Word of the Day: Dictator

Paul Schleifer

The OED defines dictator as “A ruler or governor whose word is law; an absolute ruler of a state.” That is extended, as a kind of metaphor, to “A person exercising absolute authority of any kind or in any sphere; one who authoritatively prescribes a course of action or dictates what is to be done.”

According to www.etymonline.com, the word came into English in the late 14th century from the Latin word dictator, an agent noun (a noun derived from a verb to show who does that action) from dictare. The second meaning of the word appeared around 1600.

Dictare (dicto, dictas, dictavi, dictatum) is a Latin word with several meanings, but we’ll stick with “to order; to prescribe). So a Roman who ordered or prescribed something was (agent noun) a dictator.

In the earliest days of Rome, the Romans had a king like every other tribal group in what is now Italy. But they got rid of the king in favor of the notion that the people themselves were sovereign, and they chose a Senate. They also chose two consuls to be in charge of the military, like generals.

But every once in a while, because of some imminent threat, they would appoint a leader for a period of six months who had absolute power. If this leader said it, you did it; hence, he was a dictator.

Here’s an example of how it worked. In 458 BCE, the Aequi, an Italian tribe, attacked Rome. The two consuls led armies to engage the Aequi¸ but one of them screwed up, and things were not looking good for the Romans. So the Senate appointed as dictator a man who had recently been forced to sell his properties in Rome to pay fines he incurred because of actions by one of his sons. This man had had to move outside of Rome to a farm, and when the representatives of the Senate came to tell him that he had been appointed dictator, he was plowing his field. The man’s name was Cincinnatus.

The thing that is truly remarkable about Cincinnatus is this: in his first appointment as dictator, he responded to the call of the people, assembled his army, led the army against the Aequi, forced them to surrender, and returned to Rome in just 3 weeks. He could have stayed on as dictator for the rest of the 6 months, but he immediately resigned his position. I wish today’s politicians would be more like Cincinnatus.

But another great Roman dictator is remember today. March 15 is the anniversary of the death of Julius Caesar, who should have listened to whoever said, “Beware the Ides of March.”

Caesar was born to an aristocratic family, but it wasn’t a rich family. He worked his way up the governmental ladder, so to speak. He put together a private army to defeat Mithradates VI of Pontus, who had declared war on Rome. When he was about 40, he was appointed governor of Spain, which was a Roman province. He became close to Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, or Pompey the Great. Then he convinced Pompey’s rival, Marcus Licinius Crassus, to join with Pompey and him in the first Triumvirate, an alliance to gain political power.

Caesar used Pompey’s fame and Crassus’s wealth to springboard his career. He became governor of Gaul and raised an army to conquer most of the rest of that land. But the alliance among the three was strained, and eventually Crassus died in battle in Syria. Then in 49 BCE, Pompey and Caesar went to war against each other. This is where Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his army.

By 48 BCE, Caesar had driven Pompey and his army out of Italy and across the Mediterranean to Egypt. Caesar followed, and eventually Pompey was killed in battle. Meanwhile, Caesar had developed a relationship with Cleopatra, and she became his mistress.

Caesar finally returned to Rome in 45 BCE. He was then made dictator for life, a very unusual move. During this term of office Caesar reformed the government in a whole host of ways, increasing the size of the Senate so that it more adequately represented all Romans, reviving the cities of Carthage and Corinth, which had been destroyed by his predecessors, and expanding Roman citizenship.

But he also scared a lot of Romans because, despite the fact that a dictator for life sounds an awful lot like a king, the Romans feared that Caesar wanted to become a king. Part of the fear was created by Caesar’s relationship to the queen, Cleopatra. She was not even allowed to enter the city of Rome and had to dwell outside.

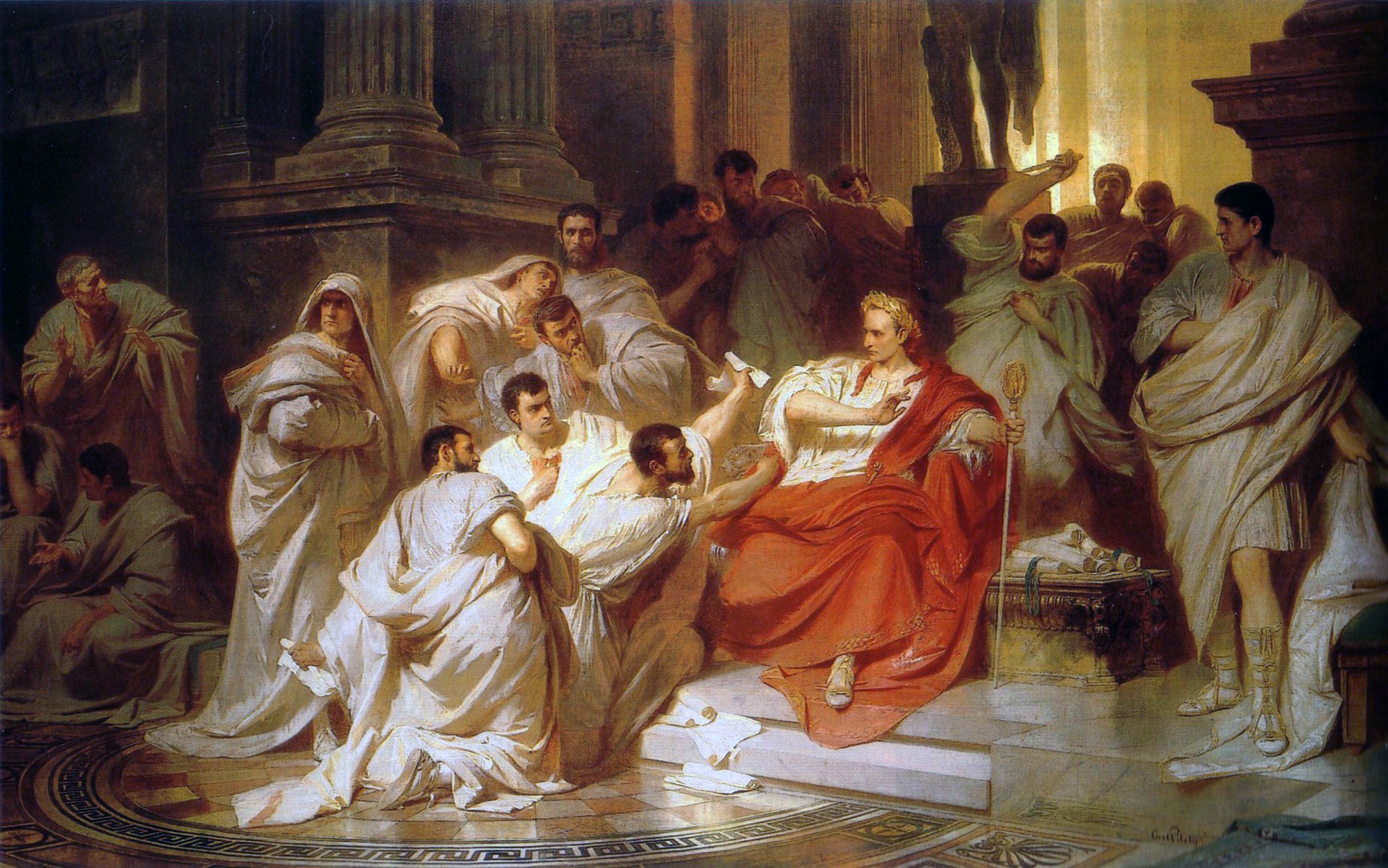

Finally, a conspiracy led to the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BCE, the ides of March, the end of the dictator for life. I wonder what Caesar would have said had he lived.

The image is Karl von Piloty’s The Murder of Caesar (1865). There is no evidence that Caesar actually said, “Et tu, Brute” before he died.