Word of the Day: Smart

Today’s word of the day is smart, and it may surprise you. Smart can be an adjective, a noun, or a verb. On the www.dictionary.com website, it has over 20 different definitions, though some are pretty to close to each other. As a verb, it basically means to cause a sharp pain or to feel a sharp pain. As an adjective, it can mean to be quick, or to be intelligent, or to be witty, or to be shrewd, or to be elegant (particularly in appearance), or to be brisk, or to be active, or to be severe, or to be sharp (as in a pain), or to be equipped with microprocessors, or to be easily adaptable to the environment, or even to be large. As a noun, it refers to a sharp physical pain, to mental anguish, or to the gift of intelligence. That’s a lot possibilities for one simple word.

The verb form of smart comes from the “Middle English smerten, ‘to cause pain, to suffer pain,’ from Old English smeortan ‘be painful,’ in reference to wounds, from Proto-Germanic *smarta– (source also of Middle Dutch smerten, Dutch smarten, Old High German smerzan, German schmerzen ‘to pain,’ originally “’to bite’). The Germanic word is perhaps cognate with Latin mordēre ‘to bite, bite into,’ figuratively ‘to pain, cause hurt,’ and both might be from an extended form of PIE root *mer- ‘to rub away, harm’” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/smart#etymonline_v_24152). Clearly the oldest meaning of the word has to do with causing or feeling pain.

The adjective form also goes back to the Old English: “Middle English smert, from late Old English smeart, in reference to hits, blows, etc., ‘stinging; causing a sharp pain,’ related to smeortan ‘be painful’ (see smart (v.)). The adjective is not represented in the cognate languages” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/smart#etymonline_v_24152). It’s interesting that the adjective form doesn’t exist in Dutch or German.

We can see the gradual broadening of the meaning in this entry: “Of speech or words, ‘harsh, injurious, unpleasant,’ c. 1300; thus ‘pert, impudent; on the impertinent side of witty’ (by 1630s). In reference to persons, ‘quick, active, intelligent, clever,’ 1620s, perhaps from the notion of ‘cutting’ wit, words, etc., or else ‘keen in bargaining.’” So the meaning changes from “painful,” as in a wound, to “painful,” as in words, to “impudent,” to “clever.” One thing we should keep in mind about the dates in these etymologies is that we can document when the words, with particular meanings, appeared in print. The words with those meanings likely appeared in the spoken language well before they appeared in print but we have no way of knowing precisely when.

As an adjective, etymonline also adds “From 1718 in cant as ‘fashionably elegant;’ by 1798 as ‘trim in attire,’” and “the sense of ‘behaving as though guided by intelligence’ is attested by 1972 (smart bomb, also the computing smart terminal).”

The noun form of the word also goes back at least to Middle English: “late 12c., smerte, ‘sharp physical pain,’ from smart (adj.). Cognate with Middle Dutch smerte, Dutch smart, Old High German smerzo, German Schmerz ‘pain.’ Of mental pain or suffering from c. 1300. In old cant, ‘a dandy,’ 1712. Smarts ‘good sense, intelligence,’ is recorded by 1968.” By the way, cant, while now it refers to hypocritical or sanctimonious speech, originally referred to the whining of beggars but broadened to referring to the peculiar speech or slang of people in the underworld, particularly in London. A variety of writers, including Robert Greene and Thomas Middleton, took some delight in revealing the thieves’ cant of Elizabethan England.

On this date in 1907, Dmitri Mendeleev died in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was born in 1834 in a village in Siberia. He did not come from a wealthy or upper-class background, though his father was a teacher and school principal and his mother from a family of merchants. After the death of his father, Mendeleev’s mother moved the family first to Moscow and then to St. Petersburg. Mendeleev was rejected by Moscow University but then accepted at a school in St. Petersburg.

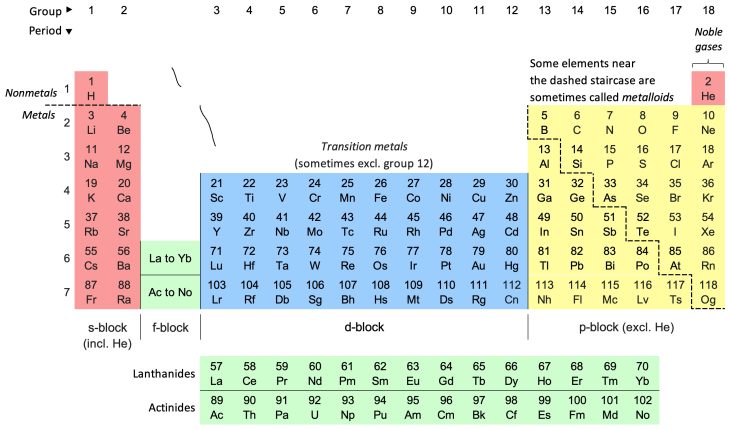

Mendeleev is best known as a chemist who created the Periodic Table. In the 1860s, he was teaching chemistry and even wrote what became the standard chemistry textbook. At that time, there were 56 recognized elements. Other chemists had been working on a way to categorize these elements, partly according to atomic weight and partly by other characteristics. But Mendeleev came up with the first table that not only categorized the known elements but also predicted elements that had yet to be discovered. For his work on the Periodic Table, Mendeleev almost won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1906—he fell one vote shy. Apparently, the work of one of the people on the committee had been critiqued by Mendeleev, and the grudge kept the Russian from receiving the prize.

Mendeleev did more than just create the Periodic Table. For instance, he studied the origin of petroleum, and he concluded that it has an abiotic origin. The traditional and widely accepted story of the origin of petroleum is that it comes from the decayed material of animals, large and miniscule, that through the process of decay turns into gas—hence the term fossil fuels. Mendeleev argued that oil is produced by natural but inorganic processes that take place far inside the earth. The discovery of methane on other planets seems to support his theory. And the argument has resurfaced in the media recently.

It’s telling when a scientist’s work leads to accurate predictions. It is a way of gauging the quality of such work. Dmitri Mendeleev must have been really smart to accomplish all he accomplished, though I think a lot of us found having to memorize the Periodic Table to be the other kind of smart.

The image today is Dmitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of the Elements, updated (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periodic_table).