Word of the Day: Etymology

Today’s word of the day, courtesy of The New York Times, is etymology, which is also one of the features of this blog. The Times defines it as “a history of a word” or “the study of the sources and development of words” (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/06/learning/word-of-the-day-etymology.html). It gives the pronunciation as \ ˈɛdəˌmɑlədʒi \. Dictionary.com includes “a chronological account of the birth and development of a particular word or element of a word, often delineating its spread from one language to another and its evolving changes in form and meaning” and “the study of historical linguistic change, especially as manifested in individual words” as definitions (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/etymology). It provides this–/ ˌɛt əˈmɒl ə dʒi /–for the pronunciation.

Before we move to the etymology of etymology, let’s talk about the pronunciation. The two suggestions are both just a bit off, in my opinion. The first puts the primary emphasis in the wrong place and closes the first syllable with a d sound. The second has the primary emphasis on the third syllable, which is correct, but it closes the first syllable with a t sound. You might say, “But Dr. Schleifer, the letter in the word is a t, so why shouldn’t it be pronounced as a t?” And my wife would agree with you; she pronounces Doritos with the last syllable being toes. But in medial placements (between two syllables), the sound that is actually pronounced by most people is a voiced alveolar flap: ɾ. The sound is made “with a single contraction of the muscles so that the tongue makes very brief contact” with the alveolar ridge, the part of your mouth just above the upper teeth. It actually sounds like something between a d and a t. So the correct pronunciation would be / ˌɛɾ əˈmɒl ə dʒi /.

The etymology website has a really long entry for etymology. It entered the language toward the end of the 1300s, around the time of Chaucer, spelled “ethimolegia ‘facts of the origin and development of a word,’ from Old French etimologie, ethimologie (14c., Modern French étymologie), from Latin etymologia, from Greek etymologia ‘analysis of a word to find its true origin,’ properly ‘study of the true sense (of a word),’ with -logia ‘study of, a speaking of’ (see -logy) + etymon ‘true sense, original meaning,’ neuter of etymos ‘true, real, actual,’ related to eteos ‘true,’ which perhaps is cognate with Sanskrit satyah, Gothic sunjis, Old English soð ‘true,’ from a PIE *set- ‘be stable.’ Latinized by Cicero as veriloquium” (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=etymology).

The website continues, “By late-14c. a sense had developed meaning ‘the conjugation and categorization of words,’ apparently from a misunderstanding of etymology being the past history of the word to mean that it designates tenses. Often listed along [with] prosody, orthography and syntax as an element of grammar. OED considers this sense to be ‘now historical’” (ibid.).

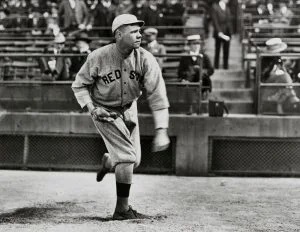

On this date in 1915, Babe Ruth hit his first home run.

George Herman “Babe” Ruth (1895-1948) was the grandson of German immigrants. He was born in Baltimore where his father worked several different jobs before becoming the owner of a saloon. The business kept him very busy, too busy to keep up with young George, and the boy became a bit of a delinquent (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babe_Ruth). At seven, he was sent to a reformatory, St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, where “was mentored by Brother Matthias Boutlier of the Xaverian Brothers, the school’s disciplinarian and a capable baseball player” (ibid.). “Ruth stated, ‘I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball.’”

When he was 19, he signed with the International League’s (a minor league) Baltimore Orioles, perhaps after begin scouted by Jack Dunn, the club’s owner/manager and a former major league player himself. Ruth was signed as a pitcher, and he became a star with the Orioles, but the O’s were a minor league club, and the Federal League (a major league at the time) had established a franchise in Baltimore that year (the Terrapins), and attendance at the Orioles’ games was very low. As a result of the financial problems Dunn faced, he sold his best players, including Ruth, to major league teams, and Ruth’s contract was bought by the Boston Red Sox. He joined Boston midseason, won his first game but lost his second, and was little used after that. Then he was sent to the minor leagues, specifically to Providence.

In 1915, he was again with the major-league club, although the manager didn’t plan to use him much. Injuries and ineffectiveness by some of the Boston pitchers gave him a few opportunities, and one of those opportunities was a start against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Matt Kelly, writing for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, writes, “The game was scoreless and the bases were empty in the top of the third inning when George Herman Ruth stepped up to the plate against Yankee right-hander Jack Warhop. It was only his 18th major league at-bat, and while he had notched three doubles earlier that season, surely few people at the Polo Grounds expected much pop from a hitting pitcher” (https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/inside-pitch/babe-ruth-clubs-first-major-league-homer).

Kelly continues, “But when Warhop wound up and delivered his first offering, Ruth smacked it with a sound that made the 8,000 in attendance gasp.

“‘In the third inning, Ruth knocked the slant out of one of Jack Warhop’s underhanded subterfuges,’ wrote Damon Runyan in the next day’s New York American, ‘and put the baseball in the right field stands for a home run.’

“Ruth’s slam cut through the chilly spring air and landed in the second tier of the Polo Grounds’ right-field grandstands. It was a left-handed swing that the young Ruth would later employ, ironically, to christen the original Yankee Stadium and repeat many times over in the Bronx.

“’Mr. Warhop of the Yankees,’ wrote Wilmot Giffin in the New York Evening Journal, ‘looked reproachfully at the opposing pitcher who was so unclubby as to do a thing like that to one of his own trade. But Ruthless Ruth seemed to think that all was fair in the matter of fattening a batting average’” (ibid.).

Boston continued to use Ruth as a pitcher until 1918, when they began to use Ruth at first base and in the outfield on days when he wasn’t pitching. In 1919, Ruth’s pitching was limited while he played most of his 130 games in the field.

And then he was sold, again for financial reasons, to the New York Yankees. And the rest, as they say, is history, not etymology.

Today’s image is of Babe Ruth pitching for the Boston Red Sox (https://worldhistoryedu.com/babe-ruth-greatest-achievements/). BTW, if you are impressed, as you should be, with the accomplishments of Shohei Ohtani as both a pitcher and hitter, go back and look at Ruth’s entire career.