Word of the Day: Wood

Today’s word of the day, thanks, partly, to the Old English Wordhord (https://oldenglishwordhord.com/2024/01/08/wodheortness/), is wood. But I’m not thinking of the wood that you are probably thinking of. This is an adjective that is described by Dictionary.com as “archaic,” meaning that contemporary speakers of English probably don’t use the word this way. This wood means “wild, as with rage or excitement; mad; insane” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/wood). The website provides some etymology: “First recorded before 900; Middle English wod(e), wodde, Old English wōd; cognate with Old Norse ōthr ‘mad, frantic’; akin to German Wut ‘rage,’ Old English wōth ‘song’ (because it was due to inspired madness.”

Etymonline echoes the above: “’violently insane’ (now obsolete), from Old English wod ‘mad, frenzied, from Proto-Germanic *woda- (source also of Gothic woþs ‘possessed, mad,’ Old High German wuot ‘mad, madness,’ German wut‘rage, fury’), from PIE *wet– ‘to blow; inspire, spiritually arouse;’ source of Latin vates ‘seer, poet,’ Old Irish faith ‘poet;’ ‘with a common element of mental excitement’ [Buck]. Compare Old English woþ ‘sound, melody, song,’ Old Norse oðr ‘poetry,’ and the god-name Odin.” The connection between madness and songs or poetry reminds one of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: The lunatic, the lover and the poet / Are of imagination all compact (5.1.7-8).

The word on the Old English Wordhord website is actually wodheortness, which means “madness” or “Insanity.” We actually have an example of this word, in the form wedenheortness, in the Venerable Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 2, chapter 5. Bede writes of King Eadbald, “he was troubled with frequent fits of madness” (http://www.heroofcamelot.com/docs/Bede-Ecclesiastical-History.pdf). We can find the word in Middle English in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde: “He sodeynly mot falle in-to wodnesse” (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/257/257-h/257-h.htm; Book 3, line 794).

On this day in 1916, the last of the British troops left the Gallipoli peninsula, ending one of the most disastrous escapades of World War I.

The Battle of Gallipoli, or the Battle of the Dardanelles, began in February of 1915. The Entente Powers (England, France, Russia) wanted to weaken the Ottoman Empire by occupying the Dardanelles Straights from which they could bombard the Turkish capital. When the attempt to force the Straights failed, the British decided to invade Turkey with what at the time was the largest amphibious invasion in history.

Unfortunately for the British, the invasion was a disaster, even though they stayed for eight months. By the time the Brits left, both sides of the battle had experienced somewhere near 250,000 casualties: “Officially, the dead included 2,700 New Zealanders, 8,700 Australians, 9,700 French, 21,000 British and 80,000 Turkish soldiers. So by the time this ten-month First World War campaign ended, about 120,000 men had died. And the wounded numbered around 260,000. The Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs put the figures higher, recording nearly half a million casualties” (https://www.onthisday.com/articles/gallipoli-guts-glory-and-defeat).

One political leader who lost his position because of the Battle of Gallipoli was Winston Churchill. Yes, that Winston Churchill. He was the First Lord of the Admiralty and had pushed the Gallipoli campaign. Many blamed the defeat on him. He, on the other hand, blamed a lack of support for the plan. The failure was also especially painful for the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), who felt that they were used as cannon fodder by the British command. Some historians assert that the failure of the Gallipoli campaign gave the Australians and the New Zealanders a sense of their own, separate identity.

Years later, in 1971, Eric Bogle (born in Scotland but immigrated to Australia) wrote a folk song about Gallipoli that became famous, called “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda.” The song has some historical inaccuracies and even an anachronism, but it reflects the attitude of many towards Gallipoli, and really to all wars. In fact, Bogle claimed that it was really more about Vietnam than about WWI. The song originally had eight verses, but Bogle later cut it down to five, and at the end it incorporates a couple of lines from the 1895 Australian folksong “Waltzing Matilda,” by Banjo Paterson.

Here are a link to the song on YouTube and the lyrics:

Now when I was a young man, I carried me pack

And I lived the free life of the rover

From the Murray’s green basin to the dusty outback

Well, I waltzed my Matilda all over

Then in 1915, my country said “son

It’s time you stopped rambling, there’s work to be done”

So they gave me a tin hat, and they gave me a gun

And they marched me away to the war

And the band played Waltzing Matilda

As the ship pulled away from the quay

And amidst all the cheers, the flag-waving and tears

We sailed off for Gallipoli

And how well I remember that terrible day

How our blood stained the sand and the water

And of how in that hell that they called Suvla Bay

We were butchered like lambs at the slaughter

Johnny Turk, he was waiting, he’d primed himself well

He showered us with bullets and he rained us with shell

And in five minutes flat, he’d blown us all to hell

Nearly blew us right back to Australia

But the band played Waltzing Matilda

When we stopped to bury our slain

We buried ours, and the Turks buried theirs

Then we started all over again

And those that were left, well we tried to survive

In that mad world of blood, death and fire

And for ten weary weeks, I kept myself alive

Though around me the corpses piled higher

Then a big Turkish shell knocked me arse over head

And when I woke up in me hospital bed

And saw what it had done, well I wished I was dead

Never knew there was worse things than dyin’

For I’ll go no more waltzing Matilda

All around the green bush far and free

To hump tent and pegs, a man needs both legs

No more waltzing Matilda for me

So they gathered the crippled, the wounded, the maimed

And they shipped us back home to Australia

The legless, the armless, the blind, the insane

Those proud wounded heroes of Suvla

And as our ship pulled into Circular Quay

I looked at the place where me legs used to be

And thanked Christ there was nobody waiting for me

To grieve, to mourn, and to pity

But the band played Waltzing Matilda

As they carried us down the gangway

But nobody cheered, they just stood and stared

Then they turned all their faces away

And so now every April, I sit on me porch

And I watch the parades pass before me

And I see my old comrades, how proudly they march

Reviving old dreams of past glories

And the old men march slowly, old bones stiff and sore

They’re tired old heroes from a forgotten war

And the young people ask, “what are they marching for?”

And I ask myself the same question

But the band plays Waltzing Matilda

And the old men still answer the call

But as year follows year, more old men disappear

Someday no one will march there at all

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?

And their ghosts may be heard

As they march by that billabong

Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?

(Source: LyricFind; Songwriters: Eric Bogle; The Band Played Waltzing Matilda lyrics © Music Sales Corporation, O/B/O DistroKid).

To me, the “leaders” who led the world into World War I and campaigns like Gallipoli, the Somme, and others, must all have been wood.

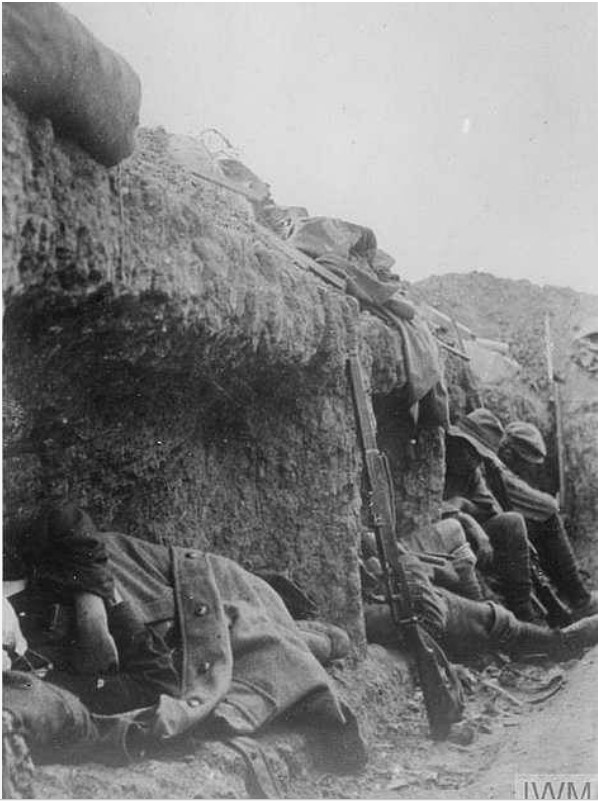

The image today is a photo of soldiers resting during the assault at Suvla Plain on August 21, 1915.