Word of the Day: Beneficent

Paul Schleifer

Beneficent means doing good or performing good deeds. Unlike beneficial, the emphasis is on the second (not the third) syllable: /bɪˈnɛfɪsənt/.

The word evolves in English in a somewhat unusual way. First the language came up with the word beneficence, which comes from the Latin benefactum. In Latin, bene– means “good,” and factum means “a deed” or “an act.” From factum we also have words in English like factotum (someone who does everything), factor (a person who does things for someone else, an agent), and factory (a place where something is done).

Beneficence is evident in the language as early as 1531, in The Boke of the Gouernour by Thomas Elyot: “Beneficence can by no menes be vicious, and retaine still his name.”

There are a host of words with the –ence (or –ance) ending, and here’s what www.etymonline says about that ending:

“word-forming element attached to verbs to form abstract nouns of process or fact (convergence from converge), or of state or quality (absence from absent); ultimately from Latin -antia and -entia, which depended on the vowel in the stem word, from PIE *-nt-, adjectival suffix.

“As Old French evolved from Latin, these were leveled to -ance, but later French borrowings from Latin (some of them subsequently passed to English) used the appropriate Latin form of the ending, as did words borrowed by English directly from Latin (diligence, absence).

“English thus inherited a confused mass of words from French and further confused it since c. 1500 by restoring -ence selectively in some forms of these words to conform with Latin. Thus dependant, but independence, etc.”

Then what happened is this: abstract nouns with the –ence ending can be turned into adjectives by changing the –ence to –ent. Think of words like magnificence or opulence. Like those words, beneficence becomes beneficent in the 1610s even though English already had a similar adjective, beneficial, that dates back to the 1400s. So the two words have to undergo a bit differentiation.

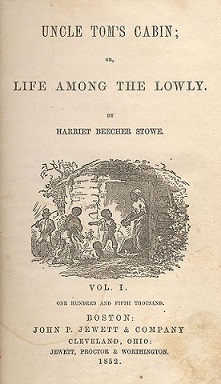

March 20, 1852, is the publication date of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It is not the first appearance of the novel in print. Stowe initially published her novel serially (a very popular way of publishing novels: Charles Dickens published most of his work serially) in The National Era, an abolitionist periodical. The publisher of the Era, John P. Jewett, saw how popular it was in serial form, so he convinced a doubtful Stowe to publish it in book form. In its first year, it sold 300,000 copies, an astounding success.

A lot people give Stowe credit for starting the Civil War, but that is probably not true. There is the (probably) apocryphal story about Lincoln’s meeting Stowe and saying, “So this is the little lady who started this great war.” Stowe herself made no mention of this statement, and the quote doesn’t appear in print until 1896, but who knows for sure? But the problem is the timing. After the initial success of the novel, demand for it dried up until it 1862. Jewett had gone out of business, and the rights to publication were picked up by another publisher, who brought the book out in 1862, when it began to sell quite well. The book was also translated into many other languages and sold well around the world, especially in England.

Stowe was inspired to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin by reading slave narratives, particularly The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (1849) and other works about slavery. In 1853, Stowe published A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was supposed to show all the sources she had consulted in creating her depiction of slavery in the American South, but scholars have determined she did not read some of those works until after she wrote the novel.

Daniel R. Vollaro, in “Lincoln, Stowe, and the ‘Little Woman/Great War’ Story: The Making, and Breaking, of a Great American Anecdote” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 30.1 (2009), says the following about the apocryphal Lincoln story:

“The long-term durability of Lincoln’s greeting as an anecdote in literary studies and Stowe scholarship can perhaps be explained in part by the desire among many contemporary intellectuals to make literature a lever of social or political change. The 1960s made the explicit politicization of literature popular among an entire generation of literary scholars and historians; in this milieu, Stowe’s novel seems like the ultimate example of a literary work exerting revolutionary influence on American society. Like Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle, Uncle Tom’s Cabin can be cited to affirm the role of literature as an agent of social change.” (https://web.archive.org/web/20091015043157/http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/30.1/vollaro.html)

As a literary scholar, I do believe in the efficacy of literature as an agent of social change. Ultimately, I think literature can be not only good but also beneficent.

The image is the title-page illustration by Hammatt Billings for Uncle Tom’s Cabin [First Edition: Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1852]. It shows the characters of Chloe, Mose, Pete, Baby, Tom.