Word of the Day: Denouement

Paul Schleifer

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, denouement means “Unravelling; spec. the final unravelling of the complications of a plot in a drama, novel, etc.; the catastrophe; transf. the final solution or issue of a complication, difficulty, or mystery.”

Perhaps the dictionary.com definitions would be easier to get: “1. the final resolution of the intricacies of a plot, as of a drama or novel. 2. the place in the plot at which this occurs. 3. the outcome or resolution of a doubtful series of occurrences” (http://www.dictionary.com/browse/denouement?s=t).

Or maybe not. I don’t want you to confuse it with the climax. The climax is “the highest or most intense point in the development or resolution of something” (http://www.dictionary.com/browse/climax?s=t).

Let me try to explain the difference with an example. The climax of Henry V comes when the English defeat the French at the Battle of Agincourt, at the end of act 4. Act 5 is taken up with Henry’s wooing Catherine and the negotiations between Henry and the French king. All of act 5 is, therefore, denouement. On the other hand, the climax of Macbeth comes in act 5 when Macduff kills Macbeth, Macduff being the man who was not of woman born. After Macbeth’s death, the play is over in a couple of minutes, with not much of a denouement at all.

One of the interesting things about denouement is that, even though it has been in the language for over 250 years, we still pronounce it as if it were a French word. Here is the etymology according to www.etymonline.com: “1752, from French dénouement ‘an untying’ (of plot), from dénouer ‘untie’ (Old French desnouer) from des– ‘un-, out’ + nouer ‘to tie, knot,’ from Latin nodus ‘a knot,’ from PIE root *ned– ‘to bind, tie.’” So after 250 years, one might think that the pronunciation of the word had been Anglicized, but no. The pronunciation is /ˌdeɪ nuˈmɑ̃/ (dey-noo-mahn). If it were Anglicized, it would have its emphasis on the second syllable, the middle syllable would sound more like now, and it would end with /mɘnt/ (“munt”).

March 12 was, prior to 1969 when the 2nd Vatican Council changed things, the feast day of Pope Gregory I, St. Gregory the Great, who died on this day in 604 CE. Gregory was the Pope from 3 September 590 (the date of the new feast day) until his death 13 and a half years later. During his 14 years he accomplished a great many things: he made the giving of alms a centerpiece of the Church; he made substantial reforms to the liturgy, some of which remain to this day; he is given credit for the form of plainsong that came to bear his name, Gregorian Chant; he wrote extensively, and many of his works are extant; and he is credited with having created the medieval papacy.

In addition, Gregory was responsible, at least in part, for sending St. Augustine of Canterbury to convert the Anglo-Saxons. Augustine started with the Kingdom of Kent. King Æthelberht had married a Christian wife, and as part of the terms of the marriage, she was allowed to bring her priest with her. Æthelberht proved friendly to Christianity, eventually converted (happy wife, happy life, right?) and allowed missionaries to proselytize among his people. He even gave the church land for the building of a monastery. Eventually, Æthelberht’s capital, Canterbury, became the primary seat of the Christian church in England. Augustine kept in touch with Gregory (as much as one could in the late 6th/early 7th centuries), and Gregory advised Augustine on a whole host of issues.

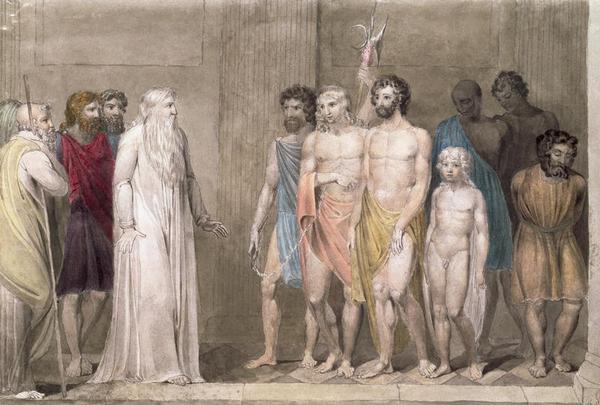

The story, as told by the Venerable Bede, is that some Anglo-Saxons were being sold at auction in Rome. With their fair hair and skin, they were quite pleasing to look at. Gregory was told that they were Angles (like Anglo-Saxons). Gregory’s response was, according to the Ecclesiastical History of England, “Sed Angli, non Angeli.” Thus Gregory wanted to convert these angels to the true faith. And some credit Bede with inventing the idea that the English were a kind of modern chosen race.

There is a long history of the English church after this dramatic moment when Gregory recognized the angelic nature of the English people and determined to convert them, but all of that is not the climax but rather the denouement.

The image is one by William Blake, entitled Sed Angli, non Angeli, “not angles but angels.”