Word of the Day: Fortitude

Today’s word of the day, thanks to Dictionary.com, is fortitude. According to the website, fortitude is a noun that means “mental and emotional strength in facing difficulty, adversity, danger, or temptation courageously” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/fortitude). It entered the language in the “late 14c., ‘moral strength (as a cardinal virtue); courage,’ from Latin fortitudo ‘strength, force, firmness, manliness,’ from fortis ‘strong, brave’ (see fort). From early 15c. as ‘physical strength’” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=fortitude).

My master’s degree is in Old and Middle English literature, and today’s word gives me the opportunity to revisit one of my favorite articles from those halcyon days, R. E. Kaske’s “Sapientia et Fortitudo as the Controlling Theme of Beowulf” (Studies in Philology 55.3 [1958]: 423-56). For me, it explains what is going on in Beowulf more than any other article or book I’ve ever read.

Here’s some background. Beowulf is an epic poem in Old English about a hero of the Geats. In the first section, young Beowulf, who has the strength of 30 men in his grip, travels from his home to Heorot, a famous mead hall that is being harassed by a monster named Grendel. Grendel, a descendant of the Biblical Cain, hates the Danes because they sing songs about God. Beowulf engages Grendel in hand-to-hand fighting and rips Grendel’s arm out of its socket. He follows Grendel to his mere, his home under the water, and finds a dead monster. He also finds Grendel’s mother and kills her after she attacks him. In the last section, it is 50 years later and Beowulf is now king of the Geats. A thief steals a cup from a dragon’s hoard, awaking the dragon. Beowulf goes to kill the dragon, which he does, but he also dies in the battle. Throughout the poem, the poet engages in digressions about other kings and queens from the past.

Kaske begins his article about Beowulf by giving credit to Ernst Curtius for developing the theme of sapiential et fortitude (wisdom and strength) in classical literature: “Ernst Curtius has sketched the development of the sapientia et fortitudo ideal in the Graeco-Latin-Christian tradition: its supposed origin in Homer and adaptation by Vergil, and its subsequent decline to a rhetorical [topos ‘convention’] expressing sometimes a combination of the two heroic virtues in a single hero, sometimes a separation of them anticipating the later tragedy of

Rodlanz est proz ed Oliviers est sages.”

The line is from the Chanson de Roland, an epic poem in Old French from the 11th century, and translates as “Roland is valiant and Oliver is wise.”

Kaske then explains that this theme, the description of the hero as both strong or brave or good in battle (or all three) and wise can be seen in a variety of Old English poems like Widsith and even some of the religious poetry. He explains what the two terms mean in the context:

“As the quality of a hero, fortitudo implies physical might and courage consistently enough. With regard to sapientia, we seem to have in Beowulf a general, eclectic concept including such diverse qualities as practical cleverness, skill in words and works, knowledge of the past, ability to predict accurately, prudence, understanding, and the ability to choose and direct one’s conduct rightly.”

Kaske looks at the main events as well as the digressions, which are frequently stories about heroic characters that lack either sapientia or fortitudo, from the perspective of this theme. For instance, Hrothgar, the king of the Danes and the one who built Heorot, is wise, but he’s old and no long has the strength to fight Grendel. Hygelac, the king of the Geats, is brave, but he dies in battle because he was not wise and took on the Swedes. Beowulf is both strong and wise until the end, when his strength fails him in the battle with the dragon.

Kaske concludes, “above the imperfection, the mutability, and in any case the final impermanence of human sapientia et fortitudo– and heightening its poignancy-there towers the Sapientia et Fortitudo of God, perfect, unchanging, everlasting. In that contrast lies, at its deepest and most inclusive, the tragedy of Beowulf.”

As I said, this analysis of Beowulf is the most enlightening one I have ever read. It gives real insight into the main story and the many other stories that occupy the poem. But beyond that, the theme of sapientia et fortitudo can help us to analyze the behavior of characters in other works of literature. For instance, Boromir, in The Lord of the Rings, is obviously a valiant warrior, but he is not wise. Bilbo, in The Hobbit, is very clever, a form of sapientia, but while he is at times brave, one would not think of him as valiant.

We could apply this to movies as well. In the original Star Wars movie, Obin Wan is wise, but he, like Hrothgar, is old and seems to have lost some of his fortitude. Han Solo is certainly valiant, but he does not come across as wise. Luke Skywalker, however, looks as if he is on the road to becoming both strong and wise.

Could we also apply this theme to real life? Could we look at our politicians and other leaders in terms of bravery and wisdom? If we were, I’m afraid that far too many of our political leaders, and probably even some of our military leaders, would prove to be lack in both sapientia and fortitudo.

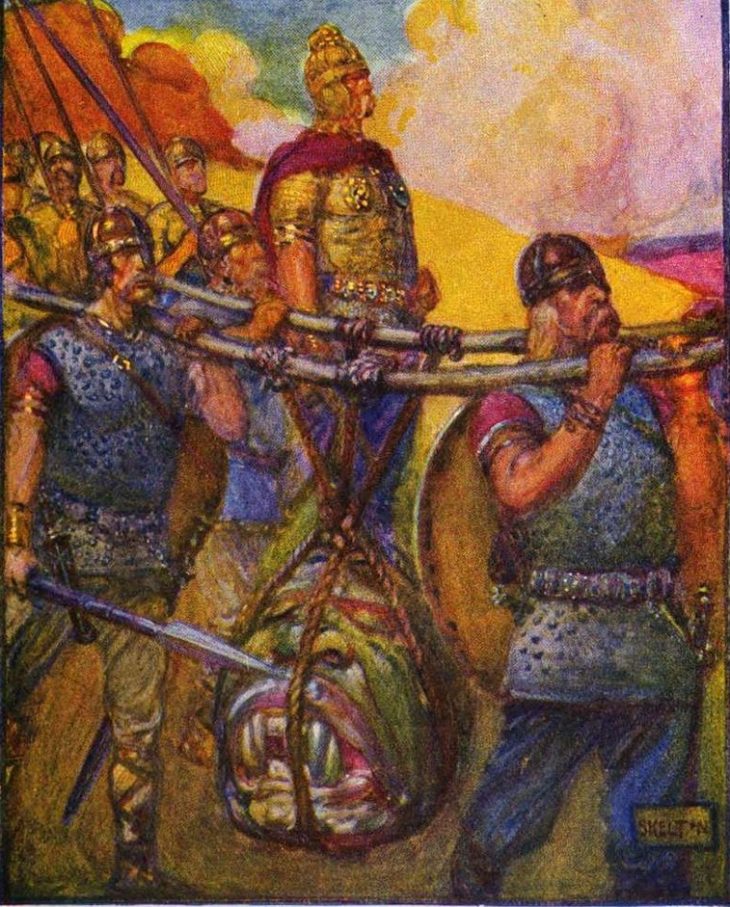

Today’s image is of the Geats carrying the head of Grendel back to Heorot from the mere. It comes from Harriet Elizabeth Marshall’s Beowulf (1908), a retelling targeted toward children. Grendel had a lot of fortitude, but he wasn’t very wise.