Word of the Day: Concatenate

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Vocabulary.com, is concatenate (https://www.vocabulary.com/word-of-the-day/). Concatenate is a verb that means “to link together; unite in a series or chain” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/concatenate). Merriam-Webster says, “Concatenate is a fancy word for a simple thing: it means ‘to link together in a series or chain.’ It’s Latin in origin, formed from a word combining con-, meaning ‘with’ or ‘together,’ and catena, meaning ‘chain.’ (The word chain is also linked directly to catena.) Concatenate can also function in English as an adjective meaning ‘linked together,’ as in ‘concatenate strings of characters,’ but it’s rare beyond technology contexts. More common than either concatenate is the noun concatenation, used for a group of things linked together in a series, as in ‘a concatenation of events led to the mayor’s resignation’” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/concatenate).

The word entered the English language in the “1590s, from Late Latin concatenatus, past participle of concatenare ‘to link together,’ from com ‘with, together’ (see con-) + catenare, from catena ‘a chain’ (see chain (n.)) (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=concatenate). Concatenation entered the language around 1600 (ibid.). Com-, con-, and co-, when used as prefixes in words ultimately derived from Latin, are all basically the same. The difference depends upon the sound that immediately follows the prefix.

On this date in 1959, Japanese Americans who had been interned in concentration camps in 1942 and then deprived of their citizenship were given the opportunity to reclaim it.

On December 7, 1941, of course, the Japanese military bombed the US Naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawai’i. For a lot of people, that is the beginning of World War II. For others, World War II began in 1939, when the Germans invaded Poland. But in reality, it had started much earlier, especially in Asia. Almost 8 years earlier, Japan invaded Manchuria, setting off a war that eventually led to Pearl Harbor.

In 1936, Germany and Japan formed an alliance against the Soviet Union and the international communist movement. In 1937, Japan invaded China, and a few months later, Italy joined in the Anti-Comintern Pact.

While the Japanese had conquered Manchuria, they struggled with China. Part of the problem was the lack of natural resources; Japan had only 6% of the oil it needed for domestic use and its international aspirations (https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/why-did-japan-attack-pearl-harbor#:~:text=The%20Japanese%20decided%20then%20that,the%20Pacific%20and%20Southeast%20Asia.). The Japanese were trying to create their own empire in Asia, one to rival the dreams of Hitler and the Nazis.

In 1940, Japan invaded French Indochina. France had colonized a large part of Southeast Asia in the nineteenth century, But China was able to import arms and other materiel through Indochina, so the Japanese invaded despite the fact that in 1940 France was run by a puppet regime, called Vichy France (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_invasion_of_French_Indochina). Initially, the Japanese apologized for the intrusion on France’s sovereignty, but in 1941, they invaded again. In response to the occupation of French Indochina, the United States “retaliated by freezing all Japanese assets in the states, preventing Japan from purchasing oil. Having lost 94% of its oil supply and unwilling to submit to U.S demands, Japan planned to take the oil needed by force. However, striking south into British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies would almost certainly provoke an armed U.S response. To blunt that response, Japan decided to attack the U.S Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, hoping that the U.S would negotiate peace” (https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/why-did-japan-attack-pearl-harbor#:~:text=The%20Japanese%20decided%20then%20that,the%20Pacific%20and%20Southeast%20Asia.).

The US War Department (which is what it was called prior to 1947) was afraid that Americans of Japanese descent would act as spies or saboteurs on behalf of Japan, although there was no evidence to back up their fear. The Department of Justice disagreed and was concerned about violating the civil rights of Japanese Americans. But the Department of War won: “John J. McCloy, the assistant secretary of war, remarked that if it came to a choice between national security and the guarantee of civil liberties expressed in the Constitution, he considered the Constitution ‘just a scrap of paper.’Justyic In the immediate aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack, more than 1,200 Japanese community leaders were arrested, and the assets of all accounts in the U.S. branches of Japanese banks were frozen” (ibid.).

Roosevelt signed an executive order giving the military the right to restrict access to areas of the country from any citizens or noncitizens. While the word Japanese does not appear in the order, it became clear quickly that the order was designed to remove Japanese Americans from the West Coast. A War Relocation Authority was established to removed people of Japanese descent from the general society. Well over 100,000 were forced into camps. They were forced to sell their property, often at steep discounts.

One American citizen of Japanese descent, Fred Korematsu, was arrested for not leaving the exclusion area when required by the War Department. He took his case all the way to the Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled against him. The court’s ruling read, “Compulsory exclusion of large groups of citizens from their homes, except under circumstances of direst emergency and peril, is inconsistent with our basic governmental institutions. But when, under conditions of modern warfare, our shores are threatened by hostile forces, the power to protect must be commensurate with the threatened danger” (https://www.britannica.com/event/Korematsu-v-United-States). Justice Robert H. Jackson dissented: “Korematsu was born on our soil, of parents born in Japan. The Constitution makes him a citizen of the United States by nativity, and a citizen of California by residence. No claim is made that he is not loyal to this country. There is no suggestion that, apart from the matter involved here, he is not law-abiding and well disposed. Korematsu, however, has been convicted of an act not commonly a crime. It consists merely of being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived” (ibid.).

Eventually, those Americans were restored to their rightful citizenship. But it was a concatenation of events that led to what has to be one of the darkest moments in the history of the United States, at least in the 20th century.

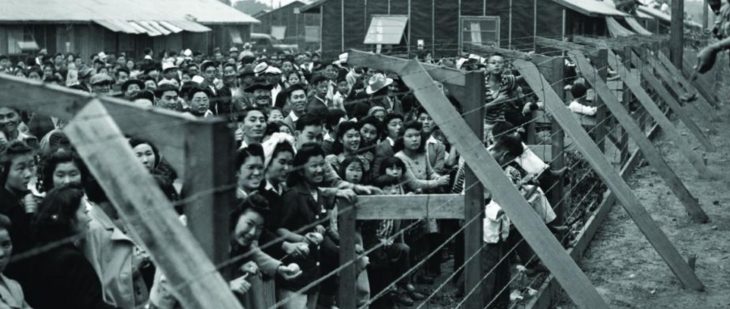

The image today: “Japanese Americans are imprisoned at Santa Anita, California, internment camp, 1942. (© Corbis)” (https://eji.org/news/history-racial-injustice-forced-internment-of-japanese-americans/).