Ghosts, Big Business, and the Hope for Something More

Samantha Michalski

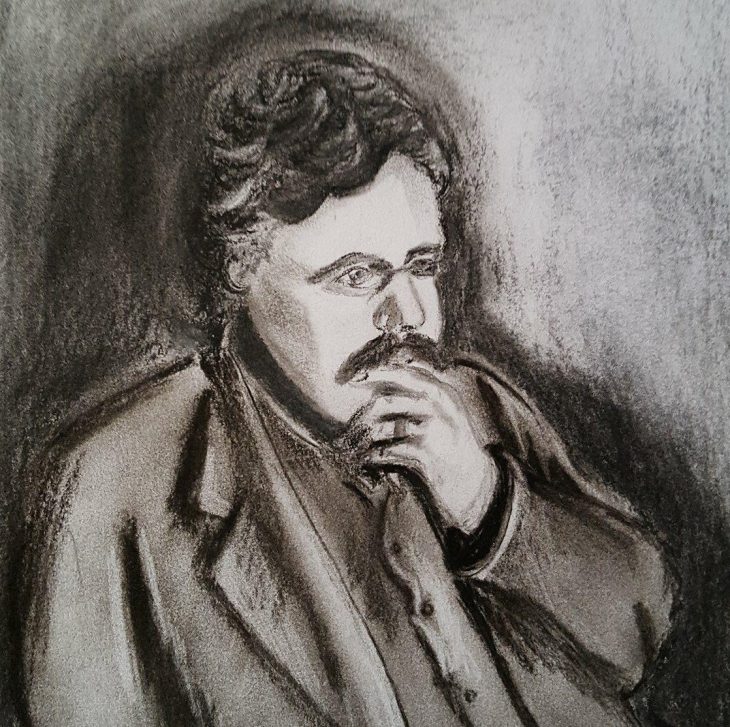

G.K. Chesterton was a mastermind when it came to writing and explaining things that seemingly had no connection. In his three essays, “The Bluff of Big Shops”, “The Shop of Ghosts”, and “The Architecture of Spears” he does this impeccably.

Chesterton had his own way of thinking and understanding. In his essay “The Architecture of Spears” he expresses this well. This essay is primarily about an optical illusion that Chesterton experienced when looking at a Gothic church in the small town of Lincoln. While looking at the church, Chesterton does not see a church, but a knight or soldier with a spear. He had mistaken the vans parked in front of the cathedral as cottages, when those began to move, he had begun to see the building move. He seemed to see the building striding across the land, “like the two legs of some giant whose body was covered with clouds.” This is when he fully realized what the building was. He goes on to explain that Gothic architecture is very much alive, “The truth about Gothic is, first, that it is alive, and second, that it is on the march. It is the Church Militant; it is the only fighting architecture.” In this section he really embodies the vision he is trying to get across. Explaining the spires as spears and the architecture as a Gothic knight protecting the Church, really helps to give us that vision. Chesterton does an amazing job of seeing things not as they are. He takes every day; ordinary objects and he turns them into some spectacular. Many people would never look at a cathedral in this way, as the Church Militant, but Chesterton does. He has the ability take seemingly boring or mundane objects and make them extraordinary.

In Chesterton’s essay, “The Bluff of Big Shops,” he explains big business as a shop, similar to those already in place in a small town, but much much larger. Chesterton had attempted to publish the essay, disparaging big business, in a newspaper, but the paper being a big business itself could not publish something of that manner. The newspaper could not risk downplaying its own kind with his work. Chesterton was trying to explain business taking over the small businesses. He uses the metaphor of small shops growing into one singular “big shop.” This seems absurd at first, but think about the world today, many companies have merged or taken over other, smaller companies or shops. There are not many shops that are singularly owned anymore, I personally own my own business. It is very difficult to run a business when there are many other corporations who make similar things and can sell them for much cheaper. That is part of the issue when it comes to big businesses taking over, they can make items at a much faster pace and they can sell those items for much cheaper. This is one of the things that Chesterton addresses in this essay. He even goes so far as to say, “That is to say, it is convenient to walk the length of the street, so long as you walk indoors or more frequently underground, instead of walking the same distance in the open air from one little shop to another.” This is obviously blasphemous, but as a society, even today, we buy into it. Over all, as a whole, we seem to find it more adequate to do this exact thing. Chesterton has yet again taken a concept that we all know, but he has turned it into something we have never noticed before.

The final Chesterton essay I will discuss is “The Shop of Ghosts.” This essay starts off seemingly about a simple toy shop, a magnificent toy shop full of many wonders and marvels. After walking into the shop and attempting to buy something, Chesterton addresses the man in charge. The man continues with this passage, “”No, no,” he said vaguely. “I never have. I never have. We are rather old-fashioned here.” “Not taking money,” I replied, “seems to me more like an uncommonly new fashion than an old one.” “I never have,” said the old man, blinking and blowing his nose; “I’ve always given presents. I’m too old to stop.” Not long after this encounter Chesterton realizes that the man is Father Christmas, or the spirit of him. Further on in the essay Chesterton tries to understand how Father Christmas could still be living, he wonders at this for a long moment. He continues later with, “”Good lord!” he cried out; “it can’t be you! It isn’t you! I came to ask where your grave was.” “I’m not dead yet, Mr. Dickens,” said the old gentleman, with a feeble smile; “but I’m dying,” he hastened to add reassuringly. “But, dash it all, you were dying in my time,” said Mr. Charles Dickens with animation; “and you don’t look a day older.” “I’ve felt like this for a long time,” said Father Christmas. Mr. Dickens turned his back and put his head out of the door into the darkness. “Dick,” he roared at the top of his voice; “he’s still alive.”” After this Chesterton tries explaining a very abstract idea to us, that even though Father Christmas, or the idea of him is old he is very much alive and thriving. He thrives in all situations because no matter what giving and helping and making people happy is what keeps the spark alive. Chesterton ends the essay with, “”I have felt like this a long time,” said Father Christmas, in his feeble way again. Mr. Charles Dickens suddenly leant across to him. “Since when?” he asked. “Since you were born?” “Yes,” said the old man, and sank shaking into a chair. “I have been always dying.” Mr. Dickens took off his hat with a flourish like a man calling a mob to rise. “I understand it now,” he cried, “you will never die.””

All things that Chesterton explains, in any and all of his essays, always turn into something else. He starts talking about something simple and he seemingly flips them into somethings else. He has a very good way of making people understand the vague in a very specific way.