Word of the Day: Pragmatic

Today’s Word of the Day, thanks to WordThink.com, is pragmatic. Pragmatic is an adjective that means “More concerned with practical results than with theories and principles.” According to www.dictionary.com, it means “of or relating to a practical point of view or practical considerations” or “treating historical phenomena with special reference to their causes, antecedent conditions, and results.” It also has two more specialized meanings based upon philosophy.

According to www.etymonline.com, the word entered the English language in the “1610s, ‘meddlesome, impertinently busy,’ short for earlier pragmatical, or else from Middle French pragmatique (15c.), from Latin pragmaticus ‘skilled in business or law,’ from Greek pragmatikos ‘fit for business, active, business-like; systematic,’ from pragma (genitive pragmatos) ‘a deed, act; that which has been done; a thing, matter, affair,’ especially an important one; also a euphemism for something bad or disgraceful; in plural, ‘circumstances, affairs’ (public or private), often in a bad sense, ‘trouble,’ literally ‘a thing done,’ from stem of prassein/prattein ‘to do, act, perform’ (see practical). Meaning ‘matter-of-fact’ is from 1853. In some later senses from German pragmatisch.”

On this date in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus.

Habeas corpus is a Latin phrase meaning “literally ‘(you should) have the person,’ in phrase habeas corpus ad subjiciendum ‘produce or have the person to be subjected to (examination),’ opening words of writs in 14c. Anglo-French documents to require a person to be brought before a court or judge, especially to determine if that person is being legally detained. From habeas, second person singular present subjunctive of habere ‘to have, to hold’ (from PIE root *ghabh- ‘to give or receive’) + corpus ’person,’ literally ‘body’ (see corporeal) (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=habeas+corpus).

Americans have a Constitutional right to habeas corpus, which means that the person or people who arrest someone must prove to a court that they have the authority to arrest and detain that person. In other words, the police cannot just arrest you and throw you into the clink for days or weeks or months. They have to demonstrate that they have a legitimate case against you in front of a judge. And that judge gets to decide whether you stay in jail or not, prior to a trial.

Article 1 of the US Constitution addresses the power and limitations of the legislature of the US government. It is in Section 9 that we find the only mention of habeas corpus in the Constitution. It says, “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it” (https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articlei). This brief sentence is the only mention of habeas corpus in the Constitution. The power to suspend this essential right of the people is granted to the legislature only in the case of rebellion or invasion.

And in 1861, the US was facing rebellion. Most of the Southern states, including Virginia on April 17, 1861, had seceded from the Union, and Lincoln was fighting a war to force those Southern states back in. Maryland had not, in April of 1861, but Lincoln was concerned that it might. There were Southern sympathizers in Maryland, and Lincoln was concerned that the Maryland legislature was not loyal. The North’s supply lines to Washington, DC, ran through Maryland. So in order to prevent the Southern sympathizers from fomenting rebellion or causing violence against the Union. So on this date Lincoln ordered General Winfield Scott to suspend habeas corpus near any military lines between Philadelphia and Washington. He claimed that his authority came from Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution, but as we have already seen, that article authorizes the legislature to suspend habeas corpus, not the president.

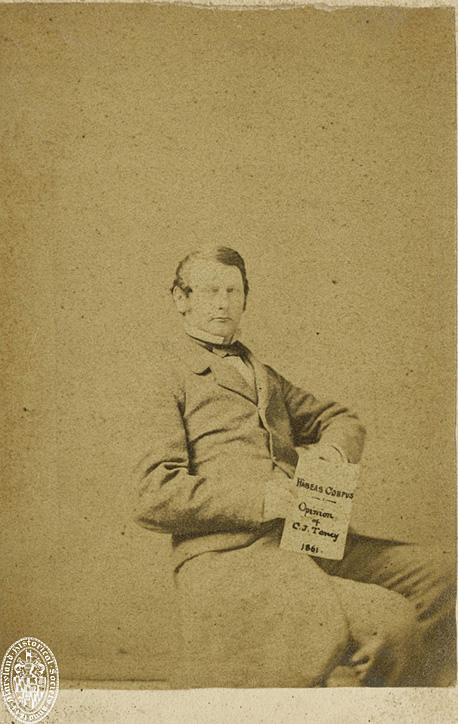

According to James A. Dueholm, “On May 25, federal troops arrested John Merryman in Cockeysville, Maryland, for recruiting, training, and leading a drill company for Confederate service. Merryman’s lawyer promptly petitioned Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, sitting as a trial judge, for a writ of habeas corpus (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0029.205/–lincoln-s-suspension-of-the-writ-of-habeas-corpus?rgn=main;view=fulltext). Taney eventually ruled against Lincoln. But Lincoln ignored the ruling. In July, he ordered the suspension of habeas corpus between New York and Philadelphia, despite Taney’s ruling. Lincoln’s order stayed in effect until 1863, when Congress passed legislation suspending habeas corpus for the public safety.

Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus from 1861 to 1863 was in clear violation of the Constitution, and he ignored the order of a judge in maintaining it. But he was being pragmatic. There have been a governors around the country in the last month or so issuing questionable orders for people to stay at home and for small business to close. The Michigan governor actually told wealthy citizens that they could not travel to their second homes within the state, though she claimed that she had no authority to prevent citizens of other states from traveling to their second homes within Michigan. But all these governors have justified their actions because of pragmatics, because things need to be done to slow the pandemic.

This is the conundrum—do we suspend people’s rights for good reasons, to be pragmatic? Or do we uphold people’s fundamental rights no matter what?

The picture is from 1861 and shows John Merryman, the Marylander whose detainment led to Judge Taney’s decision against Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, holding a copy of Taney’s decision.