Word of the Day: Amiable

Today’s word of the day, thanks to The New York Times, is amiable. Amiable is an adjective that means “having or showing pleasant, good-natured personal qualities; affable” or “friendly; congenial” or “agreeable; willing to accept the wishes, decisions, or suggestions of another or others” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/amiable). Merriam-Webster adds “pleasing; admirable” as archaic meanings: “When amiable was adopted into English in the 14th century, it meant ‘pleasing’ or ‘admirable,’ but that sense is now obsolete. The current, familiar senses of ‘generally agreeable’ (‘an amiable movie’) and ‘friendly and sociable’ came centuries later” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/amiable).

Amiable entered the English language in the “late 14c., ‘kindly, friendly,’ also ‘worthy of love or admiration,’ from Old French amiable ‘pleasant, kind; worthy to be loved’ (12c.), from Late Latin amicabilis ‘friendly,’ from Latin amicus ‘friend, loved one,’ noun use of an adjective, ‘friendly, loving,’ from amare ‘to love’ (see Amy).

“The form and sense were confused in Old French with amable ‘lovable’ (from Latin amare ‘to love’), and by 16c. the English word also had a secondary sense of ‘exciting love or delight,’ especially by having an agreeable temper and a kind heart. The word was subsequently reborrowed by English in Latin form without the sense contamination as amicable” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=amiable). That is, the Latin word amicus was reborrowed as amicable.

There have been a number of words that English has borrowed more than once. For instance, the word debt was first borrowed around 1300 (as dette) from the Latin debitum (“a thing owed”) through the French dete, and then debit was borrowed in the 15th century either from the French debet or perhaps directly from the Latin debitum. The b was added to dette by Latin scholars in the 14th century to reflect the Latin origin, but no English speaker has ever tried to actually pronounce it in the word debt.

On this date in 1843, the young United States of America lost one of the most influential men in American history, Noah Webster (1758-1843).

Noah Webster was born in Hartford, in what is today the state of Connecticut, before the Revolutionary War. He learned to read and write from first his mother and then teachers in a one-room schoolhouse, which he hated (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noah_Webster). But he must have been bright because his pastor taught him Latin and Greek to prepare him to go on to Yale College.

He attended Yale while also serving in the Connecticut militia, graduating in 1779. But after graduating, he had no definite plans. “Webster had a hard time finding a real job both after his liberal arts education at Yale (said he: ‘liberal arts education disqualifies a man for business’) or later as a lawyer” (http://lovelandbeacon.com/a-different-kind-of-storybook/). So he did a bit of teaching, even opening his own school. He also did some writing and editing.

In order to support that teaching, he started to write his own textbook, A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. “The work consisted of a speller (published in 1783), a grammar (published in 1784), and a reader (published in 1785). His goal was to provide a uniquely American approach to training children. His most important improvement, he claimed, was to rescue ‘our native tongue’ from ‘the clamour of pedantry’ that surrounded English grammar and pronunciation” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noah_Webster). The work came to be known as the Blue-Backed Speller. It became the most widely purchased book in the United States through the nineteenth century, and it influenced a wide variety of American writers.

In 1806, Noah Webster published his first dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. The very next year he began work on a more comprehensive dictionary that eventually was called An American Dictionary of the English Language. In order to accomplish this enormous task, “Webster learned twenty-eight languages, including Old English, Gothic, German, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, Dutch, Welsh, Russian, Hebrew, Aramaic, Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit” (ibid.). He published his second dictionary in 1828, but it did not sell particularly well. He borrowed money against his home so that he might work on a second edition, which was published in 1840. Still working on definitions, he died in 1843, saying “’I am entirely submissive to the will of God’” (ibid.).

“In A Companion to the American Revolution (2008), John Algeo notes: ‘It is often assumed that characteristically American spellings were invented by Noah Webster. He was very influential in popularizing certain spellings in America, but he did not originate them. Rather … he chose already existing options such as center, color and check on such grounds as simplicity, analogy or etymology.’ He also added American words, like ‘skunk’, that did not appear in British dictionaries” (ibid.). As a side note, I had Dr. Algeo for Old English when I first started my MA program at The University of Georgia. He was not only a professor but also the editor of American Speech, a top-tier journal. He was also a real gentleman.

After Webster’s death, the rights to his dictionary were purchased by brothers named Merriam, and they have continued to use the combined name to this day.

Noah Webster once said, “Language is not an abstract construction of the learned, or of dictionary makers, but is something arising out of the work, needs, ties, joys, affections, tastes, of long generations of humanity, and has its bases broad and low, close to the ground” (https://quotefancy.com/noah-webster-quotes). From this we can see that Noah Webster was not only the Father of American Education but also a linguist in the modern sense, recognizing that language is something functional, not a museum piece. But I have no idea how amiable he might have been.

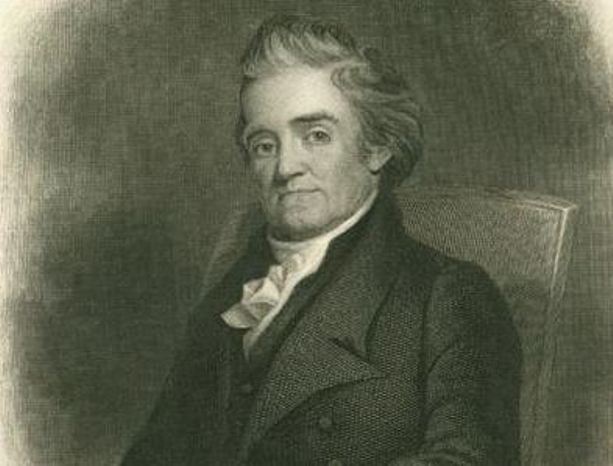

Today’s image is a “Detail of Noah Webster from a mid 19th century engraving – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online” (https://connecticuthistory.org/people/noah-webster/).