Word of the Day: Abstruse

Paul Schleifer

According to www.etymonline.com, abstruse entered the language in the “1590s,” and that it means “’remote from comprehension,’ from Middle French abstrus (16c.) or directly from Latin abstrusus ‘hidden, concealed, secret,’ past participle of abstrudere ‘conceal, hide,’ literally ‘to thrust away,’ from assimilated form of ab ‘off, away from’ + trudere ‘to thrust, push,’ from PIE root *treud- ‘to press, push, squeeze.’”

So abstruse comes to mean “difficult to understand; obscure,” or “concealed, hidden, secret,” though the latter definition is labeled obsolete by the OED.

On this date 415 years ago James Charles Stuart, James VI, King of Scotland, became the King of England, having been designated the heir by the dying Queen Elizabeth I. He was the great, great grandson of Henry VII, Henry Tudor, who had begun the Tudor dynasty, and the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, whom Elizabeth had executed for treason in 1587. James had become King of Scotland in 1567, at the age of 13 months, when Mary was forced to abdicate by the lairds. He was 37 when he took the English throne.

James reigned for 22 years. It was a fairly quiet reign, at least after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Like his predecessor, James acted the part of a religious moderate, playing the Anglican middle against the Catholics on one side and the Puritans on the other. He was quite tolerant of Catholics who agreed to take the Oath of Allegiance and who kept quiet about their faith (although Catholics were denied certain civil rights, like voting and education, until the 19th century). He persecuted the more radical, outspoken Puritans. And his efforts of getting the kirk in Scotland to become Anglican, he was met with quiet resistance from the clergy.

But there were no wars of significance during James’s reign, a period that is referred to by scholars as the Jacobean period because James is the English version of the Latin Jacobus. He actively pursued a policy of peace, against the wishes of some hawkish Puritans who wanted war against Spain, and if there were nothing else good about James’s reign, this pursuit of peace must be commended.

The biggest issue among historians today regarding James’s reign is his sexuality. He had, apparently, close relationships with some of his courtiers, particularly George Villiers. According to H. Montgomery in The Love That Dared Not Speak its Name (London: Heinemann, 1970: 43–4), there was a popular saying at the time, “Rex fuit Elizabeth, nunc est regina Iacobus” (Elizabeth was king; now James is queen). But much of the contemporary criticism of James, describing his relationships with his male friends, is from radical Puritans, who may not be the most objective commentators. During his reign, James had seven children by his wife, and he was well known as a devoutly religious man. He even wrote and published three works before his ascension to the English throne: Daemonologie (1597), The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598), and Basilikon Doron (1599). The latter two works are on political theory, the origin of scholars focusing on James’s belief in the Divine Right of Kings, but the first is magic and necromancy, how demons interfere in the lives of men (it may have been his interest in witches that led to Shakespeare’s writing Macbeth).

In fact, James was so devout that he decided to sponsor a team of scholars to come up with a new translation of the Bible. There had been two earlier official translations, but people were unhappy with both of them for various reasons, religious and political. James brought in 47 scholars to work on the new translation, and when it was done, it became the authorized version. It remained the most important English translation of the Bible until the second half of the 20th century, and it is still considered by some (mostly old people) the only translation.

I grew up with King James Bible, and there are certain passages of Scripture that will forever be in my head in the King James version:

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures:

he leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul:

he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil: for thou art with me;

thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies:

thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life:

and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever. (Psalm 23)

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity. (1 Corinthians 13: 11-13)

I was on a tour in England some years ago, and the tour guide, who claimed a Master’s in history from Oxford or Cambridge (I cannot remember which), told us that toward the end of the translation period King James asked his 47 scholars to identify the finest poet in England, intending to ask this poet to give the translated Scripture a once over looking for consistency in style. The poet chosen, according to the tour guide, was William Shakespeare, and correspondence between James and Shakespeare resulted, with Shakespeare doing a final once over. This story, of course, is not at all true, but it sure makes a nice story.

But it is true that the King James version of the Bible is a beautiful version (though it took a lot from the Geneva Bible, which is also beautiful). And for someone who has a Ph.D. in English Renaissance literature, it is quite enjoyable to read. Sadly, very few people today have a Ph.D. in English Renaissance literature, making the KJV less than optimal as a way of reading Scripture.

Why, you ask? Because it is abstruse.

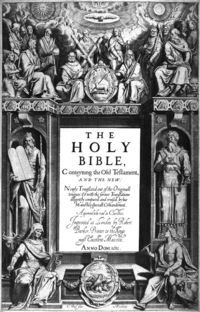

The image is the “Frontispiece to the King James’ Bible, 1611, shows the Twelve Apostles at the top. Moses and Aaron flank the central text. In the four corners sit Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, authors of the four gospels, with their symbolic animals. At the top, over the Holy Spirit in a form of a dove, is the Tetragrammaton “יהוה” (“YHWH”).” The “author” is the Church of England, and the source of the image is the University of Pennsylvania.