Word of the Day: Bushwhacker

Paul Schleifer

A bushwhacker is a person who whacks his way through the bushes. Makes sense, right? The word is an Americanism. According to the OED, it first appears in a book by Washington Irving, A history of New York, from the beginning of the world to the end of the Dutch dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker, published in 1809: “They were gallant bush-whackers and hunters of racoons by moon-light” (II. vi. iv. 107).

Later, Union soldiers began referring to Confederate irregulars as bushwhackers because they fought a guerilla war while living in backwoods areas. Then, by a linguistic process called “back formation,” we got the verb “to bushwhack,” which means “To act as a bushwhacker; to beat the bush; to attack or kill in the manner of a bushwhacker” (OED). Of course, the meaning of the word in contemporary English, especially contemporary American English, has been generalized so that, for instance, a sports reporter might say that the Philadelphia Eagles bushwhacked the Cheatriots in the Super Bowl since the Cheatriots were supposed to win. It implies a kind of surprise attack.

According to www.etymonline.com, the word comes from the words bush and whack, kind of obviously. Bush, in the American colonies, came to mean “uncleared land,” and it developed a similar meaning in South Africa. Whack means “to strike sharply” and may be “imitative” (or “echoic” or “onomatopoeia”), a word that is supposed to sound like the sound it refers to. But the website also suggests that bushwhacker may be “modeled on Dutch bosch-wachter ‘forest keeper,’” though the Dutch wachter can also mean “guard” or “watcher.” This possible connection to the Dutch seems more likely given the first known use of the word by Irving in his faux history.

May 10 is the day that South Carolina, my adopted home state, “celebrates” Confederate Memorial Day. The state made the day an official state observance, including the closing of some state government offices, in 2000, the same year it officially recognized Martin Luther King, Jr., day. In “honor” of this day, then, here is the story of one of these Confederate “heroes” (though admittedly not one from South Carolina).

William Clarke Quantrill was born in 1837 in Ohio, the oldest of 12 children (though 4 died in infancy—a common occurrence before the discovery of antibiotics). His somewhat abusive father died of TB when he was a teenager, and the family fell into relative poverty. He tried to help his mother with the family finances by become a school teacher, at 16, but teaching did not pay well, so he tried other kinds of jobs, too.

Eventually, he went west with a couple of family friends, but this did not go well for William, who didn’t really like manual labor very much. The two men who tried to help him get established sued him when he failed to hold up his part of the bargain. Then he went to Utah with the army, but that didn’t work out well because he lost all he had gambling. Soon he became a drifter.

Although initially against slavery, by 1860 he wrote to his mother that he was in favor of the “peculiar institution” and that John Brown’s hanging was too good for the abolitionist. But his teaching career ended when the school he was working at closed. So he joined a band of brigands and engaged in cattle rustling, among other illegal activities. He also learned of a wonderful financial opportunity in hunting down run-away slaves and returning them to their masters.

In 1861, Quantrill traveled to Texas with a slave holder named Marcus Gill, a part-Cherokee who taught Quantrill guerilla warfare tactics. He and Gill joined the Confederate Army of Sterling Price and fought in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, but Quantrill left Price’s army to form an “army” of his own. This group, called Quantrill’s Raiders, fought on the Confederate side using guerilla tactics against the more traditional army of the Union side. Quantrill’s Raiders, eventually over 400 strong, were known particularly for their brutality. And they and other guerilla fighters like them were known as bushwhackers. Finally, the Union Army caught up with Quantrill at a farm in western Kentucky. Quantrill was shot in the back, while trying to flee, and was paralyzed. This event happened on May 10, 1865, a month after the Civil War was officially over. He died less than a month later.

But his legacy lived on through some of the men who “served” under him in Quantrill’s Raiders. They included “Bloody Bill” Anderson, Cole Younger, and Jesse and Frank James. That’s right—some of the most notorious outlaws of the Old West learned their craft from one of the heroes of the Confederacy.

I would never celebrate the death of any man, but it was perhaps, at least, appropriate that this ne’er-do-well and brigand was finally captured through a bushwhacking.

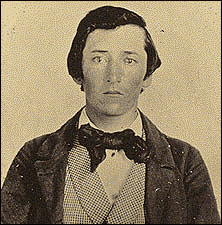

The image is a photo of William Clarke Quantrill. Humorously, he is referred to as “Capt.” The source is PBS.org, but the photo is anonymous and over 120 years old, so it is the public domain.