On obtaining the doctor of medicine degree, with a thesis (1762) De ossibus on the formation and development of bones, he was appointed lecturer in anatomy at the University of Bologna and professor of obstetrics at the separate Institute of Arts and Sciences” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Luigi-Galvani).

As a professor, he both taught and did research, and his research began to focus on electrophysiology: “Numerous ingenious observations and experiments have been credited to him; in 1786, for example, he obtained muscular contraction in a frog by touching its nerves with a pair of scissors during an electrical storm. Again, a visitor to his laboratory caused the legs of a skinned frog to kick when a scalpel touched a lumbar nerve of the animal while an electrical machine was activated. Galvani assured himself by further experiments that the twitching was, in fact, related to the electrical action” (ibid.).

His experiments led to his conclusion that “animal electricity” was a force in animals that caused the firing of muscles. He briefly faced a bit of controversy when Alessandro Volta, professor of physics at the University of Pavia, disputed the results, suggesting an alternative theory as to why the dead frog’s muscles twitched when contracted by metal, but Galvani showed through more experiments that his theory was indeed on target. But the disagreement was an amicable one, and it was Volta who coined the word galvanism (ibid.).

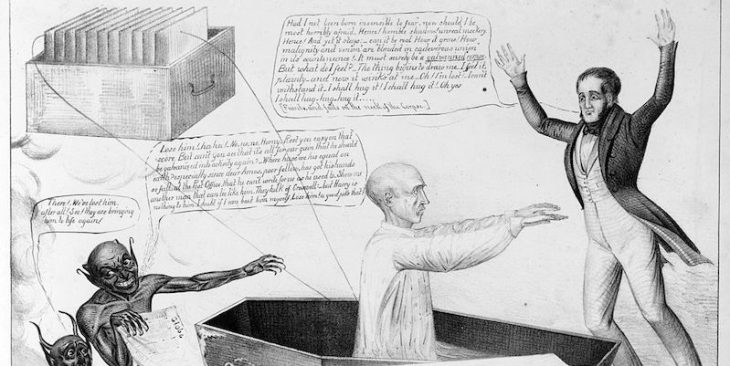

Mary Shelley made reference to galvanism in her 1818 novella Frankenstein, which, as you probably recalled, involved the re-animation of dead human body parts into a human monster. Frankenstein accomplished this feat using electricity to bring his monster to life. Sadly, no amount of galvanic activity by scientists over the last 200 years has been able to replicate Frankenstein’s results.

Today’s image is from an article by Timothy Jorgensen (https://lithub.com/the-italian-electrical-scientist-who-may-have-inspired-frankenstein/).