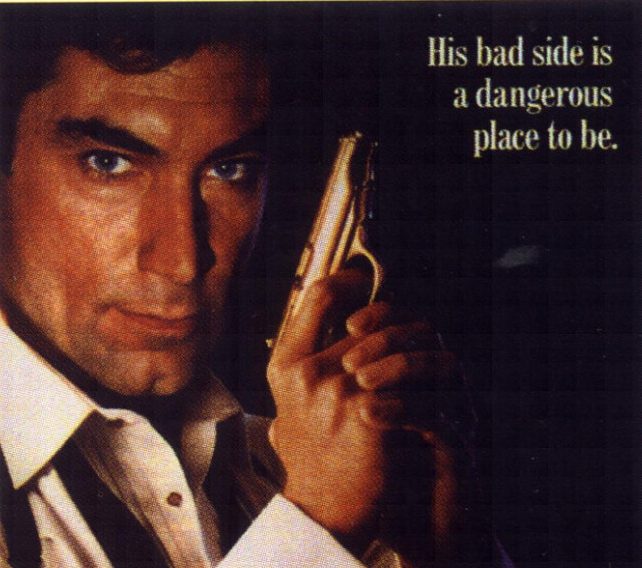

007 Dalton and License to Kill

Marshall Tankersley, Student Editor

What do you hate? Everyone, including Christians, hates something. Is it another person? An event? An action? Evil? Some individuals hate in wrong ways, in ways that end up only hurting others and themselves, while some individuals hate true evil with a righteous passion. License to Kill is a film about hatred and revenge, pitting the inimitable British agent James Bond against a villain who has made a personal attack against one of Bond’s most endearing friends.

Most of the time, Mr. Bond is the epitome of class, never fails to respond with a witty repartee to a megalomaniacal villain while dodging bullets with ease and never breaking a sweat. Most of the time, Mr. Bond works for the British government and what he does is in a solely official capacity. Most of the time, Mr. Bond operates with consummate professionalism, maintaining a very British distance between himself and the problems he deals with.

However, the circumstances and story of License to Kill are not normal and not average for our intrepid spy. This time, it’s not about official retribution against a villain, it’s a personal vendetta for James Bond himself. In his pursuit of justice as he sees fit, Mr. Bond serves as a vicarious representative for his audience and plays out the worldview of revenge.

The film opens with James Bond (Timothy Dalton) as the best man at his friend Felix Leiter’s wedding. Leiter (played David Hedison), an American agent, gets a tip that a very powerful drug lord named Sanchez has landed nearby, and he and Bond set out to capture him. In traditional Bond style, the villain is captured with great pomp and fanfare, and the two adventuring agents still manage to make it to the wedding on time. However, Sanchez (played by the talented and versatile Robert Davi) manages to escape and exacts a terrible revenge on the American agent who captured him. Sanchez has his men kill Felix’s new wife on their wedding night, and feeds half of Leiter himself to a shark.

When Bond discovers what’s happened and that the authorities have no way to extradite the now-free drug lord, he resigns his official role and sets out to find Sanchez and kill him. “Sir! They’re not going to do anything,” Bond says to his immediate superior, M, as M wants him to leave the matter in the hands of the legal system. “I owe it to Leiter. He’s put his life on the line for me many times.” Bond sees the pursuit of Sanchez as a matter of honor, as a favor returned to a man who has saved his own life before. In a restoration of this honor, Bond is determined that Sanchez must die.

Chasing the drug lord across multiple locations, Bond eventually manages to ingratiate himself into Sanchez’s inner circle, maintaining a sympathetic face for the villain while all the time plotting his demise. Bond comes into conflict with Drug Enforcement Agents who have also infiltrated Sanchez’s operation, but who are unfortunately killed by Sanchez. Eventually, Bond enters the lair of the lion, as it were, and is given a tour of Sanchez’s core drug operation. Here, he makes his move and instigates an action sequence that results in the destruction of the drug operation and the death of Sanchez.

After a crash of fuel trucks (which are just a cover for drug smuggling) on a dangerous and curvy mountain road, Bond is almost defenseless when he is approached by the furious Sanchez who is soaked in gasoline. While it seems as if our intrepid hero is finally without help, he asks Sanchez a compelling question: “Don’t you want to know why?” Sanchez is intrigued and lowers his weapon. Bond pulls out an engraved lighter that was a gift from Felix and his newlywed bride and uses it to set the gasoline-covered drug lord aflame. Bond has finally succeeded in his quest to bring down the maniac who mauled his friend, killed his friend’s wife, and hurt Bond.

License to Kill is, at its core, a classic revenge story. Bond doesn’t agonize over whether it would be an offense to God or man to kill Sanchez, and he certainly doesn’t dither about bringing the figurative knife down on the man’s back. He simply proceeds as a force of nature or avenging angel of death. The pursuit of justice and the elimination of a villain is the core theme of the film, almost as if Bond is Hamlet with no philosophizing about the morality of the actions. As an action movie with an action hero, neither the film nor Mr. Bond ever stop to ask whether revenge is morally right. They just presume that it is and proceed thusly.

The audience is invited to live vicariously through Bond (as in all of Bond movies) and revel in this unhinged justice. When one of Sanchez’s henchman gloats after killing Sharkey, one of Bond’s allies against Sanchez, Bond promptly fires a harpoon into his chest after uttering, “Compliments of Sharkey.” It feels as if some form of justice has been served. Perhaps not a justice the audience would feel comfortable admitting in everyday conversation, but a justice they feel keenly nonetheless and can explore vicariously through the character of James Bond.

The ultimate ‘thrill’ of the movie is not that our hero has destroyed Sanchez and his henchmen, but that the villains receive their just dues and ends, even if we feel uneasy about the methods and legality of Bond’s course. Some of the audience’s tension is ameliorated by the fact that the drug henchmen mostly kill each other, but Bond still takes justice into his own hands. The audience remains so disgusted with these utterly depraved characters and what they have done, that it’s hard for them not to cheer or want to pump their fists in the air when Mr. Bond fights against Sanchez’s men and ends some of their own lives.

The villains of the piece are portrayed without any kind of redeeming qualities. While Sanchez can sometimes be seen as the mirror image of Bond—smooth, charming, full of class—at heart the drug kingpin is a vindictive, violent, sadistic man, and his subordinates follow in his footsteps. These characters are designed to be hated by the audience, and they fill that role admirably. These characters are the kind of people the imprecatory Psalms in Scripture are written for; they’re utterly, heinously wicked, and (consciously or not) the audience wants to see them meet Divine retribution.

Throughout the film, our human nature cries out for justice where it has been denied, a cry that is answered cinematically with the incredible explosion that consumes Sanchez—a staged immolation that in fact was much larger than the director and the film’s stunt creators had intended, and might have placed those involved with the scene in danger. The ultimate ‘thrill’ of the movie is not that our hero has ended Sanchez and his henchmen, but that the villains have been repaid and justice has been settled. In that case, one can cheer for their just ends even if the question of whether or not Bond himself is justified in going outside of the law to do so is never asked or answered.

In License to Kill, the character of Bond is crafted differently than in most other Bond films for the betterment of the movie. Bond in other films is largely immovable, maintaining a kind of Olympian detachment from his circumstances. He’s capable of dealing with dangers, but he largely doesn’t appear to be affected by the aforesaid dangers. He’s mostly devoid of emotion, other than a rapier-sharp wit and whatever he requires to ‘get the girl’ as it were.

The Bond in License to Kill, however, is a much more empathetic character. Timothy Dalton as Bond plays him excellently, as the audience is convinced both that he cares about the wrongs done to Mr. and Mrs. Leiter as well as showing off his fury at Sanchez and his determination to bring him to justice. Dalton’s Bond is intense, dangerous, and most importantly, empathetic. The audience can relate to him now as a character, which is exactly what they need to do to care about the vendetta at the heart of the film.

Ultimately, the movie is a good one. One should not expect to receive a philosophy lesson from the film (it is a James Bond film, after all) but one can still learn from the film’s acting out a pre-determined philosophy. If want a civilized society where the wicked are punished and not allowed to prosper, then justice is a thing to be fought for and sought after. The deep-seated need to see retributive justice is present in all of humanity, and can be seen best not just in ‘real life’ where people can cover up their deepest and darkest feelings, but also in how they react to stories such as this one.

In the end, the question is put to all of us: would we act like James Bond if we were put in a similar position?