Word of the Day: Allay

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of the Dictionary Project email, is allay. According to the email, allay was at one point a noun meaning “a calming, soothing force,” and it provides this sentence as an example: “Friendship is the allay of our sorrows, the ease of our passions, the discharge of our oppressions, the sanctuary to our calamities, the counselor of our doubts, the clarity of our minds (Jeremy Taylor 1613-1667).” But it is used today as a transitive verb meaning “to calm; to appease; to pacify” or “to lessen; to alleviate.”

Merriam-Webster suggests that there was an intransitive verb meaning “to diminish in strength,” but M-W labels that meaning “obsolete” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/allay).

The word goes back through “Middle English alegen, from Old English alecgan ‘to put, place, put down; remit, give up, suppress, abolish; diminish, lessen,’ from a- ‘down, aside’ (see a- (1)) + lecgan ‘to lay’ (see lay (v.)). A common Germanic compound (cognates: Gothic uslagjan ‘lay down,’ Old High German irleccan, German erlegen ‘to bring down’).

“Early Middle English pronunciations of -y- and -g- were not always distinct, and the word was confused in Middle English with various senses of Romanic-derived alloy (v.) and especially a now-obsolete verb allege “to alleviate, lighten” (from Latin alleviare, from ad ‘to’ + levis ‘light’ in weight; from PIE root *legwh- ‘not heavy, having little weight’).

“Amid the overlapping of meanings that thus arose, there was developed a perplexing network of uses of allay and allege, that belong entirely to no one of the original vbs., but combine the senses of two or more of them. [OED]

“Hence the senses ‘lighten, alleviate; mix, temper, weaken.’ The confusion with the Latin words probably also accounts for the unetymological double -l-, attested from 17c.” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=allay).

On this date 313 years ago, An Essay on Criticism was published anonymously. The poem, as it turned out, was the first major work of the 18th century NeoClassical poet Alexander Pope.

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) was born in London to a linen merchant; both of his parents were Roman Catholics, and given that he was born in the year of the Glorious (or Bloodless) Revolution, that drove the Catholic James II from office, their faith was a problem. The family moved from London to Popeswood, Binfield, Berkshire because Catholics were not allowed to live within 10 miles of London (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Pope). From that point on, he was an autodidact, reading the classical writers like Horace, Virgil, and Juvenal as well as English authors like Chaucer, Shakespeare, and John Dryden.

In addition to having to deal with discrimination due to his faith, Pope also suffered health problems, particularly “Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine, which deformed his body and stunted his growth, leaving him with a severe hunchback. His tuberculosis infection caused other health problems including respiratory difficulties, high fevers, inflamed eyes and abdominal pain. He grew to a height of only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres)” (ibid.). Later in his life, when his writing had made him some enemies, he was often ridiculed for his size and deformity, even being depicted in a cartoon as a monkey.

The Essay on Criticism was begun in 1707, when Pope was just 19. He published it when he was 23—pretty audacious given the content. It is a satire in the mode of Horace, and it is written in heroic couplets—rhymed pairs of lines in iambic pentameter. The iambic pentameter line had been in use for well over 100 years when Pope employed it. The line has been called “[Christopher] Marlowe’s Mighty Line,” and Shakespeare used it in both his poetry and his plays. But Pope employed it almost all the time, and while many poets might see the strict adherence to the heroic couplet as a straightjacket, Pope was able to use it with amazing flexibility.

The content was about literature, what was good and what was not good: “The ‘essay’ begins with a discussion of the standard rules that govern poetry, by which a critic passes judgement. Pope comments on the classical authors who dealt with such standards and the authority he believed should be accredited to them. He discusses the laws to which a critic should adhere while analysing poetry, pointing out the important function critics perform in aiding poets with their works, as opposed to simply attacking them. The final section of An Essay on Criticism discusses the moral qualities and virtues inherent in an ideal critic, whom Pope claims is also the ideal man” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Pope).

There are a number of famous lines from An Essay on Criticism.

“To err is human, to forgive, divine” (https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/242522-an-essay-on-criticism).

“Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.”

“A little learning is a dangerous thing.

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring;

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

and drinking largely sobers us again.”

And my favorite, “True Wit is Nature to advantage dress’d

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d;

Something whose truth convinced at sight we find,

That gives us back the image of our mind.

As shades more sweetly recommend the light,

So modest plainness sets off sprightly wit” (ibid.).

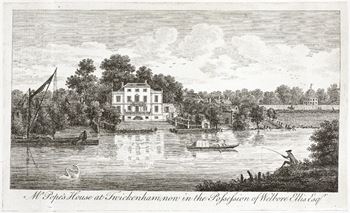

Today’s image is of Alexander Pope’s mansion, called Twickenham. Despite the prejudice against him because of his being Roman Catholic, and despite his health problems and the ridicule he faced because of it, Pope became quite wealthy. His wealth derived from his poetry, particularly from his translations of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. I would have conclude by saying that if you are a poet and are hoping that your poetry will make you wealthy, as Pope’s did, I firmly believe nothing allay your disappointment.