Word of the Day: Perspicacious

Paul Schleifer

The first definition one finds in the OED for perspicacious is “keen, sharp; clear-sighted,” and then, “Chiefly fig.,” meaning that is used figuratively, not literally. The first sentence is cites is from 1616: “And canst thou with a perspicacious sight / Discern the show of truth from truth?” (I’ve modernized it a little). The second definition is “penetrating, perceptive, discerning,” used primarily about a person’s wit or intelligence. One sentence given is from Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo: “Women are idealists; but then they are so perspicacious.” The OED lists a third definition, “clear, transparent,” but it calls this meaning obscure and rare; indeed, it provides only one example, and that sentence comes from the writing of Percy Bysshe Shelley, so perhaps we can discount it entirely.

www.etymonline.com says that the word came into English in the 1630s, though we have seen an example in the OED from 1616. It then says the following: “formed as an adjective to perspicacity, from Latin perspicax “sharp-sighted, having the power of seeing through; acute,” from perspicere “look through, look closely at” from per “through” (from PIE root *per- “forward,” hence “through”) + specere “look at” (from PIE root *spek- “to observe”).”

The PIE root *spek– “is the hypothetical source of/evidence for its existence is provided by: Sanskrit spasati ‘sees;’ Avestan spasyeiti ‘spies;’ Greek skopein ‘behold, look, consider,’ skeptesthai ‘to look at,’ skopos ‘watcher, one who watches;’ Latin specere ‘to look at;’ Old High German spehhon ‘to spy, German spähen ‘to spy’” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/*spek-?ref=etymonline_crossreference). And the website lists a whole host of words derived from the PIE root, too long to put down here.

It’s interesting to me that we have this long Latinate word that ultimately comes from a very simple PIE root.

Today I’m remembering Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel (1738-1832), the German/British (he migrated to Great Britain at the age of 19) astronomer. Born in the Electorate of Hanover in the Holy Roman Empire, Herschel was not only an astronomer but also a musician. He played in the military band of the Hanoverian Guards, along with one brother and his father, but when the guards were defeated by the French at the Battle of Hastenbeck, his father sent him to England.

In England, he played for a variety of orchestras and churches. More importantly, through his music, Herschel met the Rev. John Mitchell, a clergyman who had been a professor of mathematics and who was also a scientist; Mitchell constructed telescopes, one of which Herschel bought from Mitchell’s estate. He also met Nevil Maskelyne, a clergyman and member of the Royal Society who became England’s fifth Astronomer Royal. Maskelyne was also part of the failed attempt to track the transit of Venus in 1761, an attempt ruined by bad weather.

In March of 1781, while looking for double stars in the galaxy (a project Herschel worked on for years), Herschel noticed a flat disk which he thought might be a comet or stellar disk. Upon consulting with the Russian Anders Lexell, Herschel agreed that this new find was actually a planet outside the orbit of Saturn. He initially called it the Georgian planet (named after King George III), but the French didn’t like the name. Eventually Uranus was settled on.

In February of 1789, Herschel wrote in his notes regarding the newly discovered planet, “A ring was suspected.”

Then, for almost 200 years, no astronomers mentioned rings at all.

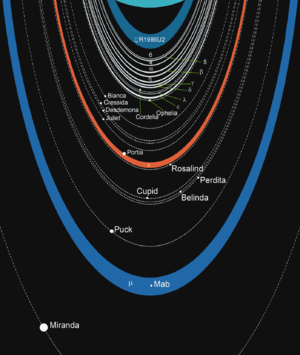

Then, on 10 March 1977, James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink, using the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, while trying to study Uranus’s atmosphere by the observation of the planet’s occultation of a star, discovered rings. At first it was thought that the planet had 5 rings, but further discoveries using the Voyager 2 and the Hubble Space Telescope have brought the number of rings up to 13.

So a guy with a home-made telescope discovered something almost 200 years before anyone else saw it, and those later astronomers had some really great technology to see what the first had seen all those years ago.

I’d say that Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel was literally perspicacious.

The image is “a scheme of the rings and close moons of Uranus. Rings are full lines, to scale if possible. Orbits of moons are dashed. No claim at accuracy, excentricity, or size of moons.” The author is called Trassiort, and Trassiorf has placed the image into the public domain.