Word of the Day: Gallimaufry

Today’s word of the day is gallimaufry, a noun meaning “a hodgepodge; jumble; confused medley,” or “a ragout or hash,” according to www.dictionary.com. According to www.etymonline.com, the word first appeared in English in the “ 1550s, from French galimafrée ‘hash, ragout, dish made of odds and ends,’ from Old French galimafree, calimafree ‘sauce made of mustard, ginger, and vinegar; a stew of carp’ (14c.), which is of unknown origin. Perhaps from Old French galer ‘to make merry, live well’ (see gallant) + Old North French mafrer ‘to eat much,’ from Middle Dutch maffelen [Klein]. Weekley sees in the second element the proper name Maufré. Hence, figuratively, ‘any inconsistent or absurd medley.’”

I found the word in The Dictionary of Hard Words by Robert Morris Pierce, published in 1910 by Dodd, Mead, and Co. Dictionaries like this one have been around for over 400 years.

According to an article on the OED website, the first dictionaries were actually bilingual, intended to help people in English communicate around the continent: for instance, “The dictionary of syr Thomas Eliot knyght (1538), a Latin-English dictionary which went into several editions throughout the sixteenth century, Claudius Hollyband’s Dictionarie French and English (1593), and John Florio‘s Italian-English Worlde of Wordes (1598)” (https://public.oed.com/blog/the-first-dictionaries-of-english/). The Latin dictionary would have been important for anyone interested in education, because all scholarly writing was done in Latin. The French would have been important for members of the aristocrarcy; from 1066 onwards, most of the English aristocracy were originally Norman French, and French was the language of the upper classes for at least a few hundred years, but by the 1500s many of the English aristocracy spoke French poorly if at all. Furthermore, French was the lingua franca of the European continent, especially in tsarist Russia. A lingua franca is “any language that is widely used as a means of communication among speakers of other languages” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/lingua-franca?s=t), but the phrase itself comes from Italian and means “Frankish tongue,” or French.

The earliest English language dictionary, Robert Cawdrey’s “A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard usuall English words, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_Alphabeticall) or Table Alphabeticall for short, was, as its title suggests, a dictionary of the more difficult words in the English language. I guess even in 1604 teachers like Cawdrey perceived that the language was declining because young people weren’t spending enough time studying. Other hard word dictionaries followed: “John Bullokar‘s English Expositor (1616), Henry Cockeram’s English Dictionary (1623), and Thomas Blount’s Glossographia (1656)” (https://public.oed.com/blog/the-first-dictionaries-of-english/).

Interestingly, one of the concerns of these makers of dictionaries was the fear that too many words were being borrowed from other languages or from the lower classes. Throughout the 17th century, other writers presented the public with dictionaries of slang, or what was called “canting” dictionaries. Cant was the specific language of thieves and rogues; according to www.etymonline.com, it first meant “’pretentious or insincere talk, ostentatious conventionality in speech,’ 1709. The earliest use is as a slang word for ‘the whining speech of beggars asking for alms’ (1640s), from the verb in this sense (1560s), from Old North French canter (Old French chanter) ‘to sing, chant,’ from Latin cantare, frequentative of canere ‘to sing’ (from PIE root *kan- ‘to sing’).”

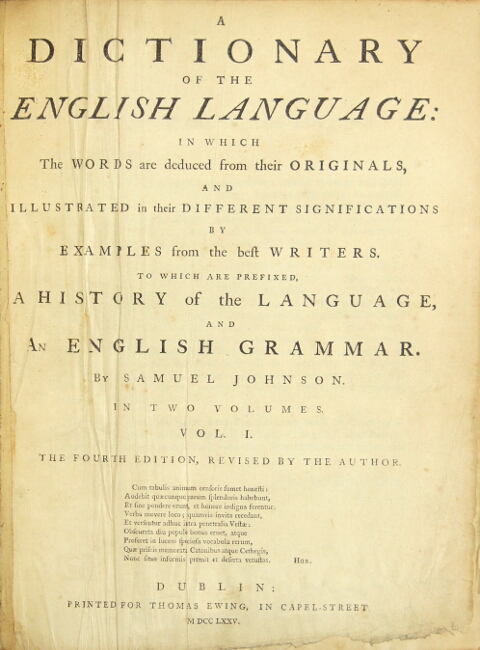

In 1746, a group of booksellers got together with the idea of creating a dictionary that was more than just hard words or slang, and they hired a man who really didn’t have a solid curriculum vitae. But young Samuel Johnson promised that he would be able to compile the dictionary they sought in three years. It didn’t happen as quickly as he had promised (it took seven), and he had to hire clerical support to help him put it together, but in 1755, he published A Dictionary of the English Language, the first relatively comprehensive dictionary based on historical principles in the language. It was the standard for English language dictionaries until the publication of the Oxford English Dictionary, which was begun in 1857 but not completed until…. In truth, it is still an ongoing project, though editions of the OED were published at times through the years.

Johnson’s Dictionary was a bit less objective than the OED, a bit more idiosyncratic. For instance, he defines oats as “’a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.” But perhaps the most famous definition in the Dictionary is that of the word lexicographer: “A writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.” But at least he tried to create a dictionary that wasn’t just a gallimaufry of hard words.

The image is of the title page of Johnson’s Dictionary as published in 1775 by Thomas Ewing in Dublin.