Antiques in the Nursery

Dynestee Fields

The literary palates of children have been a great debate in the adult world. The participants in this war of philosophies include authors who dream of catering to youthful desires, educational figures who seek to embody the great hand of Fate, and adults who wish to dissociate themselves from “childish” fantasies. In his essays, “On Three Ways of Writing for Children” and “On Juvenile Tastes,” author C.S. Lewis describes the folly of treating children as though they are a special subspecies of the human race. He also discusses the practice of treating children with great care as to not injure them mentally by providing them with fantastical stories. In regard to his own party, Lewis confesses to belonging to a class of writer who crafts children’s stories because they are the best art-form for expressing the material at hand (Lewis 35).

In order to arrive at the level of thinking at which the treatment of children and their literary interests become an issue, the adults that are not of the same class as Lewis’s writer must cast themselves into different roles than the ones that they inhabited as children. They move stories which they had cherished during childhood into the metaphorical nursery to act as hand me downs to children, and then begin to cast themselves into the roles of adults. Instead of allowing their interests to grow with them, they seek to replace them altogether. Like a house that has its foundation ripped away, the new adult interests attempt to root themselves firmly where the old interests once lay. However, not all of the minute stones can be removed. Although hidden, they still release echoes of old loves into the adult’s being.

Lewis rebukes this behavior as being contradictory to the adults’ original purpose. In order to forgo the ways of childhood and to be stamped with the seal of adulthood, they have resorted to the timid behavior of children who want to fit in with their elders. In essence, they have locked themselves within the constraints of arrested development. It is far better to age naturally and to let ones interests progress as they may, admonishes Lewis, than to go this route.

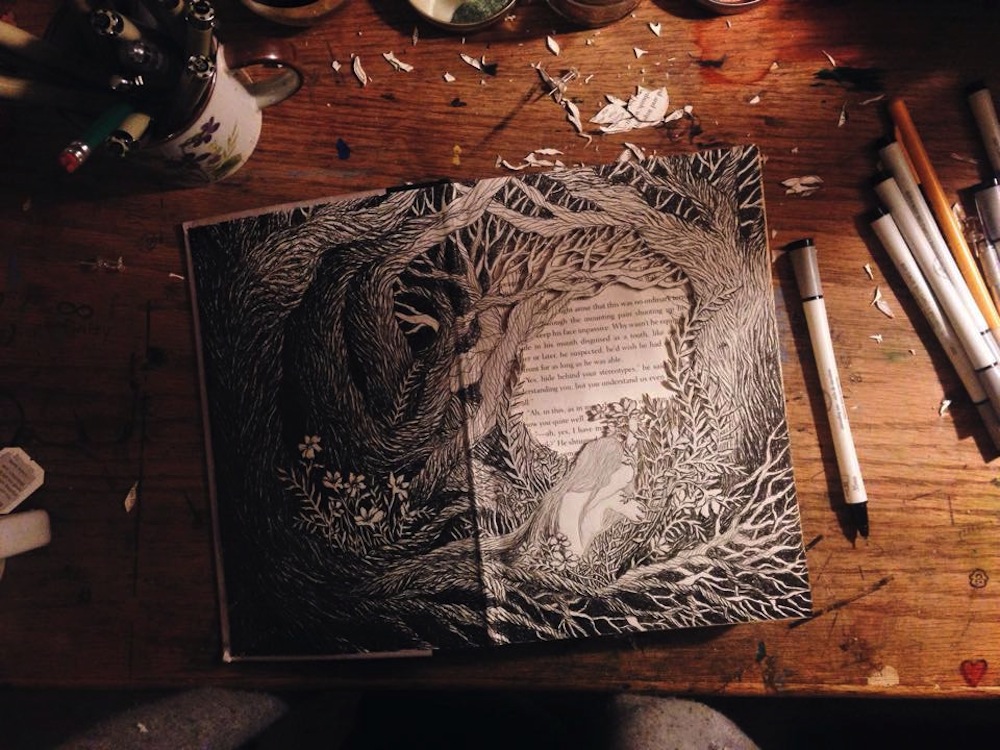

In fact, there is nothing to be feared from association with what is commonly deemed as children’s literature. The genres of fantasy and fairy tales, in particular, commonly get this treatment. While they once were much beloved elements of the adult world, they have been banished to the nursery for the children now that there is supposedly not much adult interest in them. There, according to Lewis, they sit in a degenerative state, slowly losing the glory of their original forms. This is a waste, because not all children love fantasy stories and not all adults dislike fairy tales.

In “Beyond Juvenile Tastes,” Lewis brings into focus the knowledge that many of the adults participating in this debate appear to have lost. “Of course their limited vocabulary and general ignorance make some stories unintelligible to them. But apart from that, juvenile taste is simply human taste” (Lewis 65). The lack of their understanding of this concept reflects directly in how they try to create material for this age group. Instead of concerning themselves with the production of stories that are true to themselves, many of them try to construct stories that are targeted at the supposed interests of different divisions of children. This writing has nothing to do with the author’s own interest, but only with what they believe will fulfil the desires of their target audience.

The other class of author is composed of writers who remain true to their personal interests. Like Lewis, they write about what interests them, which also happens to interest children as well. Society’s concern with literature has progressed to the point where specific age groups and interests are targeted and where the “appropriate” labels are applied to distinguish between subgroups. Unfortunately, while these authors acknowledge that both children and adults find joy in the fantastical and in fairy tales, they still must publish their stories under the Juvenile category in order for them to be taken seriously in the world of publishers. As a result, children have become the figure heads of these particular genres.

According to Lewis in “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” fairy tales and fantasy stories open up the mind to a spiritual exercise through which a little magic from the fantastical realm gets fused into the real world. The act of desiring works as a medium for connecting the reader to the revitalized world. This longing leads the reader to forget about their own reality momentarily, while they meet and face courageous knights and fiery villains in the realm of the story. These imaginary confrontations aid readers, especially children, in properly facing the trials that they encounter in reality.

Gerald K. Chesterton’s reasoning in his essay “The Romance of Childhood” simultaneously agrees and clashes with Lewis’s reasoning in these two essays. While Lewis’s primary concern is using the imagination as a means of broadening ones horizons and exploring beyond the original image, Chesterton relishes the idea that the limitations of imagination are what the soul truly desires. “The ordinary poetic description of the first dreams of life is a description of mere longing for larger and larger horizons,” (Chesterton 251) he says summarizing the approach that Lewis and many others have taken to analyzing the imagination (specifically that of children). However, “it is plain on the face of the facts that the child is positively in love with limits. He uses his imagination to invent limits” (Chesterton 251). In his view, the vast spaces of life and the imagination make the pieces that people choose to limit themselves to all the more important. Being able to create subdivisions and limitations turns attention away from the outward world and on to the inward.

Chesterton appears to have no desire for what he deems “the favorite nursery romances,” which he states that people may or may not be able to bring themselves to read again. However, he does appear to agree with Lewis heavily on the topic of not outgrowing interests. His belief from his youth was that liberty is something that manifests in the internal world as opposed to the external world. This belief persists throughout his adult life.

The world has changed dramatically since the days of Lewis and Chesterton. Adults are now rummaging through the antiques that they had formerly stored away in the nursery. However, something very drastic is happening. These stories that have degenerated into literary mush are now being transformed stylistically into tales that are appealing to older adolescents and adults. With Disney releasing a multitude of live action versions of its original fairy tales and with other sources redrafting traditionally victimized characters into warriors, it would seem that the adult world has readopted fairy tales and fantastical stories back into its repertoire.

However, are these stories a resurgence of the original tales, or are they merely sensationalist stories? It would appear that the latter is far closer to the truth. The direct correlation of these stories with the film industry appeal more to “technical novelties and with ‘ideas’, by which it means not literary, but social or psychological, ideas” (Lewis 65).

Just as the popularity of the young adult, dystopian novel has collapsed on itself and went into hibernation in recent years with the final cinematic installment of The Hunger Games, fairy tales will likely collapse once they have been over taxed. When this occurs, it is likely that fairy tales, which never emerged in their classic literary forms, will once again become antiques in the nursery.

(1). Chesterton, G.K. “The Romance of Childhood.” Chesterton, G.K. In Defense of Sanity. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011. 250-3. Print.

(2). Lewis, C.S. “On Juvenile Tastes.” Lewis, C.S. Of Other Worlds. Broadway, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1966. 61-5. Print.

(3). Lewis, C.S. “On Three Ways of Writing for Children.” Lewis, C.S. Of Other Worlds. Broadway, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1966. 33-53. Print.